By no means are we against stocking up on sardines and canned goods to get you through the monthlong community quarantine, although you’d have to admit, fruits and vegetables are still the more nutritional option. The problem is, they don’t stay fresh for long—but there’s one way you can extend their shelf life.

“Fermentation cannot be more relevant today,” plant-based cook Mabi David, a self-proclaimed “fermenthusiast” who’s been teaching people how to extend the shelf life of perishables tells Coconuts Manila via email chat. Author of children’s book Paano Kumain ng Kulay? (“How to Eat the Rainbow”) and unorthodox cookbook Makisawsaw (loosely translated as “To Participate”), David, asserts that cooking and making your own food from scratch is “a form of resistance.”

Her pantry is currently stocked with at least six jars of ferments, with flavors ranging from sour, spicy, and salty. She tells us they’re all nourishing, and each with their own different kind of “kick.”

Her first fermentation project was vegan cheese cultured from cashews because as David learned as far back as 2016, not all fermented food is sour.

“I wanted to understand how to draw umami from plant-based sources and my research kept surfacing fermentation as one of the ways,” she said. “I saw that a lot of vegan recipes also relied on traditionally fermented foods such as miso and soy sauce for deeper flavors…I guess bad food craving is the mother of fermentation.”

So, ready to try something new in the kitchen? God knows we’ve got plenty of time. David shared with Coconuts idiot-proof ways to ferment food, the biggest mistakes to avoid when fermenting, routines to keep from losing your head while in isolation, and how food (yes, food!) can be a form of resistance.

Fermentation is such a broad topic. Where does one start?

It is a massive topic given that it’s an ancient preservation technique practiced worldwide. Its tremendous benefits go beyond flavor enhancement, namely extending the shelf life of highly perishable but highly beneficial foods and the enhancement of their nutritional benefits in a manner that is essentially not energy-intensive. I mean, you just chop vegetables, salt them, and wait. And these benefits of fermentation cannot be more relevant today, given the perils of public health emergencies. We have to strengthen our immune system and preserve health-promoting food for times of scarcity.

What would be a gateway food to ferment?

I keep telling everyone who wants to learn that sauerkraut is the best gateway ferment, given how it needs only cabbage and salt.

Which part of fermenting do you focus on and how long have you been teaching it?

I started teaching fermentation in late 2018; I teach it from a cook’s perspective, as a health-promoting, umami-building kitchen skill while saving surplus or perishables from becoming food waste. I just want to clarify that I am a cook and an avid researcher, not a microbiologist or nutritionist. I focus largely on the lacto-fermentation of fruits and vegetables. (Lacto- refers to lactobacillus bacteria, which was first studied in milk, should not be confused with lactose, and does not use dairy.) I also make miso and teach people how to make it.

I didn’t set out to be a fermentation teacher. I would often share my fermentation adventures and what I read on my Instagram account, and people started asking me to hold workshops. I resisted for a while and gave away the information freely because it’s really quite easy. However, I realized people wanted to be guided despite the volume of information available online.

Modern life has tried to scrub and sanitize and sterilize away the world of microorganisms (of bacteria!). But not all bacteria are the same. A lot of bacteria actually protect us, e.g., breaking down nutrients for better absorption or defending our bodies from invading pathogens.

What’s the biggest mistake people who are new to fermenting make?

I’d say the biggest challenge (not necessarily mistake) is usually getting over this fear and bias against microorganisms so that we can reap the benefits of fermentation.

In terms of the actual practice, the most common mistake is under- or over-salting, which can spell success or disaster for your ferment. The second is to keep everything submerged in the brine because lacto-fermentation requires anaerobic environments. I’ve taught a few people who neglect to do this and then get anxious about mold or yeast growth. Keep it submerged.

Is home fermenting meant to be easy? Can anyone do it?

Yes, home fermentation is very easy because (1) it is versatile: you can ferment a lot of produce following general principles; and (2) it requires very little to undertake, you only need the product you will ferment, sea salt (NOT iodized salt which has antibacterial properties), brine or salt and water solution (sometimes), a glass jar with a plastic lid, and weights to keep the ferment submerged.

Do you think fermented food is an acquired taste? Or as Filipinos, do we have more or less the taste buds attuned to it?

Ferments are generally sour, and I’d like to think we are attuned to it given sour flavors and sour cooking are a large part of Filipino cuisine, with our paksiw (fish simmered in vinegar) and sinigang (sour clear broth). [Add the fact that we like] using different souring agents all over the regions and our wide variety of local vinegar.

