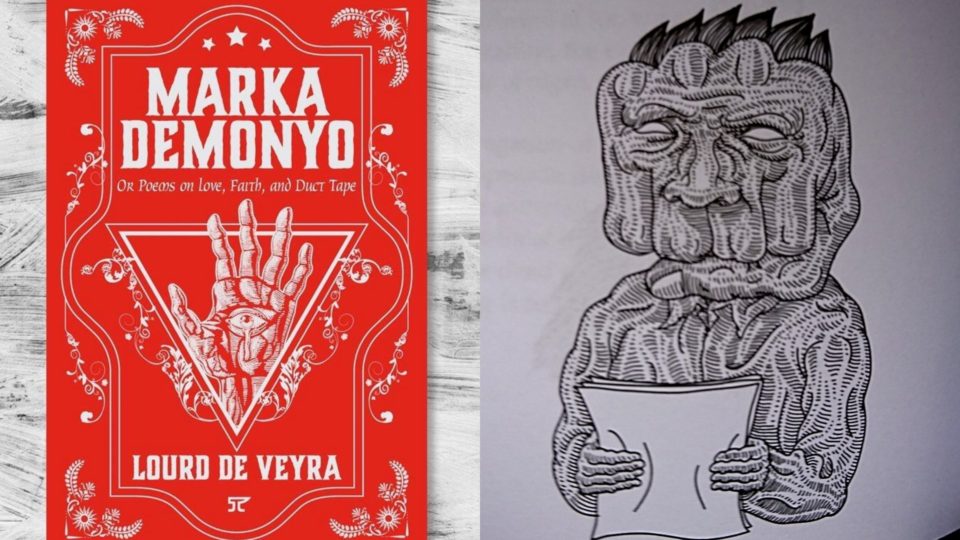

Marka Demonyo (“Demon’s Mark”), a palm-sized book of poems that’s inconspicuously crammed with 46 verses on everything from fisting and silver screen baddies, to Caloocan City druggies and Adobo Jesus may seem like a lot to process. But its author Lourd de Veyra said his new book also kind of looks like your grandma’s daily devotional.

It took more than two decades for de Veyra to become a cult figure of sorts, he’s been a musician, motoring journalist, essayist, novelist, talk show host, and news anchor. But while the Palanca-award-winning writer continues to wear many hats, it looks like “poet” isn’t something he’ll retire just yet.

De Veyra talked to Coconuts Manila over email about writing poems about drug war victims in the religious-looking red book designed by Tom Estrera and illustrated by Paul Eric Roca, which was released by Anvil publishing last month.

But don’t let his fourth collection of poems intimidate.

The TV5 anchor said we’ve been conditioned to treat poetry as a math equation that needs solving, when in fact, poems should be examined for how they make you feel.

Well, here’s to examining those feelings.

Marka Demonyo is probably the least subtle title out of your other poetry books. How does it compare with Shadowboxing, Insectissimo, etc. and is there an interesting story behind the title?

For people of my generation marka demonyo is the gin brand with that infamous label: the charming tableau of St Michael slaying the devil [that was painted by National Artist Fernando Amorsolo]. In some ways, the past few seasons in this country can hardly be described as angelic.

So this is probably my most “political” book, a meditation— to use a painfully pretentious word— on the nature of violence, brutality, especially toward the Other. There are significant images from the drug war— dark, fecal slum alleyways and police precincts smeared with blood, random angels of death on motorcycles, the point of view of the meth head, children watching daily as tattooed corpses are fished out of canals, etc. But there’s also lots of moments of humor, albeit dark humor, but at least it’s still humor. Does that make sense?

Actually, it does. On the cover, it says poems of love, faith, and duct tape. What is duct tape a metaphor for? And/or are there literal poems about duct tape in the book?

Observers of the drug war would recognize swathes of duct tape around corpses, which gives them the appearance of silver zombies. Or gray cocoons. And it amazes me how the packing looks so frighteningly neat and efficient as if they were more like FedEx veterans instead of cold-blooded murderers.

What about love and faith?

