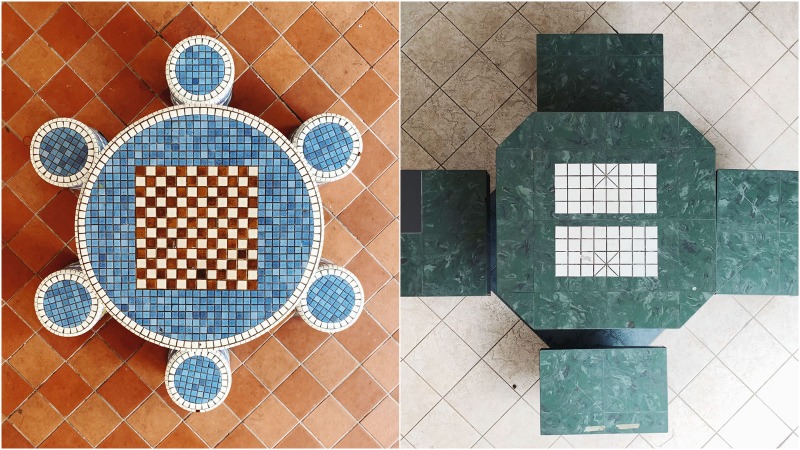

One man has painstakingly collected images of Singapore’s quaint communal chess and checker tables that embellish the city’s decades-old housing blocks.

These solid blocks of concrete, usually decked out in multicolored tiles or marble, have served as gathering points for residents to bond over games of chess and checkers, or simply to hang out for the past 40 years or so.

But they are no longer mainstays of public housing construction, which today is more likely to feature a solitary bench or two at the void decks of blocks built in recent years.

“Taking these photos and sharing them online, I guess it’s a way of really bringing attention to all these small little things around Singapore that you’d probably miss out in your everyday life,” photographer Jonathan Tan, 32, said.

For six months, the creator of the Lepak Downstairs photo project has been photographing the neighborhood meeting places as keepsakes. Lepak means to hang out in Malay.

“Even if the old blocks are there they would go through renovation and all these like features will just gradually disappear. So it’s just quite nice to just put them in photo and memory,” Tan added. When he’s not documenting the community’s built environment, Tan works as a brand manager.

He has so far published images of 18 old-school tables and stools from older housing estates in Telok Blangah, Bedok, and Dakota. There is no official record of how many such installations were built or remain in the country, but they have been around since the late ‘70s.

By 1989, 80% of Singapore’s nearly 3 million population were living in public housing flats instead of shophouses or wooden homes, according to 1992’s The Singapore Experience in Public Housing, authored by former parliamentarian Augustine Tan and former urban development board member Phang Sock-Yong.

Tan himself spent the bulk of his childhood hanging out or waiting for the school bus at the void decks. Recently, he realized that the once-common sight of their concrete tables and stools was fading and would be wiped out by Singapore’s rapid housing development.

“I think that at the core of it, a lot of people acknowledge that all these old school things are really starting to disappear and we need to do more things to appreciate them whether it is taking photos, visiting them or talking about it,” he said. “I think people really want to appreciate and hold on to one of these kinds of past memories.”

He previously published a series on the unique architectural portals of some public housing blocks. Like the tables, the sometimes oddly shaped features were common in the void decks of older housing estates, where they provided air flow and light within decorative frames.

Public and communal spaces have shrunk in societies around the world since their post-war peak.

Neighborhoods in Tampines, Punggol and Jurong West have been rebuilt with newer public estates that include much smaller void decks and lift lobbies. Communal tables have become rare and those that exist aren’t as vibrant as those in the past – and are unlikely to accommodate a chess match. Recreational amenities have mostly been reduced to outdoor playgrounds or rooftop gardens.

According to the housing board, more than 73,000 housing units were under construction in March 2020, a 5.9% increase from a year prior.

New kid on the block

Tan scoured one estate at a time with his phone and selfie stick, which could double as a walking stick after he’s blown out his feet on long walks searching for subjects. The project has turned out to be more arduous than expected, requiring great stamina – and luck.

He once walked around Woodlands for several hours only to find nothing. He had better luck in Yishun, where some blocks even had two sets of old tables and stools near to each other. There is usually at least one in each estate scattered around haphazardly, he said.

“I tried to see whether there was a pattern to know if estates of a certain age or era would have these kinds of tables but it was quite random,” he said. He usually spends half a day searching for these tables and stools before he’s worn out.

“I definitely think one day wouldn’t even be able to cover estates like Tampines so maybe for example, I will spend half a day walking as far as I can from the MRT station and see what comes up from there. I probably cannot walk for a whole day anyway it’s too tiring,” he said. More than 200,000 Singaporeans live in public housing flats in Tampines, according to the Housing Development Board.

In response to requests from his over 3,000 followers, Tan makes sure to provide details of the locations of what he finds.

“A lot of people also messaged me to ask like, ‘Oh where do you find this? I want to do my wedding shoot over there’ but I can’t remember exactly where it is. So this recent series I did make a point to note down everything,” he added. He is also thinking of mapping them out on a proper digital platform or collating them in a book or magazine.

He is eyeing Pasir Ris, Jurong and back at Woodlands next. As of now, Tan’s hunting mission is on hold due to work obligations.

“I’ll definitely want to explore more neighborhoods to find all these different things, because I only covered a fraction of Singapore. It’ll be quite cool to just continue the series, on my own free time,” he said.

Other stories you should check out:

10 things about the filmmaker who gave Singapore the Wes Anderson touch

Singapore’s beloved Dakota Crescent estate finally reduced to rubble

Uncovering some of the oldest Chinese temples built in Singapore’s early, tumultuous years