Have we overlooked local flavorful food that we may not have realized were fermented? Which ones are your favorite?

Our constellation of condiments is traditionally fermented: soy sauce, vinegar, fish sauce, and shrimp/fish paste. Rice cakes such as puto and bibingka were also traditionally fermented.

My father’s side is Kapampangan so I have memories of pindang (fermented carabao meat), burong isda, burong kanin, and mustard leaves, though I no longer eat the animal-based ones. In terms of favorites, I enjoy burong mustasa in fried rice. I love all sorts of vinegars and I am always on the hunt for different kinds. My current favorite is Suka Watwat from the Mountain Province.

How long before people can enjoy their preserves?

For lacto-fermented produce, the process usually takes an active time [the process of making it] of half an hour and waiting time [process of fermenting] of five to seven days. Because this is is a preservation technique you can let the ferment sit in the fridge for as long several months. Some improve with long aging. If I am making a big batch, which I sometimes do with kimchi, it takes me around two days. When I make miso, it also makes sense to make a big batch given the culturing period of at least two months, and it takes me around three days [to prep], which includes growing the starter myself, fermenting then cooking the beans, then making the miso.

What fermented foods are in your pantry so far, maybe ideas we can borrow?

Oh, boy. Here’s a list of what I have in my pantry:

- Three kinds of vinegar that I am still aging – pineapple, guyabano and Indian mango, and various vinegar mothers [which are cloudy, web-like sediments]

- Four kinds of miso – white bean, black bean, soybean miso, red bean miso, which are all local beans from Good Food Community

- Four kinds of kraut: plain cabbage, cabbage and caraway, curried carrot, and lemon rosemary sauerkraut

- Two kinds of kimchi: baechu (red) and white kimchi

- Three kinds of preserved citruses: preserved Tublay lemons, preserved calamansi, and preserved calamansi in Indian spices

- Fermented scotch bonnet hot sauce (1.5 years old)

My ferments are a lifesaver. I’ve had days when I didn’t have any fresh produce, but I was still able to eat healthy because there was kimchi to go with the rice, sauerkraut I turned into soup, and so on.

What’s your routine like during the lockdown? How do you keep from losing your head?

I find that I’ve been waking up earlier than usual. Roughly my routine is: drink coffee, read the news online, have breakfast, assess the produce/ingredients situation and plan my cooking around it, i.e., cook healthy plant-based dishes out of what’s available for delivery to family and friends who need/request it, and ferment those that I cannot immediately deal with to prolong their shelf life.

I create content and test plant-based recipes and the visual tutorials on fermentation, since the response has been really positive and people who haven’t fermented anything have started doing so and would send me pics of their krauts. I check messaging apps to check up on family and friends, then work on the fundraising campaigns I am involved in, among them Lingap Maralita, to support the ones who are among the most neglected in this lockdown, such our farmers and the urban poor.

Every day I have a 16-hour period of fasting in solidarity with those who are hungry and to remind me of my own privilege in these times. When there’s time I watch a Netflix series and read a book. At the end of the day, I am tired and have no problem sleeping and very little energy for despair. For better or for worse, I find that action, purposeful action, can be an antidote to despair.

What do you think quarantine time is doing with our relationship with food?

We need to learn how to feed ourselves both personally and as a society—to cook, grow our own food, see ourselves in solidarity with our food security frontliners—because it is essential to our survival, and it took this pandemic to truly drive home that lesson. It puts a clearer focus on the alarming consequences of when we are disconnected from the people who grow our food.

This time of quarantine and the challenges it poses on our food system shows us what [American] farmer and environmental activist Wendell Berry has long told us, that the act of eating is an agricultural act. And therefore whenever we eat, we are participating in the creation of a food system. The farmer and the eater are interdependent, and we are not just consumers at the end of a long food chain. Rather, we are co-producers of the food system and we can shape it into one that is nourishing, just, and sustainable.

Fermentation has a lot to teach us on this. This time-honored skill provides us with the ability to prolong the shelf life of food, improve flavors, and promote health—important aspects of nourishment, especially critical in these times, that we have outsourced to big corporations, while we wait at the end of the food chain for processed fortified foodstuffs on supermarket shelves.

What will happen to our bodies, our health, if we eat all those ultra-processed foods day in and day out? Rows upon rows of products… are ultra-processed variations of wheat, soy, corn, and rice and then jacked up with too much salt, sugar, and hydrogenated oils.

