In the pre-dawn hours of September 24, 1974, the people of Palimbang, a town in Sultan Kudarat, Mindanao, were awakened by the sound of bombs. That was only the beginning of a long ordeal for the thousands of people who lived in the villages of Palimbang.

In the next weeks, in what would become one of the worst state-sponsored atrocities that would be committed during the Martial Law era, a large contingent of military troops would execute nearly all the men of Palimbang—more than a thousand of them, perhaps as many as three thousand. The military men raped women, terrorized and tortured villagers, and leave children to starve to death.

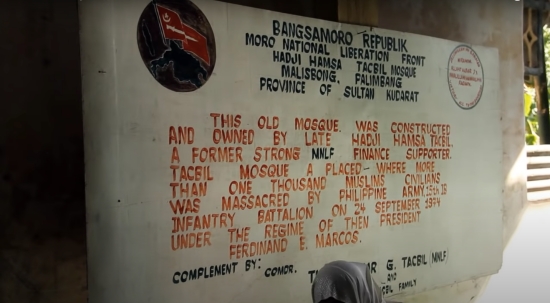

This all happened a few days into Ramadan in 1974, two years into Martial Law, when Mindanao was placed under military rule. The area had seen intense ground fighting between the military and the Moro National Liberation Front, which were backed by air and naval attacks. Driven by intelligence reports that the MNLF were gathering forces near the village of Malisbong—and summoned by Governor Gonzalo Siongco, who was a brigadier general in the army—military forces descended into Palimbang.

When people in the Palimbang’s seaside barangays felt the shelling and bombing, thousands of them fled into the mountains. A few days later, negotiators from the military found the evacuees and led them back down into Malisbong.

According to survivors who are still alive, after a few days of being held in the village, the men were forced into the Tacbil mosque, while thousands of women and children were loaded into a naval boat anchored near shore. Other women stayed in the village but were locked in a warehouse, purportedly for their safety—the army captain wanted to keep them safe from his own men.

Kept on the boat for several days, the captives were exposed to the harsh sun; there were children who died of heatstroke. Their bodies were thrown overboard. Eyewitnesses say that they had overheard military officers saying that the orders were to make sure no one was left alive.

READ: So what was so bad about martial law?

Living memory

There is plenty of documentation of this dark event in living history—including interviews with survivors, recorded for posterity in documentaries like Forbidden Memory by Maguindanaon filmmaker Gutierrez Mangansakan, which was named Best Documentary in the 12th Cinema One Originals film festival.

The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) has also produced a documentary, for which many survivors talked about the horrifying events that led to the deaths of their family members, and about the atrocities they themselves had to endure.

And the stories are horrifying indeed. Hadji Muhammad Faust Piana was already an imam in 1974, and was one of the men rounded up into the mosque. Though he was tortured, he was one of the rare few who were spared, and he witnessed how the others were tied and led out of the mosque—five or ten in a day—to be executed.

Bernie Bandala, who was a young boy at the time, saw soldiers attempting to rape a woman. She committed suicide by plunging a pair of scissors into her neck, he says, and he was among a group of children who used the commotion to escape into the woods.

Amina Gunao describes how her husband was killed before her very eyes after she tried to bring him food while he was held at the mosque. Another woman, Bayol Maguiales, describes how a soldier raped her after she asked for food for her neighbors.

#NeverForget

Though truly horrific, the Palimbang Massacre is not well-known or remembered by many people. In fact, people like Rigoberto Tiglao and Juan Ponce Enrile have publicly denied that any massacre had taken place at all. This, despite the numerous witnesses who lived through the atrocities.

On the 40th anniversary of the massacre, in 2014, then CHR chairperson Etta Rosales went to Malisbong to mark the somber occasion. A Marine officer was also at the event. “Awkward ‘yung presence ko dito eh,” he said. “Kasi uniporme na suot ko ngayon ay suot din na uniporme ng mga gumawa ng massacre noong 1974…Humihingi po ako ng patawad sa mga ginawa ng katulad ko.” (“My presence here is awkward. The uniform I’m wearing now is the same uniform worn by those who committed the massacre here in 1974…I ask forgiveness for the things that were done by those like me.”)

That same year, the Philippine government recognized the thousands killed in Malisbong as victims of martial law human rights abuses. With help from the CHR, families of the victims and other survivors were awarded claims to the P10 billion set aside for the Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013.

Read: Never Forget: Robredo urges Pinoys to reject ‘lies’ on 48th anniversary of martial law