When Metro Manila went on lockdown, life became more difficult for low-income Filipinos.

Thousands were stranded in the city and even more lost their jobs in one quick swoop. Unemployed Filipinos, who were already struggling in their minimum wage jobs to begin with lined up in the streets and begged, as the number of COVID-19 cases continued to climb.

Despite the despair surrounding the country, the pandemic has brought a spirit of bayanihan (“camaraderie”) as well. Various non-profit organizations have raced to help the most vulnerable, such as children from low-income families. From feeding the abandoned to equipping the country’s medical workers, a handful of dedicated non-profit organizations have stepped up.

Coconuts Manila spoke to some charitable organizations which have come to Filipinos’ aid in a time of need. While they are succeeding in their mission, they are also fearful that funds will eventually dry up, which would severely affect those who rely on their help.

An Empty Refrigerator

Along a quiet street in Metro Manila’s Marikina City is Meritxell Children’s World Foundation, a shelter for orphaned and abused children. At least 19 children stay in the home, many of whom are between the ages of six and 11 years old. In times of uncertainty, this serves as a safe harbor for these children, a protection against the chaos going on around them.

Read: Pandemic Parenting: How COVID-19 is making childcare challenging for these Filipinos

Executive Director Leah Tomelden-Lagmay founded the charity in 2008 with college friends. Lagmay, along with the other administrators, are volunteers while those who are involved in their day-to-day care are employees.

“We purposely took in older children because they are most in need of [an organization that would] process their documents. Their [adoption] papers are not processed as quickly. The government doesn’t have the funding to process the documentation [and] we saw that there was a gap in the care of the children. The social services [in the country] aren’t advanced,” Lagmay said.

Prior to the enforcement of the enhanced community quarantine on March 16, Meritxell went on lockdown to prevent their staff and children from getting infected with the coronavirus. However, the lockdown proved hard on the shelter. Donations moved to a trickle when visits were banned.

“The thing is we used to receive donations regularly on weekends when people would visit–either in cash or in kind. We used to receive donations regularly but when we checked our bank accounts [after we went on lockdown], there was a massive drop in donations,” Lagmay said in a phone interview.

The quarantine also meant that it was hard to leave to buy food for the children and the staff, and at one point, the charity’s refrigerator was left empty.

“In the past, we would go to the market twice a week. Our [fridge] is always full but we couldn’t go to the market as more places are getting affected with COVID and because of the quarantine,” she said.

“It was getting more and more difficult. We have children and caregivers to feed three times a day. We cannot keep feeding them canned goods.”

And so, Lagmay turned to social media, sharing a picture of the shelter’s empty fridge on Facebook. The post went up around lunchtime and by evening that same day, it already had almost 300 shares and was even featured in a prime-time news program.

Lagmay credits the post’s success to expanding their pantry to more than just canned food, believing that it “somehow [enabled the shelter] access to nutritious food.”

While the story seems to have a happy ending, Lagmay believes the pandemic will take many years to get through and will continue to test their organization over and over. She knows millions of Filipinos have lost their jobs, and money will be tight.

At this stage, she’s doing everything she can to cut down on costs. For instance, things like a leaky faucet, she said, mean unnecessary expenses.

“When you can’t increase [your] income you cut down on your expenses. Our expenses, utilities, water, electricity–that’s the first thing we look at. We have started using a pail when we wash. When we take a bath, we limit the amount each child uses,” she said.

Disrupted Lives

While Meritxell is involved in actively caring for children, non-profit organization World Vision focuses on helping communities whose lives have been drastically changed by the pandemic. The largest non-profit organization in the Philippines, World Vision, which was established in the country in 1957, says it helps up to 1.5 million children each year, as well as their families.

