Ryan (not his real name) got his swab test in early April, at the height of Manila’s sticky summer and two weeks after the capital went into lockdown for the coronavirus. The first thing he thought of when the word positive jumped off the official papers was, “What about the kids?”

As if things weren’t difficult enough already, the burly 38-year-old dad of three—who requested anonymity—had already isolated himself from his family after his old man experienced shortness of breath. Ryan’s father, who he drove to the hospital regularly for checkups, would later flatline from heart complications. Weeks later, the senior figure’s swab results would confirm that he too was COVID-19 positive before he died.

The heavier-than-bricks circumstance is enough to rattle even the most level-headed people.

“It’s a real mind fuck,” the recovered dad told Coconuts Manila during a call, as he recalled the months-long ordeal from his home, while two of his rowdy toddlers can be heard in the background. Ryan’s younger kids were only told that their dad was previously sick. But his 12-year-old knew what COVID-19 was, and Ryan had to constantly assure him via chat that he was fine. He’s had to juggle grief, worries about his family and his own sick state, and on top of that continue being a dad to his kids.

While not all parents are able to dust things off and resume with life as usual at the end of a very unique set of challenges the way Ryan has, scores of very tired people are caught between worries of the outbreak, and the added difficulty of raising less-seasoned humans under their roof who rely on them for physical and emotional security.

How parents are responding to the threat of a pandemic is a less popular conversation that—like many things that happen indoors—is being drowned out by the world’s current headlines. But in Filipino culture, where family is widely considered the foundation of social life, parents have to contend with caring for kids under the “new normal” setting, while they readjust their kids’ shrinking social circles, ensure their safety from a killer virus, and on top of that, be an emotionally strong and reliable figure for the tots. It’s a 24/7 job—it not only doesn’t pay, but parents are the ones who do the paying.

If being a Pinoy parent was difficult pre-pandemic, then it sure as hell isn’t a walk in the park now.

Reducing exposure with a smaller child

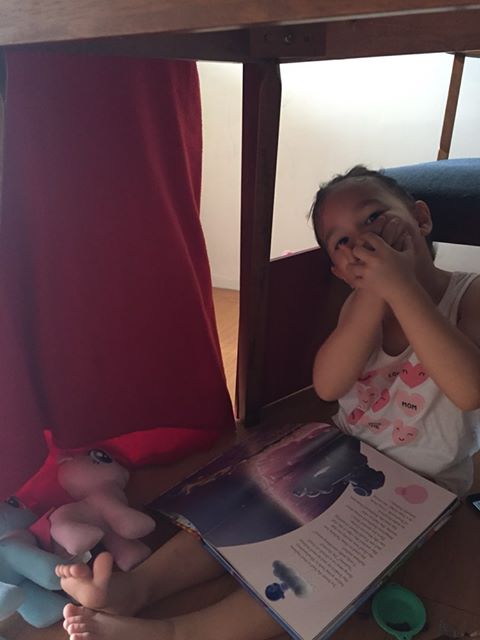

Plucky preschooler Marley has not seen a greater threat to her outdoor playtime and social activities than the coronavirus—which she’s resorted to call by a less ominous name, “germsie.”

“We simplified the situation for her as best we could, we said it was unsafe to go out because there are germs in the air,” Marley’s mother, Filipino food entrepreneur and writer Mich Lagdameo-Roque, told Coconuts in an email.

“Her favorite thing to talk about is ‘when the germsies are gone…’ then she talks about going back to school, visiting her cousins, and her other pre-pandemic activities,” Roque said.

Marley’s rather endearing quirks are a welcome intermission from virus fears, and from a palpable tension that could be felt inside the walls of their condominium building in Quezon City’s Eastwood Village.

“I do notice a small undercurrent of panic every time we leave the house to check on my mom in another condo unit. Marley shouts at us to ‘Please wear mask!’” Roque recalls.

Pre-pandemic, she would often drop off Marley next door to her mom, who lives in the same building, a lobby’s trip away. She would babysit her grandkid while Roque cooks and attends to her food business, and tries to cram in as much writing projects in her packed day. She does this while her husband Lamar, also a working parent, is out shooting TV drama serials.

“We only spent time together as a family on Sundays because work really took up 90 percent of his week,” she said about her husband.

“I really relied on my mom for childcare support because I was working from home full-time, had a business to attend to, and I couldn’t handle Marley on my own,” she added.