I am not against modern conveniences, don’t get me wrong. I am saying that we are not passive constituent parts of food production. We are active members that can shape it to make sure everyone and I mean everyone, is fed well and with safe, healthy, and affordable food. But we need to participate in its creation and to reclaim the interdependence of farmers and consumers.

_____________________________________________________________

PIN IT! Principles for dry-method fermenting, according to David

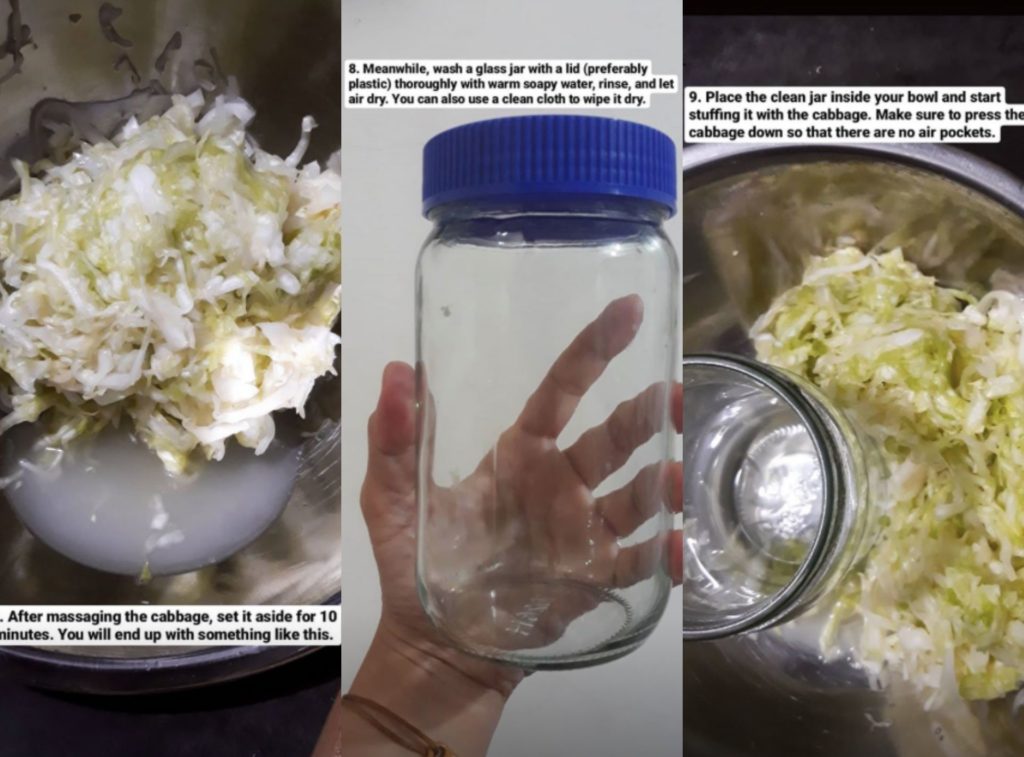

Ready your vessel of choice

Wash your jar and lid with soap and warm water then let air dry.

