Dotted along unsuspecting avenues and friendly roads alike are colorful open-air food stalls unlike the sprinkling of restaurants found across Singapore, yet with delectable foods and beverages which attract Singaporeans near and far.

Mamak stalls are unique to the Malaysian peninsula and particularly Singapore, serving a unique blend of Tamil Muslim and Malay cultures. Singapore’s stalls had humble beginnings, dating back to World War II, when Tamil Muslim immigrants set up drink stalls for workers selling teh tarik milk tea outside rubber plantations.

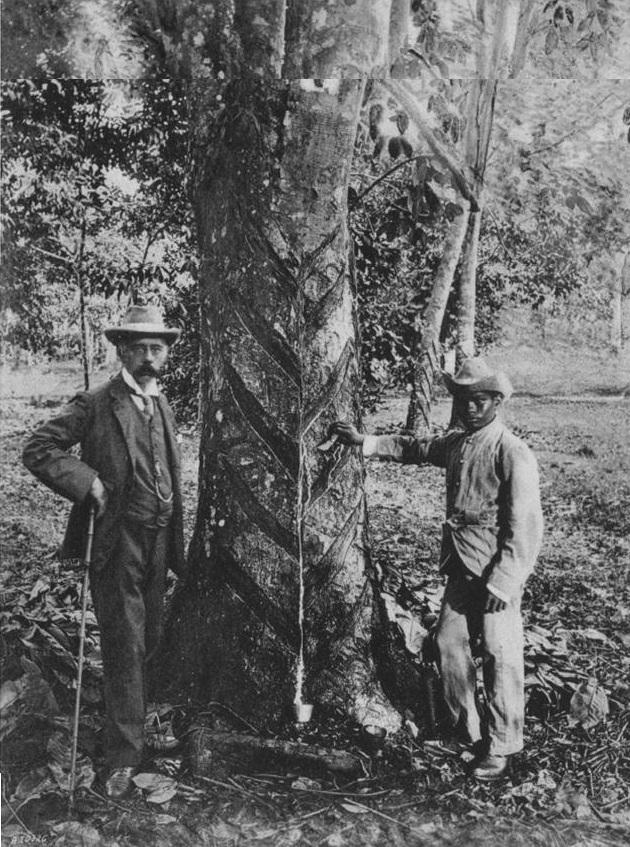

In 1877, 88 years prior to Singapore’s independence, English gardeners sent 22 rubber seedlings to the Malay peninsula with the goal of cultivating plantations and employing local labor. Rubber cultivation was scarce at the time as it was not viewed as profitable compared to cash crops such as black pepper, coffee, and sugar. Along with the advent of the first automobiles, the demand for rubber skyrocketed.

Modern-day Singapore was the hub of the rubber industry in the early 1900s, largely due to Henry Nicholas Ridley, a botanist and rubber researcher who directed operations at the Singapore Botanic Gardens and pioneered a method of rubber harvesting which did not require growers to cut incisions into the tree bark. His work led to a surge in rubber production in and around Singapore which, in turn, created a plethora of jobs and lured workers from across Southeast and South Asia.

With the British Raj in full swing, some Tamils from the Indian state of Tamil Nadu were sent to Singapore to work on these plantations, while others were Indian convicts forced to migrate to assist in the building of early Singaporean infrastructure. The vast majority of Tamil migrants, however, were Muslim merchants who established businesses across the Malay peninsula.

Given the sheer number of workers in Singapore around the rubber plantations, many of these Tamil Muslims decided to set up stalls selling hot street food, coffee, and tea. Originally derived from “mama,” the Tamil term for one’s maternal uncle, the workers began calling these stalls “mamak stalls,” finding in them a sense of comfort and familiarity reminiscent of the families and countries they had left behind.

Teh tarik is itself a Singaporean twist on the masala tea popular in Tamil Nadu. A kopi tiam (coffee shop) staple, teh tarik translates literally to “pulled tea,” owing to the common practice of pouring the substance from glass to glass in extravagant motions in order to blend it and create a characteristic layer of bubbly foam, a spectacle Singaporeans delight in watching as they enjoy their miniature meals.

The tasty tea, made with sugar and fresh condensed milk, is often eaten today at mamak stalls alongside roti prata, a form of flatbread similar to the Malabar parotta. The delicious flatbread is made of fattened dough and oil, kneaded, stretched out, and folded repeatedly to form layers. The dough is then flattened and cooked, sometimes with eggs or chopped vegetables, and served commonly alongside mutton curry or other spicy gravies. Along with teh tarik, the roti prata remains a go-to breakfast food for many Singaporeans today.

Since the colonial era, mamak stalls have grown to serve a variety of snacks and drinks, including goreng (fried), rice and soup dishes as well as traditional Tamil dishes like the dosai and powdered beverage mixes like Milo and Horlicks. The murtabak, a pan-fried variety of folded bread stuffed with scrambled eggs, chives, scallions, leeks, and minced meat, is also a common mamak stall offering.

In some neighborhoods, the roti prata can also be found stuffed with cheese, bananas, or even chocolate with the spin-off “Nutella roti” redolent of the chocolate crepes of France. Maggi Goreng, meanwhile, consists of stir-fried Maggi instant noodles with chilli powder, vegetables, and eggs. And while larger tourist populations visiting Singapore in recent years have motivated some mamak stall owners to upgrade their establishments to indoor, canteen-like eateries, the majority of these Singaporean greasy spoons remain street-side stalls, elegant in their evergreen simplicity.

Mamak stalls remain incredibly popular throughout Singapore due to their fresh, hot food and inexpensive prices, and constitute part of the Lion City’s rich culinary heritage. Despite their similarities, no two mamak stalls are quite the same, with each preparing their teas and foods in a different manner. Many Singaporeans cherish the local stalls they frequent for a quick glass of tea while some university students, mostly on the west side, travel across the island for a good meal at their mamak stalls of choice. Unsurprisingly, Little India has the densest concentration of mamak stalls in Singapore. The residential town of Serangoon, settled by Tamil Muslim traders in the nineteenth century, has a number of mamak stalls as well.

These stalls aren’t just haphazard points on a map one can purchase a fast meal from. Rather, they symbolize the beauty of the human spirit – of the culinary synergy between Tamil Muslims and Malays, of the historical solidarity between workers oppressed by colonial powers and of the strength of the Singaporean people. Mamak stalls are, in the most lucid terms, the pride of the Lion City.

Other stories:

No Baby in the Corner: Singaporean woman makes name in Latin dance world

Uncovering some of the oldest Chinese temples built in Singapore’s early, tumultuous years