Although the results are still incomplete and unofficial, former senator and dictator’s son Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. appears to have won Monday’s presidential election with just over 58% of the vote. But many people still have serious questions about how the election was conducted due to widespread reports of malfunctioning vote-counting machines, accusations of harassment and vote-buying at polling stations, and excessively long queues that saw voters waiting between three to 24 hours to cast their ballots, even as election returns were already being broadcast in the media.

Striving to keep the peace and ensure fairness at the polls were an army of poll watchers, many of whom experienced the irregularities unfold as increasingly irate voters began to lash out at electoral board officials.

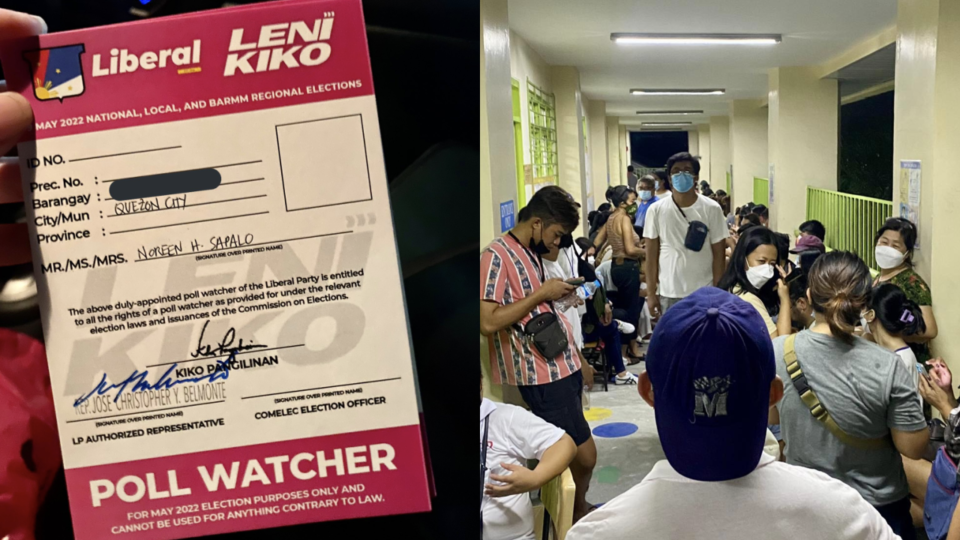

One of those poll watchers was Neen Sapalo, who teaches anthropology at the University of the Philippines. Sapalo tells Coconuts that she had not intended to be a poll watcher on election day, but allegations of election fraud on social media and reports that those manning the polls needed backup made her decide to sign up on election day itself. She volunteered on behalf of vice president and presidential candidate Leni Robredo’s campaign to relieve another volunteer who had been monitoring a polling site throughout the day.

“I wanted to protect the ballots of my kababayans (fellowmen). As an anthropologist, I also wanted to observe the voting process in our local precincts,” Sapalo said.

Despite the fact that voting should have started at 6am and ended at 7pm, Sapalo was assigned to a polling station that same night in Quezon City. There, she says she witnessed weary voters getting irate with electoral board inspectors — most of them public school teachers who had volunteered to work at the elections.

“I found many voters still in line, tired and hungry, but also angry at the (electoral board inspectors) and volunteers. Apparently they had been there since early morning but they couldn’t vote because the SD card of the vote-counting machine wasn’t working, so they had to wait for Comelec to send a new one. The voters and teachers were getting heated with one another,” she shares.

Ultimately, voters who had stayed the night, withstanding hunger and fatigue, were able to cast their ballots at 7am when the backup machine had arrived. “That’s how long they waited just to be able to vote,” Sapalo said.

Across the country, faulty vote-counting machines (VCMs) plagued polling stations — severely delaying already long queues, potentially affecting up to 1 million voters. Election watchdog Kontra Daya (Combat Cheating) said that the breakdown of vote-counting machines this year was much worse compared to the 2019 and 2016 elections at 1,800 versus 961 and 801, respectively.

Amid the widespread reports of malfunctioning VCMs, the Commission on Elections floated a suggestion that affected voters could sign a waiver and leave their ballots with electoral board members, who would feed the ballots into the machines in their absence.

Yet this would mean waiving voters’ right to view the voting receipt that would confirm their votes and leave their ballots open to potential tampering — compelling the most determined of voters to stay behind and wait until working machines had arrived.

“Of course, not everyone who originally fell in line were able to vote — they had gone home that night because they were frustrated, tired, or hungry. That’s disenfranchisement! They were robbed of their right to vote,” Sapalo lamented.

Sapalo believes that the Commission on Elections (Comelec) was ultimately responsible for the chaos.

“(Comelec) failed to ensure that the vote counting machines were in good condition. They did not train the BEIs and teachers well — that’s why the teachers were having a hard time explaining the process to voters — and they did not effectively inform the public of the voting processes.”

Instead of purchasing new machines for this year’s elections, the Comelec awarded a PHP637-million contract (US$12.09 million) to refurbish old Smartmatic machines that were used in the 2010 and 2016 presidential elections, while decreasing the number of backup machines to 2,000 this year, compared to 7,000 in 2019.

Sapalo also shared that the inspectors received little information about the contested waivers that relinquished voters’ right to feed their ballots into the machines themselves.

Reports of delayed voting were rife as some voters questioned the validity of the electoral process, especially considering that a partial electoral count was already being broadcast that same night that poll watchers like Sapalo were still tending to voters unable to cast their ballots in the precincts.

In Sapalo’s view, it’s not wrong that Monday’s election left doubts in many people’s minds. “This is definitely a fair observation based on evidence and facts. There are a lot of ‘receipts’ on these anomalies and irregularities. Comelec should have ensured a smooth voting process to avoid distrust.”

Sapalo also believes that Comelec should have waited for every vote to be accounted for before beginning the transmission of votes. “So many accounts of irregularities were reported. In fact, this year’s elections recorded the most number of VCM breakdowns. This is contrary to Comelec’s statement that this election was successful. Is it not a failure of elections if there are many faulty VCMs and thousands of people were not able to vote? The transmission of votes to Comelec’s central office is also dubious amid so many reports of faulty systems.”

Ultimately, Sapalo believes that the Philippines’ faulty electoral system is symptomatic of a fractured democratic process. “At this point, we should know that voter education alone isn’t going to solve our pre-election woes. We need to understand that there are minimum prerequisites we must meet before the general public can appreciate this: There must be a functionally and politically literate public, an electorate that values truth and science and that can distinguish facts from lies despite the prevalence of disinformation.”

“Fact-checking, as important as it is, is not enough. It’s obviously not just a battle of truth versus lies anymore. We have since moved on to a greater challenge: convincing them why the truth matters. And then there’s the need to understand what the national and local elections mean to the great majority of the nation, to understand their ‘local moral worlds.’”

Beyond the still pressing questions about how this election was conducted, the anthropology teacher said there are bigger, more existential questions about democracy in the Philippines that also require serious inquiry.

“Every election time, what matters to [voters]? Do they view voting as a civic duty? How do they view politics beyond elections? These questions are important because the center of every election is the community. And their experiences of structural and slow violence, of injustices, should always inform our thinking and doing. Otherwise, we all lose.”