With the release of the trailer for Filipino fantasy series Bagani last week, social media was once again abuzz with conversations about skin color in Philippine entertainment.

Having been touted as taking place in a pre-colonial setting, you could forgive Filipinos for thinking that Bagani‘s cast wouldn’t look quite so — European.

Amid the resulting uproar over the largely mestizo (mixed-race) cast, one writer from the show stepped up to explain that it wasn’t a “pre-colonial” setting at all, but rather a mythological world.

That might explain why a bunch of ancient Filipinos would be half white, but it did considerably less to explain why they’d be dark-skinned but played by mestizo actors covered in bronzer.

If any of this is coming as a shock, you don’t know much about Filipino television.

PhD scholar E.J.R. David, author of Brown Skin, White Minds, pointed out the painfully obvious issues with the casting decision last week in a chat with Coconuts Manila.

“[It’s] problematic because there is an abundance of talented and naturally brown-skinned actors in the Philippines,” he said.

“So to finally have major lead roles for brown-skinned characters, which is rare, and yet have naturally brown-skinned actors passed over for those roles … It simply reinforces the light-skin bias in society and does nothing to empower and lift up brown-skinned actors – and brown-skinned Filipinos more generally.”

Brown-skinned Filipinos, of course, represent the country’s overwhelming majority. According to the latest National Geographic genome study, the average Filipino has less than five percent European ancestry, and if you’ve spent more than a few minutes on the streets of Manila, that percentage will instinctively feel about right.

But turn on your TV, and those percentages can feel suddenly flipped on their head.

To say mestizo actors dominate prime time would be a ludicrous understatement.

We’re talking about an industry in which a drama series that aired this decade — Nita Negrita — featured a half-black Filipino character played by a light-skinned actress with a makeup job that would have made Al Jolson proud.

While there have been successful darker-skinned actors, they have always been an inexplicable minority. Or maybe it is explicable.

“Media — film and television and magazines — have a huge role in perpetuating the idea that lighter skin is more desirable than dark skin,” David said. “Right from the get-go, from childhood, Filipinos are already bombarded and inculcated with these ideas.”

That’s not a concept you need to explain to Chai Fonacier. Those deeply skewed standards of beauty — ones that Filipino children are being exposed to in primary school textbooks — are ones the up-and-coming indie film actress has been confronted with her entire life.

“There is messaging around me that makes me frustrated or paranoid about what the future will hold,” the Patay Na si Hesus star said, referencing huge billboards along Manila’s major highways and commercials featuring white-skinned Filipinas being marketed as “Kutis Pinay” (Filipina skin) and “Kutis Artista” (Celebrity skin).

“I saw these billboards before I became an actor, and it had already made me upset seeing them,” she said. “Even more now that I’m an actor. When you’re surrounded by these images … it can get to you sometimes.”

Longtime director and casting consultant Jade Castro has his own criteria when trying to match actors for roles, a checklist he said rarely includes color. But when it comes to casting the leads of primetime programs, he admits it isn’t people like him making the decisions.

“I like Wilma Doesnt [an actress of Filipino-African heritage] a lot, but it’s probably a rare case for studios to invest in films with leads who look like Wilma Doesnt,” he said bluntly in a recent interview.

“Most [leads] have been handpicked by the studios. Perhaps the fact that there are a lot of mestizos has less to do with how casting works, than what studios or corporations feel the audience would respond to,” Castro said in a mix of Tagalog and English.

“[But] I’m not even sure it’s what the audience wants. It’s the perception of whoever is in control, whatever they believe the audience wants. Sometimes they base it on track records, figures, sometimes they do focus group discussions.”

And therein lies the chicken-egg conundrum at the center of the casting issue.

For the author David, the perceived demand for mestizo beauty is a self-reinforcing cycle.

“The masses have bought into this white/light skin ideal. So the media can now say that they’re just supplying what is being demanded.”

