Many have claimed that Singapore hides behind a veil of illusionary perfection. For all the light that the country shines upon the world with its justifiably impressive modern-day achievements, there is a soul-consuming darkness that the city-state keeps obscured within the cold, concrete walls of its prisons.

Singapore’s continued practice of the death penalty in the 21st century is an open secret, one that has sparked years of controversy and impassioned debates — especially so in the aftermath of Boo Junfeng’s subtly brilliant film Apprentice. If you’ve felt lost amidst all the noise of conflicting opinions, this will help you better understand the place – or perhaps misplacement – of Singapore’s mandatory capital punishment in this day and age.

Where does Singapore stand on the death penalty?

Despite intervention by the United Nations to abolish capital punishment worldwide, Singapore continues to be one of five industrialised countries – the other democratic states being America, Japan, Taiwan and St Kitts & Nevis – that upholds it.

The iron-willed government of the Lion City has established time and time again that the death penalty has been instrumental in deterring drug traffickers from entering the country. Be that as it may, the statistics are staggering.

Effective? Probably. The fear of the noose combined with a comprehensive national strategy (through education, campaigns and rehabilitiation) has created an environment with one of the lowest prevalence of drug abuse worldwide.

Since 1991, Singapore has hanged over 400 prisoners – of which a significant number constitutes foreign nationals – and arguably topped the list of the world’s highest execution rate per capita in the late 1990s.

When does the law impose the death penalty?

According to the Central Narcotics Bureau, the illegal trafficking of the drugs stated below will result in the imposition of the mandatory capital punishment:

- Cannabis (more than 500 grams)

- Cocaine (more than 30 grams)

- Heroin (more than 15 grams)

- Methamphetamine (more than 250 grams)

Those involved in the manufacturing, possession or custody or under their control (like having keys to a meth lab) will also be liable for the death penalty.

Though 70 percent of hangings are for drug-related offences, other crimes that call for the execution include:

- Waging or attempting to wage war or abetting the waging of war against the Government

- Offences against the President’s person

- Piracy that endangers life

- Perjury that results in the execution of an innocent person

- Murder

- Abetting the suicide of a person under the age of 18 or an “insane” person

- Attempted murder by a prisoner serving a life sentence

- Kidnapping or abducting in order to murder

- Robbery committed by five or more people that results in the death of a person

- Using or attempting to use arms to commit scheduled offences like unlawful assembly; rioting; certain offences against the person; abduction or kidnapping; extortion; burglary; robbery; preventing or resisting arrest; vandalism; mischief.

When do executions take place in Singapore?

Executions in Singapore are traditionally carried out at 6am on Fridays, ironically when most are rejoicing, knowing the long-awaited weekend is almost within reach. Just as people are stirring under toasty blankets and rubbing the sleepiness from their eyes, an inmate on death row is being escorted from his or her cell to the execution chamber.

How are executions carried out in Singapore?

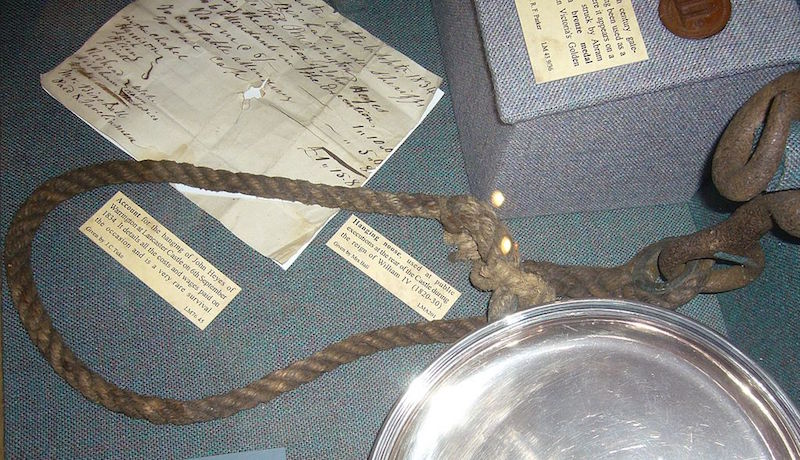

They are done by a hangman, whose identity is kept secret by the state. Based on the prisoner’s height and weight, a noose of appropriate measurements is carefully prepared. The length of rope cannot be too short because the inmate will likely struggle and suffocate to death; it also cannot be too long because that results in instant decapitation.

