“Please stop! I have a test tomorrow!”

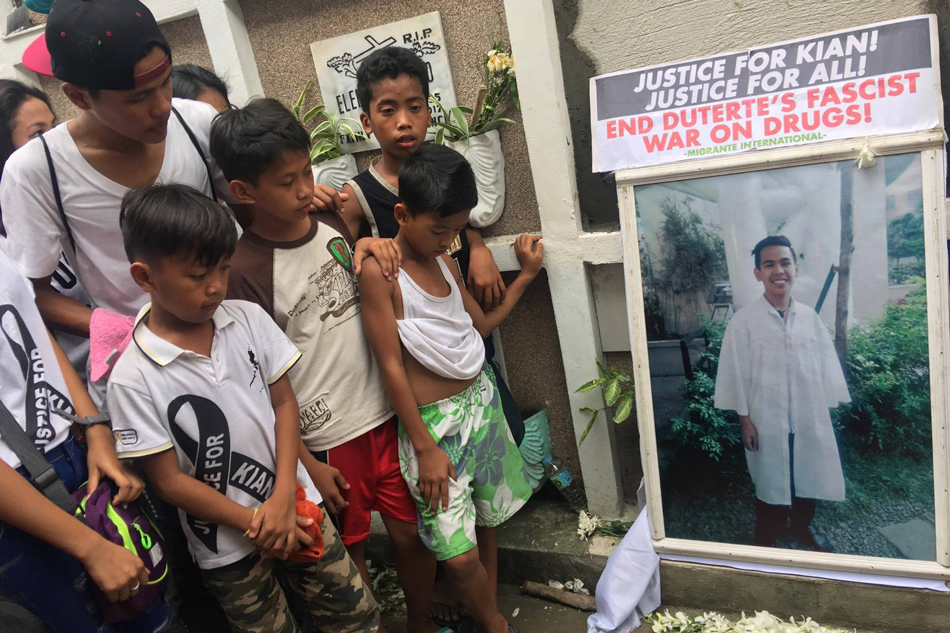

Those were the last words the neighbors of 17-year-old Kian delos Santos heard the high schooler say on the evening of Aug. 16 as he was dragged into the dark alley where he was later found dead.

READ: Manila police say they shot a 17-year-old out of self-defense, CCTV shows otherwise

Carl Angelo Arnaiz, 19, and 14-year-old Reynaldo de Guzman went missing a day later.

Carl Angelo was found executed in Caloocan, while the body of a boy de Guzman’s parents believe to be their son was found 100 kilometers north in the province of Nueva Ecija with 30 stab wounds and his head wrapped in tape.

The trio weren’t the first minors to be killed since the start of President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs, and there’s little reason to believe they’ll be the last.

According to a study released last month by the Children’s Rehabilitation Center (CRC), 20 teenagers between the ages of 15 and 17 have been killed by masked vigilantes, police, or stray bullets since the crackdown began last year. Six children under the age of 13 and two pregnant women have also been killed.

If death tolls offered by human rights observers are to be believed, those 20 teens are among 13,000 people killed to date.

And their deaths can’t be simply laid at the feet of a rogue police department. In a very real way, they are “just following orders.”

“So to the last man I said, to the law enforcer, to the military guys: Destroy the apparatus. And I said, ‘Oh, sir, if they are there, destroy them also. Especially if they put up a good fight. Oh, ‘pag walang baril, walang – bigyan mo ng baril (If he has no gun – give him a gun). Here’s a loaded gun. Fight, because the mayor said let’s fight.”

The same man who seems to be suggesting planting guns on suspects followed it up with a similar message a few months later.

“I am the only one who will tell you to your face to kill those sons of bitches? Who else would? If you can’t do it, I’ll kill them myself. Then they fight back… If they don’t fight back, make them fight back.”

If those words sound familiar, they should. They were President Rodrigo Duterte’s exact words to police officers last December 2016 and again in July while visiting a military camp.

These were also the specific directions the officers involved in Kian’s killing are alleged to have followed. He had no gun, so he was given a gun, witnesses say.

The official police report said Kian shot first and officers were forced to fire back. But the CCTV footage tells a different story, showing Kian dragged into an alley by two larger men. So does the coroner’s report, which found that he was shot from behind, indicating that the police department’s story that Kian was killed for fighting back is likely a fabrication.

His is just one of an estimated 3,000 killings now justified because police claimed the suspects “fought back.”

Senior police officials told Reuters in a special report last April of a kill quota and cash reward system: PHP20,000 pesos ($400) for a “street level pusher and user,” PHP50,000 for a member of a neighborhood council, one million pesos for “distributors, retailers and wholesalers,” and five million for “drug lords.”

Human rights investigators also found that police were being pressured into filling “kill quotas” in police operations, something police chief Ronald dela Rosa has vehemently denied.

While these facts have yet to be proven definitively, the recent teen deaths seem only to confirm what human rights investigators and journalists have been telling us all along: Abusive and corrupt law enforcers are killing with impunity.

So when Mr. Duterte says that he never told cops to kill innocent people, we wonder if he’s forgotten about the numerous, specific times he’s given police leave to kill with impunity or if his memory is just increasingly selective about the things that come out of his mouth.

This has to stop.

We’re done with trying to understand where he’s coming from, with the (lame) excuse that his humor is common in the Visayas — a region ostensibly known for a more violent and crude type of humor — and therefore the nation should not take him literally.

We’re done listening to his defenders try to explain that he didn’t mean what he said. We’ve watched them insist that the media has taken the president out of context or misquoted him, or that media reports didn’t reflect the “nuances” of what he was trying to say.

Nowhere else in the world would a communications team ask the press or the public to not take the commander in chief’s words literally.

OK, maybe one. Politico: Trump adviser: Don’t take him literally, take him symbolically

But it’s not supposed to work like that. Not for this president or any other.

We’ve had enough. His words are killing people.

Though Mr. Duterte may not have fired the bullet that killed Kian, his words lie behind his death just as assuredly as they do behind that of Carl Angelo and every other supposed “drug dealer” — now over 13,000 of them — left dead on the streets without due process.

And until he admits this — to himself and to the nation — more young, innocent, people will continue to die.