By James Chin, University of Tasmania

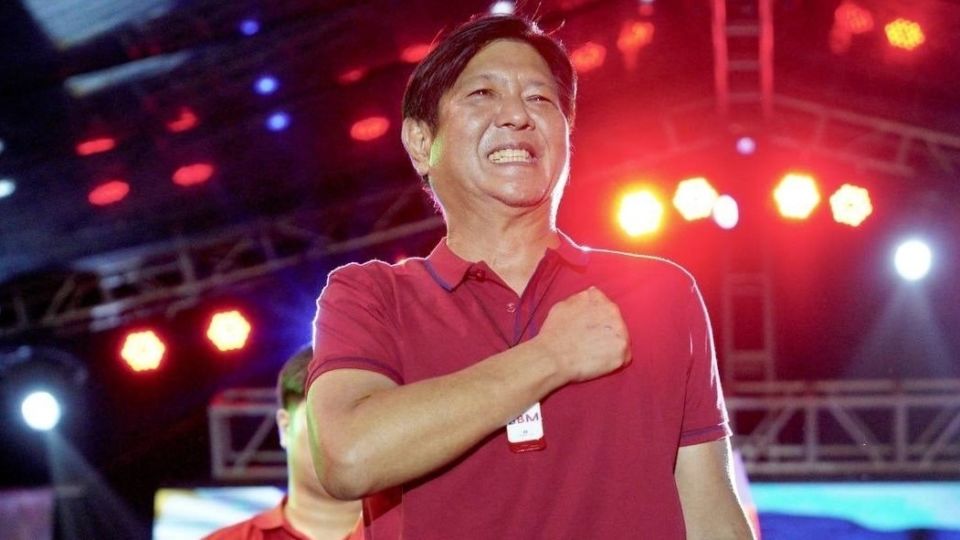

While there is widespread nervousness at the victory of Ferdinand Marcos junior in the Philippines, for many of us it was a reminder that “blood” is still an important element in the politics of the developing world.

Before you get smug, it’s called “political dynasties” in the developed world. In the US, it’s the Kennedy, Bush and Clinton families.

In much of Southeast Asia, the idea of political blood is taken much more seriously. Despite the modernization process, politics is still stuck in the old ways.

A brief look is disturbing. In the Philippines, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo and Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III both succeeded their parents as president of the Philippines. In Indonesia, Megawati Sukarnoputri is the daughter of the country’s first president, Sukarno. In Thailand, Yingluck Shinawatra succeeded her brother Thaksin as prime minister. Singapore is ruled by Lee Hsien Loong, son of Lee Kuan Yew. Najib Razak is the son of Malaysia’s second prime minister, Abdul Razak Hussein. And Hun Manet, the son of Hun Sen, is almost certain to take over Cambodia soon.

These are the most prominent ones. The truth is thousands of others in the region hold high political office due to their bloodline.

Others are waiting: Mahathir Mohamad’s son Mukhriz in Malaysia, Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono, the son of former Indonesian president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY), Panthongtae Shinawatra, the only son of Thaksin, all have a shot at their nation’s highest office. Hishammuddin Hussein, son of Malaysia’s third prime minister, is in the same boat. If they did not come from rich and powerful families, it is unlikely they would ever attain high office.

Are they simply a natural product of political families? The argument goes that if you grow up in that kind of household you cannot escape your “calling”. Some even liken it to “national service”. The other argument is that since it’s a democracy, if the polity voted for them, that should be the end of the argument.

But the reality is that political dynasties are created, and often accompanied by formalities steeped in custom and traditional political culture. They are nothing to do with meritocracy. In Southeast Asia, it’s often linked to “patron-clientism”, where a powerful person (patron) and a follower (client) mutually benefit from the relationship.

In a nutshell, why should you hold high office just because you are born with a certain surname or lucky enough to be born into a particular family?

In almost all cases, political dynasty members use their superior wealth, connections and education to rise. Along the way, they attract the followers of their forebears and keep them loyal with patronage, sometimes called the “coat-tail effect”. I take the view that political dynasties, in all societies, are bad in the long run and have negative consequences for political development.

First, political dynasties hinder meritocracy and fair competition. In rural areas of Southeast Asia, it is extremely rare for a political unknown to defeat a “name” that has been in power for generations. This explains why the power bases of many political dynasties are often found in rural constituencies.

Second, political dynasties promote the idea of political elitism. That is, the selection process is closed and the leaders are drawn from the same pool of people.

Third, political dynasties are closely linked to economic power. Concentration of political power among a few families benefits a narrow set of economic interests. This process institutionalizes economic and income inequalities and creates a culture in which “connections” become the most important criteria for everything. These political families are able to claim a major portion of the state’s resources legally through their control of the political system, leaving the country vulnerable to corrupt practices.

However, it seems political dynasties’ hold on politics in Southeast Asia remains unshakeable. Some countries have “term limits” to stop political dynasties, but they are totally ineffective in practice. For example, there is nothing to stop a brother or sister from the same political family succeeding each other.

Will social media and the internet change the situation? It is very unlikely. The most important criterion for political change is probably education, which means an education system that teaches citizens to be critical and think in a rational way.

But in Southeast Asia, state education is about producing citizens who obey authority – in bureaucratic speak they are called “loyal” or “patriotic” citizens.

So, should we be surprised by Bong-Bong Marcos’s victory? Not in the least. There will be similar victories by people with very familiar names in the future.![]()

James Chin, Professor of Asian Studies, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.