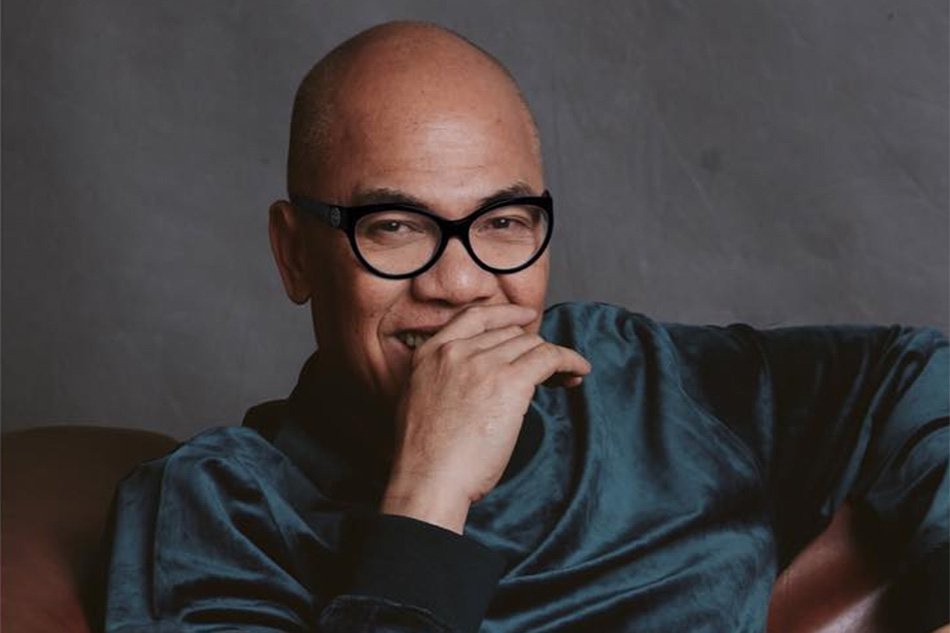

Veteran TV host and entertainment executive Boy Abunda, himself a darker-skinned Filipino, puts a more positive spin on the issue.

In a recent sit-down with Coconuts Manila, the Samar province native insisted that while the role of skin color in making stars of the past can’t be denied, it matters less today.

“Almost 30 years ago… I was told that it would be very difficult for me to get into the business, to break into the business because… well, I was gay,” Abunda said. “I was not beautiful. The words used were na ‘hindi ka kagandahan’ (you’re not that beautiful).”

Unfortunately, the industry’s definition of beautiful has seemingly changed very little in the past 30 — or even 100 — years.

Skin color and power

“Everyone would be mestizas except for the maids,” Gary DeVilles, an assistant professor of Filipino literature at Ateneo de Manila University and pop culture critic, said of the early days of Philippine cinema.

Devilles easily rattles off the names of light-skinned stars of the era who were explicitly modeled after American celebrities.

“For example, actress Paraluman was called the Greta Garbo of the Philippines for having a similar bone structure, figure, long brown hair, and similar eyes,” DeVilles said.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xSZh6-RI0y0

“Actor and singer Eddie Mesa, who was light-skinned, was packaged as the Elvis Presley of the Philippines.”

Filipino filmmakers looked to Hollywood not only in developing their technical skills, but also their concept of beauty, he explained.

“The United States fed this fascination with whiteness,” Devilles said. “Using Hollywood and films to perpetuate this whiteness – it brought white love.”

It’s a trip down memory lane with which Abunda was intimately familiar.

“There was a time when there had to be Tom Jones of the Philippines. We had to have the Elizabeth Taylor of the Philippines. Lahat ng ito, nangyari ito (all of this happened),” he said.

But more worrisome than the fetishizing of American celebrities, said Devilles, is the adoption of a casting tradition that rarely strayed from the Hollywood formula of casting whites as leads and African Americans as maids, criminals, or the target of cheap laughs.

In the Philippines, those with darker skin tones, such as the late actress Elizabeth Ramsey or even Castro’s current example, Doesnt, have often been typecast in supporting comedic roles as house maids or the best friend of the lead characters.

That’s not to say there have been no dark-skinned actors who maintained long, successful careers. They’re just a rarity. The most famous being Nora Aunor.

Aunor has starred in more than 180 films and dozens of TV shows since beginning her career in the 1960s and has received dozens of awards in the Philippines and international film festivals.

Her most memorable role was in the 1982 Ishmael Bernal film Himala (Miracle), in which she played a rural faith healer. The film was recognized by CNN as the Best Asia-Pacific Film of All Time.

“Nora Aunor broke the rules,” Devilles said. “She broke glass ceilings. But even as a lead, she’s typecast — it would be a maid, OFW, or victimized characters. You still have those binaries,” he added.

But few darker-skinned actors have enjoyed even that sort of pigeonholed success.

Whitney Tyson – a half-black comedian and actress whose star was on the rise in the 1980s — was featured in a 2016 GMA Network documentary that showed her living in poverty after her TV show ended in the mid-’90s and the offers stopped coming in.