The part about “love” and “faith” are obviously sarcastic, and if you’ll notice the size of the book, it’s meant to approximate the dimensions of a handy pocket prayer book. That or the publisher just wants to economize.

How many poems are there in Marka Demonyo and how long have you worked on them?

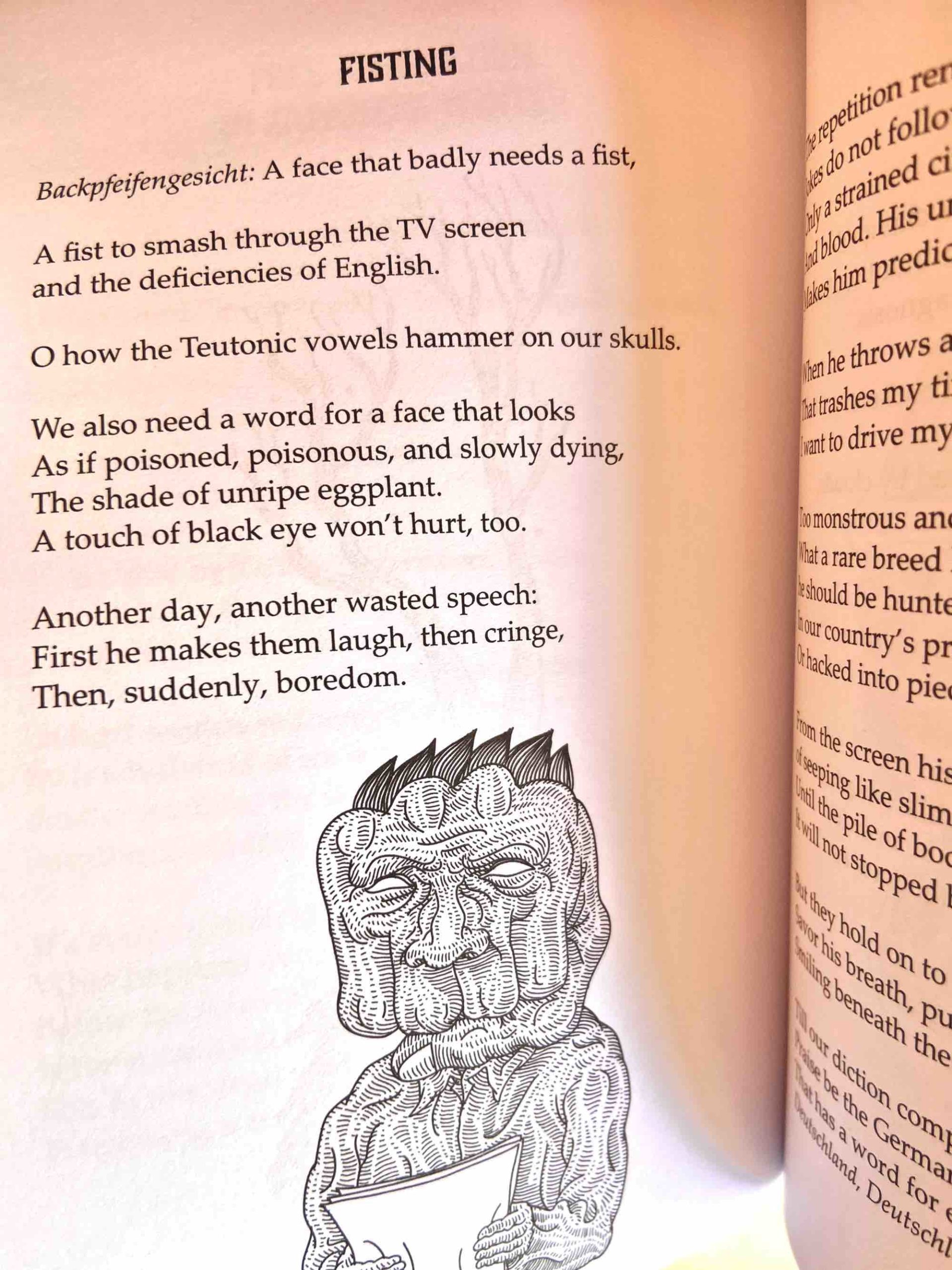

Originally there were 53 or 54. But in a moment of sobriety, after being jolted by the awfulness or the anachronism of some of them I trimmed it down to 46 pieces. When it comes to poetry, I can be a terribly insecure bastard. My last poetry collection Insectissimo was in 2011 and I have written stuff in the last 9 years. But I decided to reserve most of them for another collection. Most of the poems in Marka Demonyo have been written in the last 3 to 4 years as urgent responses to the prevailing gristly narrative. But I’ll tell you this: even if you don’t really care about my verse, Eric Roca’s hauntingly surreal black-and-white illustrations alone are worth the PHP199 (US$4) retail price.

You’ve written for newspapers, magazines, and websites. How does writing poetry compare to doing all of that, and why do you personally feel the need to write poems? Why do you think poetry still matters?

I’m not sure poetry still matters to the world, but it certainly does to that increasingly small sector of humanity who still cares about language and the written word. As corny as it may sound, it’s a matter of survival, particularly that of the mind’s. It’s like true love, as the Polish poet Wislawa Szymborszka once wrote— “Perfectly good children are born without its help.” It’s a rather demanding and harsh muse, especially if your professional life revolves around inane political sound bites. Somebody once said that poetry is language raised to the nth level.

You’ve been doing this for a long time. Do you still feel the need to explain poetry to people who have a hard time understanding it, or find it intimidating?

I guess it’s an issue of conditioning. We’ve all been trained by school teachers to approach poetry like it was some mathematic equation to be solved— detecting the metaphor and other examples of figures of speech, dissecting the damn thing for the meaning as it were a lab frog. Instead of asking what the poem is trying to say, we should first ask, “What did I feel after reading it?” If we were all after the message, a wise man once said, there’s always the post office. It can drain the joy and pleasure out of poetry. It’s not bad per se, but I think what ought to be taught first is how a poem can become a source of delight.