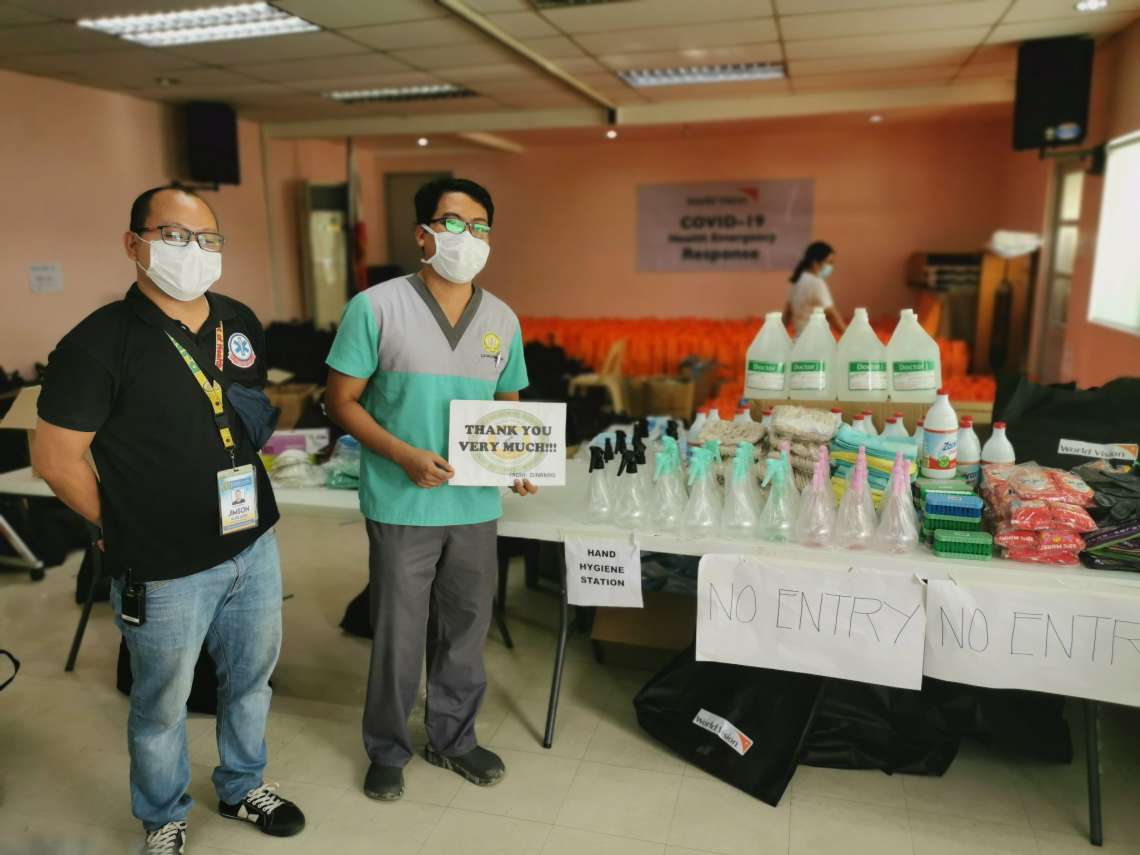

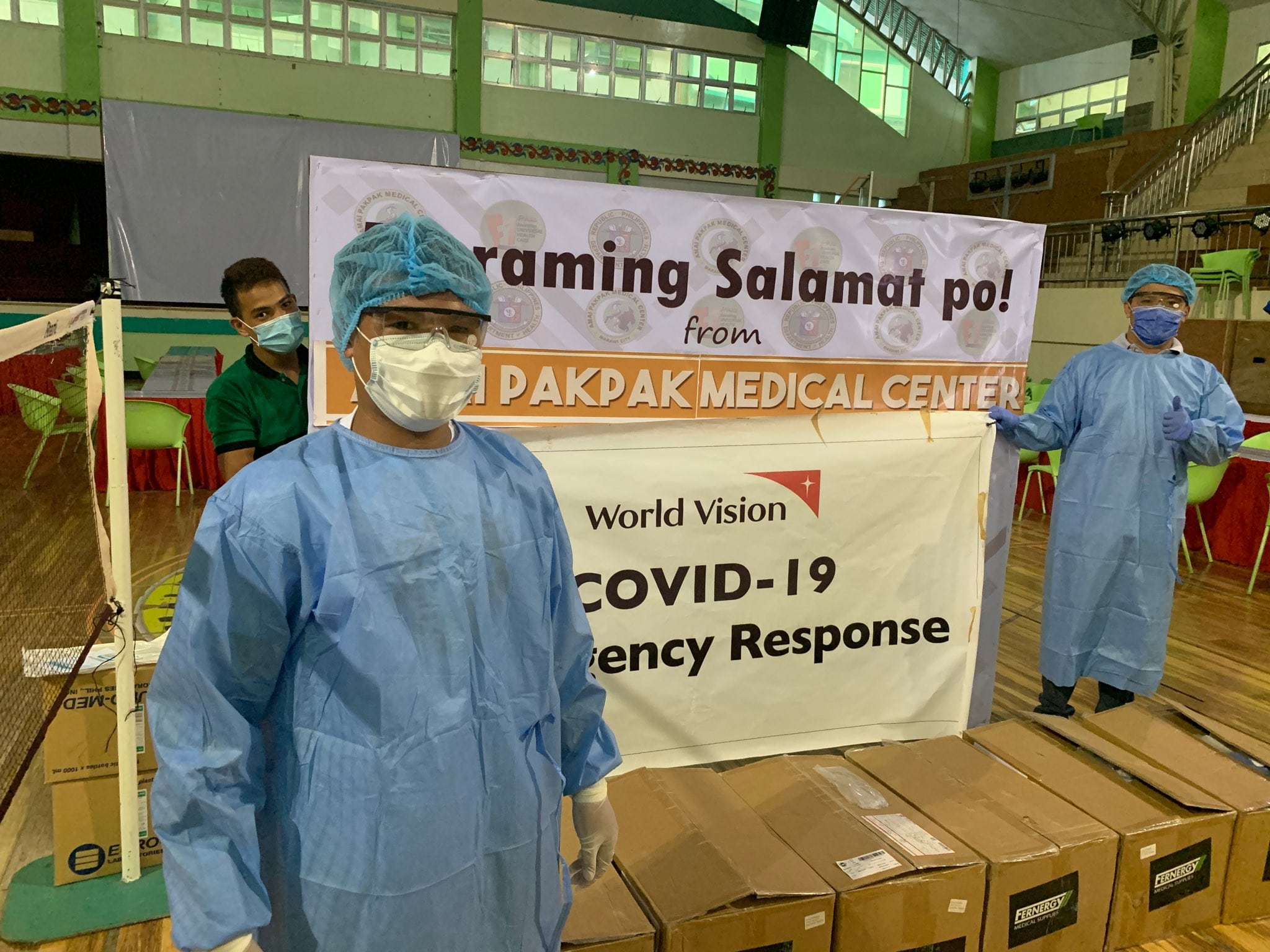

Ajab-Aram Macapagat, the organization’s humanitarian affairs and emergency director, said the organization has been busy with various projects, such as educating families about COVID-19, sending protective gear to healthcare workers, and even giving cash donations to those in need.

“We support the government with information dissemination [about COVID-19]. We talk about the [importance of] hand hygiene, using soap and water, and other messages that would help in preventing the spread of the virus. Likewise, World Vision has also distributed sanitation kits [in different towns]. This is composed of soap, toothbrushes, alcohol, and masks for children and their families,” Macapagat told Coconuts Manila in a Zoom interview.

World Vision is particularly worried about the economic impact of the pandemic. At least 2 million Filipinos have lost their jobs due to the lockdowns imposed by the Duterte government, and the World Bank expects poverty to become much worse as the country sinks deeper into recession. Widespread unemployment has led the organization to hand out cash to ailing families.

Read: Nightingales in Peril: Filipino nurses put their lives on the line in the UK

“We have also initiated our cash transfer programming. It’s a provision of cash to the families because we acknowledge their multiple needs and these affected families need to prioritize what they need [to purchase].”

As many organizations mobilized during the pandemic, Macapagat said they, fortunately, did not encounter any problems with fundraising, despite competing with other cash-strapped charities, hospitals, and even local governments. He said individuals have stepped up and donated to their initiatives.