Prep your produce

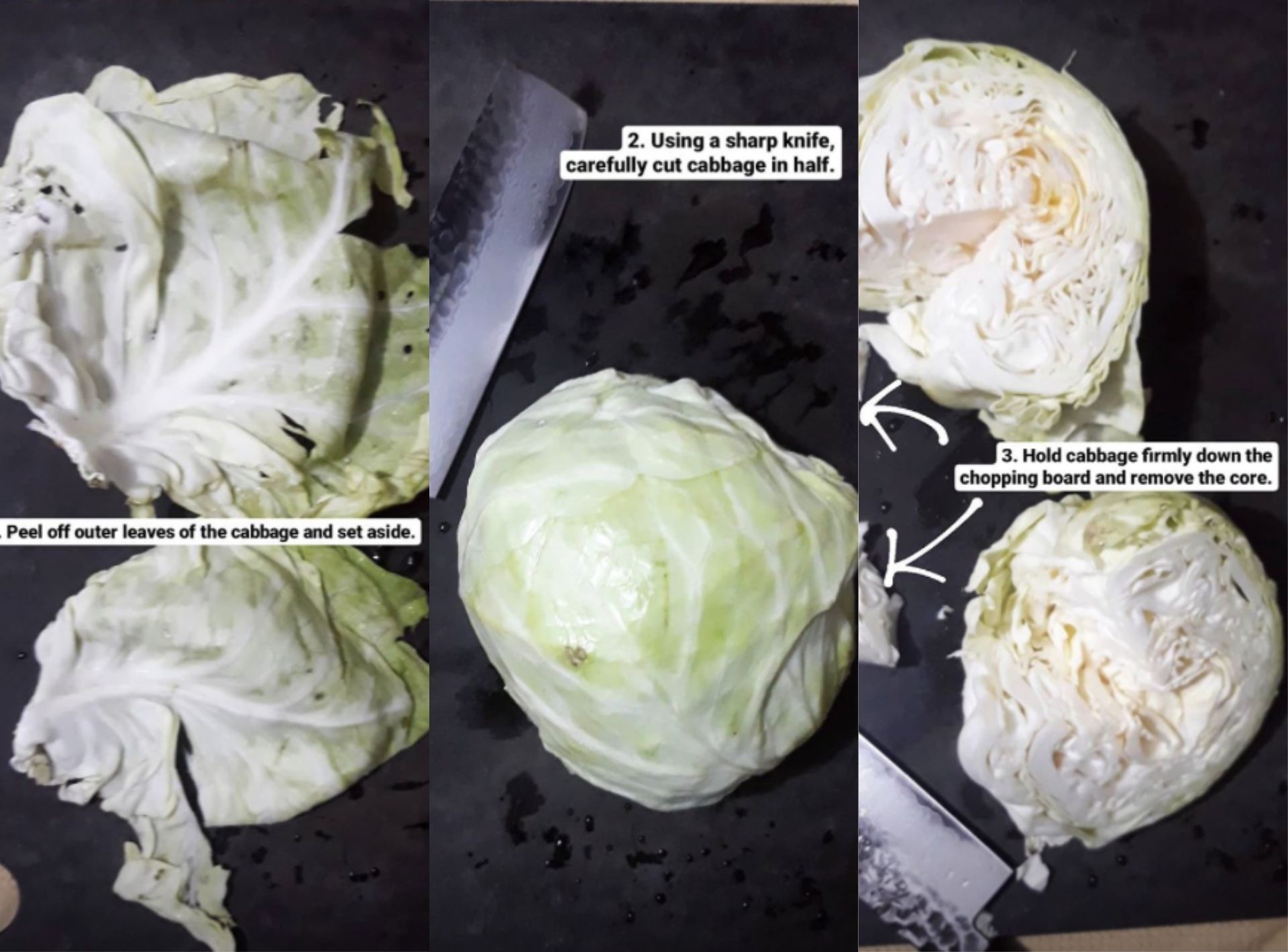

- Wash vegetables thoroughly. Peel and deseed if needed. Remove the core or vegetable butts if applicable and set them aside, and any outer leaves that look the worse for wear.