Do you still remember the first poem you wrote? What was it about?

Can’t remember. But I know it’s kadiri [“disgusting”]. Next question, please.

When do you do write most of your work—poetry or otherwise? Do you have a process or routine? How has the pandemic influenced the way you work and write?

I’ve learned to appreciate the value of the iPhone’s Note app— media people have mastered the fine art of hurriedly banging out entire program scripts on mobile phones, as the news crew cab weaves maniacally through EDSA traffic, trying to beat the primetime deadline. I don’t write complete verses on the phone, though, but it’s a really handy tool for jotting down words, fragments, and images that may otherwise become fugitive. I also keep a journal but during the lockdown I just found myself doodling on the pages.

What about the first poem you read that got you really excited? Or something you wished you had written?

Not really a poem, but a song by the punk band The Dead Kennedys called “Kill the Poor,” which taught me satire and how words could approximate the density of nails or blade or acid. Later on, it was encountering T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and Sylvia Plath’s “Edge,” two poems whose meaning I’m still trying to figure out up to now.

Where do you think poetry stands in the realms of Philippine literature? Do you think it’s an underdog compared to novels and long-form fiction? Are there enough Pinoys reading and writing poetry?

Tragically, not enough. But… explain why the bookstores’ literature shelves are groaning under the weight of the Lang Leavs and Rupi Kaurs?

What else are you up to these days?

I’m playing guitar for a noise-metal band named Kapitan Kulam and we were supposed to mix our debut record before the lockdown happened, and during the first few months of the ECQ [enhanced community quarantine], I with a couple of friends recorded an experimental electronica album under the name of Kalayaan Quarantine Orchestra. Though I don’t think we’d be getting invitations to the Wish FM Bus soon.

On a side note, how have you been coping through this pandemic?

I’ve returned to my first obsession— drawing. I’ve been doodling like a maniac these past few months. And I post them on the Instagram account @lourdoodling to address my shameful need for external validation.

Read more Coconuts Manila articles here.