Macapagat said that in the past, donors could not feel the impact of a crisis because they occurred in “far away” places, such as Mindanao. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has been felt by everyone, regardless of their location.

“You can see the responsiveness of the community, of the people to support the initiative. It has also been a challenge because some of our individual sponsors have already expressed financial difficulties,” he said.

A 12-year-old World Vision beneficiary who lives in Bukidnon told Coconuts that her life almost ground to a halt when the lockdown was first implemented in March. Nila (not her real name) said her father lost his construction job and her school closed down.

“We are scared to go out. It was just so lonely. We couldn’t go out to play with our friends. It was also hard because we couldn’t buy food,” she said.

Her mother, Catchy Landero, said they had to find ways in order to survive those early months of lockdown. While she got government assistance, the PHP6,000 (US$122) her family had received was barely enough to sustain their needs.

“No one could work. We had to borrow from our neighbors, from other people. As of now, things haven’t gotten better because we still have to pay our debts,” she lamented.

Her daughter is grateful that World Vision helped their community by giving them relief goods.

“They gave us face masks, rice, disinfectant alcohol, toothbrush, and school supplies. They also taught us how to wash our hands properly. And they taught us about child protection [laws],” Nila said.

The quarantine has since been loosened in Bukidnon, and Landero is hopeful that things will get better.

“Even if things are like this, life has to go on,” the mother of two said.

Meanwhile, World Vision’s Macapagat is counting on people to continue donating to the charity organization, so that Landero and thousands of other people can receive financial support.

“We acknowledge that Filipinos are generous and supportive, but if somehow their own economic activity is affected, this will definitely pose a challenge for us,” he said.

Unique Childhoods

Similar to World Vision, Save the Children Philippines has been providing urgently needed hygiene supplies to children living in poor areas in cities such as Navotas, Taguig, and Caloocan since the quarantine started in March. Before the pandemic hit, Save the Children gave health and nutrition services to residents, learning materials, and organized vaccination programs for kids.

Despite the crisis, the organization said that they actually witnessed a 19% increase in donations from March to July this year compared to the same period in 2019. The organization declined to disclose to Coconuts how much this percentage amounted to, but this amount has made it possible for them to fund many of their projects in Metro Manila’s urban poor communities.

Among their projects are cash transfer programs, which they started due to the anxieties expressed by the children, who told them during calls that they were worried about food and other necessities because their parents have lost their livelihoods.

“There is a need for cash assistance, the need for food, and access to healthcare. That’s the automatic need of children who grew up in urban poor communities because their parents do not have stable jobs. There was a disruption in their livelihood activities,” said Balinton.

Jovelyn, a 16-year-old beneficiary living in Pasay City, confirmed what Balinton said.

“Things have changed. Life became tougher. My parents had no jobs; there was no way to buy food. All we could do was wait for the government’s help,” she said.

Her family received government dole out, but “it wasn’t enough because so many people here needed it as well.”

While the parents are in turmoil over making sure everyone is fed, it’s clear that their children are also struggling—but more so with how to process what’s going on. During the early stages of the lockdowns, the children were extremely worried over the health of their parents and also had doubts over the accuracy of the information that they would read online about the coronavirus, Balinton said.

“One of the main anxieties they had was to be infected and to lose their loved ones … They are also worried if they are getting enough information. When COVID-19 first started, there was so much information on the internet, social media, and not all of them are credible. They read a lot of information online and they worry that these might be fake news that would later cause problems,” the charity worker said.

The children’s lack of access to food and other necessities have pushed Save the Children to continue with their work. As the pandemic continues, they’re counting on their supporters to not abandon them and their beneficiaries. While donor fatigue may happen in the future, Balinton remains positive that they will not be failed by their supporters.

“One thing is clear based on experience. There will still be donors who will help, even with small amounts. Based on our experience, if we keep them updated with what’s happening, tell them the impact of what they have given, what the children are saying, they will continue to donate,” he said.