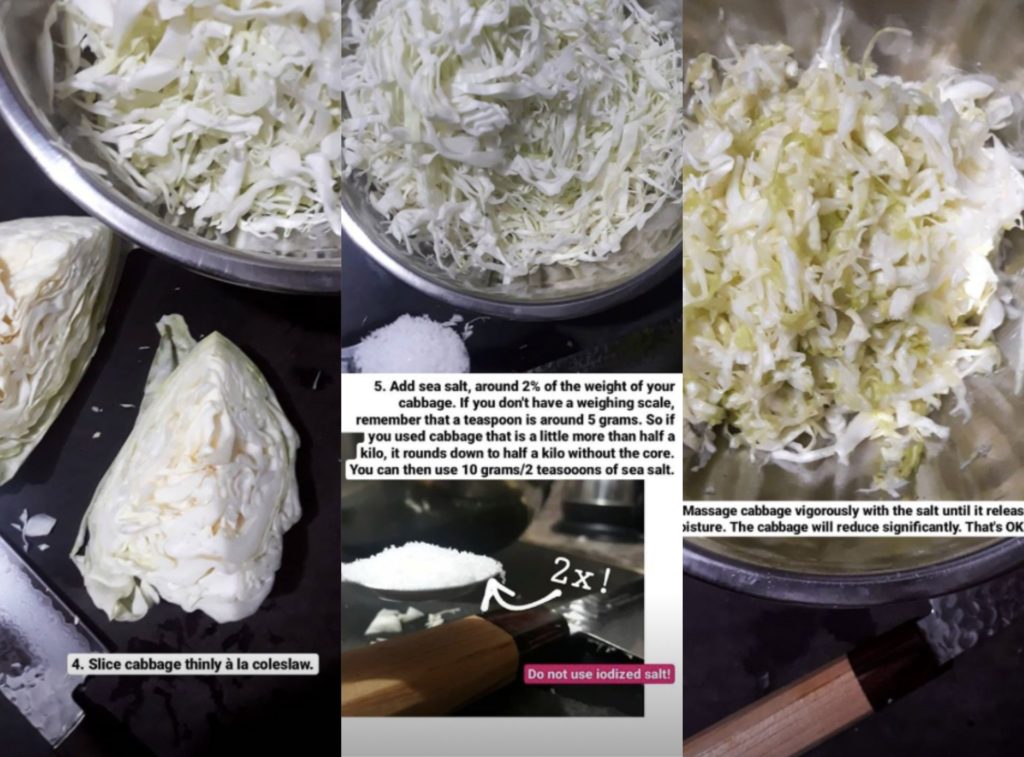

- Cut your vegetables. You can slice them thinly or chop them into chunks. Know that the length of time it takes them to ferment and take on a sour flavor depends on their size (apart from ambient temperature) so smaller cuts ferment faster.

- Place your chopped produce in a large non-reactive mixing bowl and add salt. Your salt needs to be 2% of the total weight of your produce.

Use salt calculatingly

- The right amount of salt is important because it creates a hospitable environment for the lactobacilli, which we need while killing other unwelcome bacteria; and seizes the pectins in the produce, ensuring they stay crunchy throughout.

- This is where a weighing scale comes in handy so you take away all the guesswork and the anxiety over whether or not you salted your ferment properly, and minimize the risk of food waste. If you don’t have a weighing scale, just remember that half a kilo of produce needs two teaspoons (10 grams) of sea salt. If you plan on fermenting regularly, invest in a kitchen scale.

How to stuff veg in a jar

- Massage your produce vigorously until it releases moisture. Set aside for 10 minutes and let it sweat some more.

- Pack massaged produce tightly into your jar. Press down if needed for the brine to rise. Feel free to add the brine that is in your bowl.