With lockdown imposed, and shooting grounded, her husband is around to help out at home. They’ve cut back on Marley’s grandma visits by half “to reduce exposure,” though they still have to drop by twice a week to bring her mom groceries and medicine.

Roque said on top of immediate fears of being infected with the virus and anxieties about what the future holds, she’s worried about the kind of world Marley will grow up in.

“We know that the effects of the virus will last long after a vaccine is found. It scares me to think how inhospitable and uninhabitable the environment she’ll grow up in will become. It’s completely changed the way we approach parenting,” she shared.

“We want to raise Marley with as much grit and compassion as possible because she will have to be part of a world that has to survive such a thing as a pandemic in more ways than one,” Roque added.

What happens when you have a brood of kids?

Meanwhile, at a neighboring Quezon City village, four kids engaged in horseplay in a garage-friendly inflatable pool seems to signal that things are pretty much alright. Pretty much.

The kids’ mom, Paulynn Bagunu-Castillo, 38, worked in a bank before she decided to look after the brood full-time—the youngest now 5 and the eldest a 16-year-old.

Castillo is used to at-home challenges owed to mothering kids for over a decade and a half. The kids were already off school for the summer, so very little changed in her routine when the enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) was imposed on March 17.

That was until she started getting panic attacks.

“My mouth went dry, I got dizzy, I had palpitations; my heart was beating out of my chest. It felt like I was going to collapse,” she said, about the near-minute-long bouts that were identified as anxiety attacks by the family doctor after she described it over the phone.

It was an alien experience that the mostly unruffled mom of four tried to dismiss.

“I consider myself a very chill and relaxed person. I’m lucky to have a helper assisting me with the kids’ meals and house chores. I’m used to staying at home. So I don’t know why I had panic attacks. I didn’t even know I was having it. It’s not really my style,” she laughed, attempting to shrug it off.

The doctor couldn’t pinpoint an exact trigger to the attacks. But for a while before that, she and her husband, who runs a textile printing business, have been having trouble sleeping while sheltering in place because of stresses brought on by the pandemic.

They’ve been taking melatonin, an over-the-counter sleeping aid to keep them from waking up late at night. The sleep cycle drug does nothing for her panic attacks, but the doctor’s advised her to limit social media, news consumption, and other potential sources of stress for the time being.

Castillo shared that the sleeping problems and the panic attacks might be linked to worries about her family’s safety and security. But despite the very physical toll it’s taking on her daily life, she’d insist on not wallowing in her predicament because everyone is going through a tough ordeal.

“I was supposed to be the cool one, Donald [Castillo’s husband] is the one who worries about the business being closed because of ECQ, about the welfare of his employees, about the family, and of course because the bills keep coming. I would tell him it’s not just us that’s worried, the whole world is worried,” she added.

With more kids in the family, of course there are more warm bodies to feed, survey, and mother. It can also mean life in a non-minimalist household: a cluttered house still passes for a clean house, and kids’ raucousness are daily occurrences that you simply get used to.

When her panic attacks set in, Castillo would need to calmly ask her children to shush and stay inside their rooms for a bit until the flare-ups pass. It’s one of the very few times she’s allowed to be selfish.

But despite this, she says having four kids works to their advantage in some ways. The younger kids enjoy sleepovers at their older brother’s room in lieu of having their friends come over, for one. And for another, it helps shift responsibilities around.

Her boys Enzo and Lucas, aged 10 and 16 need a little less hand holding when it comes to virus talk. But with her 5-year-old on the other hand, it’s a different story.

“Sabine would say, I hate why these Chinese people made it. And I would say, where did you hear that? Lucas tells me even in cartoons they also touch on the corona. [The show] OddBods has an episode about it. She probably heard Chinese and formed her own conjectures,” Castillo said.

“So I had to tell her, Chinese people didn’t make it, it just came from China. She’s the curious one who would always ask what COVID-19 was. I would tell her it’s just like any other virus but it’s more dangerous,” Castillo said.

Pushing through physically and emotionally

For at least a week since he got tested and waited for his results to come in, Ryan went through the laundry list of COVID-19 red flags: cough and colds, a sore throat, body aches, and a fever that registered upwards of 37ºC. The only reason he wasn’t admitted to a hospital and isolated instead at his parents’ house is because his symptoms stopped short of breathing difficulties and his x-ray results cleared him of pneumonia.