The noose is placed over the prisoner’s head with the knot strategically slipped right behind the ear. This ensures that the neck – and by extension, the spinal cord – snaps from the impact of the long drop through the trapdoor. The process is quick and humane, and the only people who are allowed to witness it are the doctors and prison officers. The doctor will determine the cause of death and pronounce the time of death.

The last meal

On the eve of their execution, inmates on death row are treated to a special supper of their choice, under the condition that the meal is within the prison budget. The “classiest” option would be a simple glass of milk, which, unlike other food items that may burst out of a person’s body during the execution, stays within the stomach.

The execution of Kho Jabing

Of recent years, no inmate on death row has captured the attention of the nation quite like Kho Jabing. The 30-year-old Sarawakian was first convicted in 2008 after beating 40-year-old construction worker Cao Ruyin to death with a tree branch in a fatal robbery attempt.

Over the years, Kho rose in recognition with each failed attempt at applying for a re-sentence. Initially sentenced to death in 2010, he was spared the noose in 2013, when he was re-sentenced to a life’s term in jail. An appeal by prosecutors, however, re-instated his death sentence — a judgement that has failed to be overturned, despite repeated efforts to fight it.

Much to the dismay of his mother and sister, the Court of Appeal dismissed his appeal on Friday morning, and Kho was hanged later that afternoon on May 20, 2016. His execution eternally established in Singapore’s history as the first to not take place at dawn on Friday.

We Believe in Second Chances

Is capital punishment truly compatible with life in the 21st century? Human rights activists Damien Chng, Priscilla Chia and Kirsten Han – also the founding members of We Believe in Second Chances – do not think it is.

Alongside the Singapore Anti-Death Penalty Campaign, they worked tirelessly to save Kho from the unforgiving machinations of the death penalty, but failed in the end.

“I personally travelled with Jabing’s mother and sister to Kuala Lumpur and Sarawak to hold press conferences that would help raise awareness of his case in his home country,” Han shared.

“We were also present at a round table of Parliamentarians for Global Action to address Jabing’s case to Malaysian MPs. Damien and Priscilla are both legally trained, so they were also able to assist with things like legal research.”

The trio first came together in 2010 to campaign for the life of Yong Vui Kong, a young Malaysian drug mule who was given the death sentence in 2007 for trafficking over 15 grams of heroin into Singapore. Thanks to revisions in the death penalty, he was later given the life sentence in 2013.

“We were drawn to his case because of our proximity in ages. It seemed very inconsistent that our mistakes were being forgiven because we were seen as young, immature and still learning, whereas Vui Kong was expected to pay for his mistake with his life,” said Han.

They stand by their belief that laws and procedures need to be debated and revised because “the death penalty is an irreversible punishment at the end of a process that is prone to human error, which means that it is all too possible that innocent lives will be taken away. And that is something that should not be allowed to happen.”

A foundation built on hanged men

There’s always that one-percent chance of making a mistake in matters concerning life and death, but it’s one that the Singapore legal system is all too confident of not making. Reports of hanged criminals barely get mentions in mainstream media — only high-profile cases get the attention. Even so, it’s only because of prominent voices from groups such as We Believe in Second Chances that pushed them to the foreground of nationwide consciousness. Kho is just one of the hundreds who ended up on the wrong side of the death penalty, and he will hardly be the last for years to come.

Sure, we’ve benefited from Singapore having some of the lowest crime rates in the world, but at what cost? It’s a modern, crucial quandary to reflect on when a safe and secure society is built on the foundations of hanged men.

Reporting by Arman Shah; editing by Ilyas Sholihyn and Benita Lee