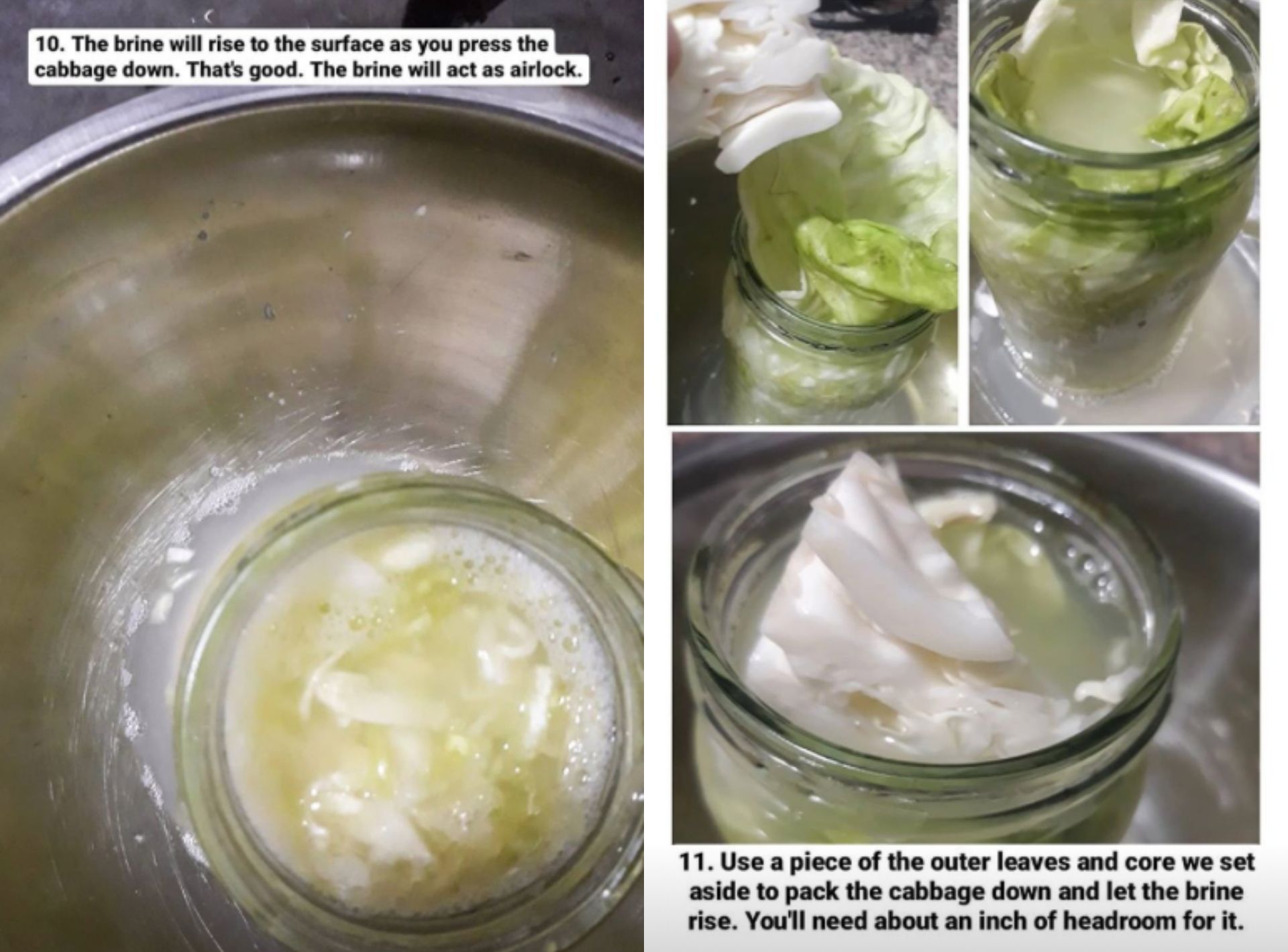

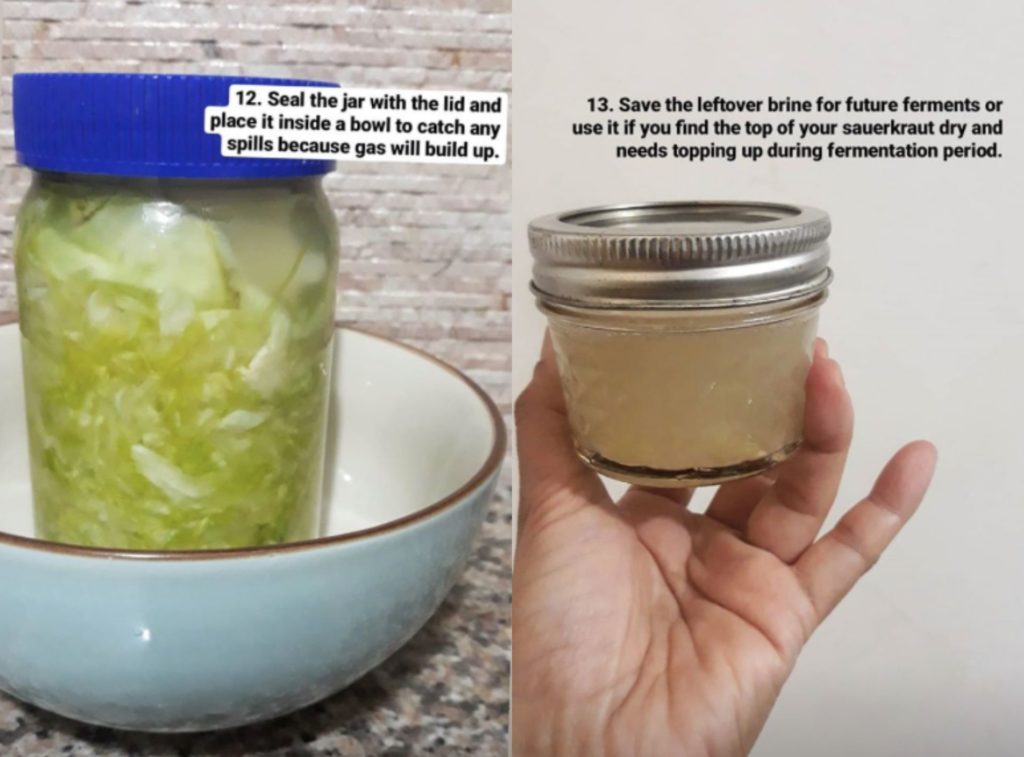

- Add weights (make sure it’s clean and sanitized) to keep your ferment submerged. It can be as simple as beans or water poured inside a clean jar or plastic/Ziploc bag and inserted into the jar, provided they won’t get stuck inside the bigger jar. Sometimes I use layers of vegetable cores or butts, that’s why we save them in step 2. Cover with a lid.

- Set your jar on the counter and let it ferment for five to seven days. If you’re using a tight lid, best to burp your ferment daily by twisting the lid open to release the gas buildup. Check daily to make sure the produce remains submerged. Taste daily after day three and move to cold storage when the sourness is to your liking.