In Tyson’s mind, it largely came down to one reason — race.

“It’s not a thing to cast black women like me anymore,” she told GMA in Tagalog.

Whether or not Tyson’s version of her fall from the limelight is completely accurate — and some, like Abunda, would contend she’s possibly overstating the racial element — the interview couldn’t help but strike a chord with other dark-skinned actors.

Fonacier remembered her shock when she first watched it.

“I remember my hairs stood up, I got scared and angry,” Fonacier said. “Whitney Tyson, because of her skin color, was relegated to comedic roles all the time. And she had to bear the brunt of hearing fellow actors spew out lines thrown at her, “baluga” (a Filipino word for black native), “sunog,” (burnt),” Fonacier said.

Those words are deeply familiar to her.

“Sunog and baluga were used so often while I was still in school because [my classmates] learned them from their parents,” Fonacier said. “There’s not even a specific instance I can remember because of how normal it was.”

‘Anti-pogi’

Both Castro and Abunda are quick to cite specific instances where non-mestizo actors have taken center stage successfully.

Castro pointed to the success of 2017 film Kita Kita, where neither of the leads — Empoy Marquez and Alessandra de Rossi — fit the profile of typical mestizo stars. The film grossed a total of PHP320 million (US$6.4 million), more than any independent film in Philippines history.

Another breakthrough last year was GMA-7’s casting of actor Jerald Napoles, another darker-skinned Filipino actor, in a lead role alongside Filipino-Spanish actress Marian Rivera in the fantasy series Super Ma’am.

“I recently spoke with students from ABS-CBN film school and they brought up the “anti-pogi” (anti-handsome) rom-com actors theory,” Castro said, bringing up what some have nicknamed a recent trend to cast non-mestizos in key roles.

“They asked, ‘Why have there been hits when the ‘anti-pogi‘ has been cast? What’s the appeal? And what does that say?”

It’s an interesting anecdote that one could see as evidence of incremental change in the casting world, but it also drives home another, more sobering, point — that the casting of non-mestizos is novel enough to drive discussion with film school students.

While Abunda freely admits he’s “cognizant” of the industry’s color issues, he too believes that real progress is being made.

“We are a mix of many things. That should be embraced. That should be celebrated,” he said.

“I think there is some pride now of who we are, of the color, of Filipino talent. We’re just waiting for the best [that’s] yet to come.”

Pushing back

The real question is just how long people in the industry, particularly the younger generation, will be willing to wait.

In August, Fonacier and her comedy troupe Sutukil Sauce went on the offensive with a viral comedy sketch that explicitly took on one of the Philippines’ most-profitable industries — the world of skin-whitening products.

The sketch flipped traditional ideas of beauty on their head with a mock commercial for a “brownening soap” that poked fun at “fleshy ghosts” with white skin.

While Fonacier said the sketch was lighthearted satire, it’s hard not to see it coming from a place of very real, and completely legitimate, anger.

Almost unbelievably, just four months after the clip went viral, Filipino netizens pointed out that an actual skin-whitening firm put out a tone deaf commercial that ripped off the look, tone, and even the music used in wholly unironic fashion.

Call it a bitter lesson in just how far things yet need to progress.

READ: Life on the drip: Tapping into a country’s color obsession

“The fact that the majority of our celebrities that are considered the ‘beautiful people’ are still light skinned or mestizo/a is a sign that not much has changed,” David said.

“The fact that people still openly made fun of how dark some people are — even wealthy and powerful dark skinned people like [former vice president] Jejomar and [senator] Nancy Binay — is a sign that not much has changed.”

All too aware of that reality, Fonacier knows that she — like so many others — has options to make her journey in Philippine entertainment a bit smoother: Accept being typecast as the maid or the sidekick, or get cosmetic work done to look more mestiza.

Neither are paths she’s willing to tread.

“I’m stubborn,” she said. “And I want to challenge these long-outdated messages on what Pinay beauty really is.”

You can’t help but root for her, but it is a challenge that will take a serious shift in industry, and societal, attitudes.

“Ultimately, it’s a machine that has some soul-searching to do,” said David.

“They have so much power to change the narrative. And because of this power, I think they have the responsibility to put out a narrative that is not harmful to the health and well-being of Filipinos,” he said.

“Instead of perpetuating and reinforcing a harmful narrative, they can make brown skin cool.”