He sequestered himself in a room where his food, clothes, and medicine were transported via a stool that sat next to his closed door. He used a separate bathroom, was careful not to touch anything outside his room, and he sanitized wherever he went in the home where his two younger brothers, mom, and house help were also sheltering.

During those tense times, calls to his wife and kids made him a little overbearing.

He would have food delivered to his family. “But before I could ask them if the food tasted great, I’d first ask, ‘Did you wear a mask when you received the delivery? Did you wipe drinking water gallons that needed to be wiped? Did you wash your hands before eating?” Ryan would probe.

His paranoia would launch arguments with his wife, who would repeatedly tell him that she too, as a parent, knows what she’s doing. In hindsight, Ryan said he was overcompensating for not being there for his family physically.

But he had a plan. He followed a strict routine and schedule. Without it, he says, he probably would have lost his head. He resolved to take things a day at a time.

“I had a calendar where everything was plotted. I had alarms set for antibiotics and vitamins I needed to take throughout the day, an alarm for when I should eat, for when I should go to sleep, when I would go to Mass, when I should pray, when I needed to call my family.”

“I’d cross off one more day on the calendar and that meant being one day closer to coming home to my kids.” He kept tabs on them through chat and calls, and focused on reminding them to wash their hands and keep distance from delivery guys, instead of dwelling on the dread that they’d catch what he had.

“Even though I was scared, there was no scenario where if I slept it off and woke up the next day everything would be over, that wasn’t going to happen…so I focused on what I needed to do, and what they needed to know to help them survive this,” Ryan said.

When he rejoined his family in May after testing negative for the virus twice, his homecoming was in time for his 5-year-old daughter’s birthday.

The local government conducted rapid tests in their village, and his entire family all got negative results. “I’m aware that rapid tests aren’t as reliable as swab tests. But it was still a big deal for me that they all tested negative. We also monitored the kids for flu-like symptoms,” Ryan shared. Luckily, none of the symptoms came.

In the weeks that followed, he and his family got flu shots.

He didn’t believe a vaccine against the flu would keep his kids from catching COVID-19. But he thought it might help eliminate one less threat. It would cancel out the needless agony of getting swabbed and waiting on test results that would turn out negative because your flu-like symptoms was really just a regular flu.

The country’s “current system of processing tests is really sluggish, and that adds to already sick people’s anxieties,” says Ryan.

“I wouldn’t wish that on my kids.”

Finding joy in the little things

Being a parent in the time of a pandemic is a circus act of sorts. It requires balancing priorities, juggling responsibilities, maybe even walking through a thin tightrope of childcare and selfcare. It requires so much energy. But that doesn’t mean the same energy can’t be channeled into things that bring you joy between grief.

A chocolate-flavored popsicle on Roque’s last grocery run made her daughter ecstatic, and her husband de-stresses with music. “I unfortunately discovered K-Dramas. Haha!” Roque said, pointing out that joy can be found in the little things.

“Cheesy as it sounds, it’s true that you start to appreciate the little things. Being isolated from the rest of the world, we learn so much about each other pretty much in a vacuum. It turns out it doesn’t take much to make us happy,” she said.

Like any family unit, Roque acknowledges that friction is inevitable. And while a kid brings you joy, she said it can be frustrating to constantly be in “teacher mode,” especially when you just want things done quickly.

“It’s true what they say that when you’re a parent you never really have a day off. But we honestly feel our family’s gotten stronger together because we give each other space to have our ‘off’ days as we individually react to the pandemic stress.”

Ryan, who lost 12 pounds during his COVID-19 ordeal says he and his family take pleasure in the simple instance of a cake.

“Three birthdays have gone by since lockdown, then Mother’s Day. Whenever there’s an occasion, our family has to have cake,” he said.

Castillo has been turning to cardio workouts to decompress physically and mentally. She’s also cooking and baking with her kids.

“Having kids around is difficult, yes, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. My kids are my greatest source of joy,” Castillo said.

Also read:

Nightingales in Peril: Filipino nurses put their lives on the line in the UK

‘Comfort’ or con? Despite money, education, well-off Filipinos turning to questionable treatments

For Beauty and Country: Gay Filipino men in the world of pageants

It’s a Small World: Living sustainably in the Philippines’ sachet economy

Mind the gap: In the Philippines, language isn’t about words, it’s about class