On a sweltering summer day in May, a portly woman sat handcuffed in front of a cop dressed in a white hazmat suit. The two of them were inside a shanty in Taguig, in a poor Philippine community that stands in stark contrast to the city’s gleaming skyscrapers and malls. As the television loudly blared a drama show in the background, the cop, whose face was hidden by a mask and a pair of goggles, read the Miranda rights from his phone. He listed the laws that she had violated and said that like all accused, she had the right to remain silent, and choose a lawyer to defend her in court.

The 28-year-old, whose arrest was recorded on video by the police, was accused of committing a horrific crime: she forced her two daughters and two sons to perform sexual acts in front of a camera, which, in turn, was live-streamed to foreign pedophiles in exchange for money. Making it worse was that she did not act alone; a neighbor worked in cahoots with the mother, visiting remittance centers to withdraw the clients’ payment.

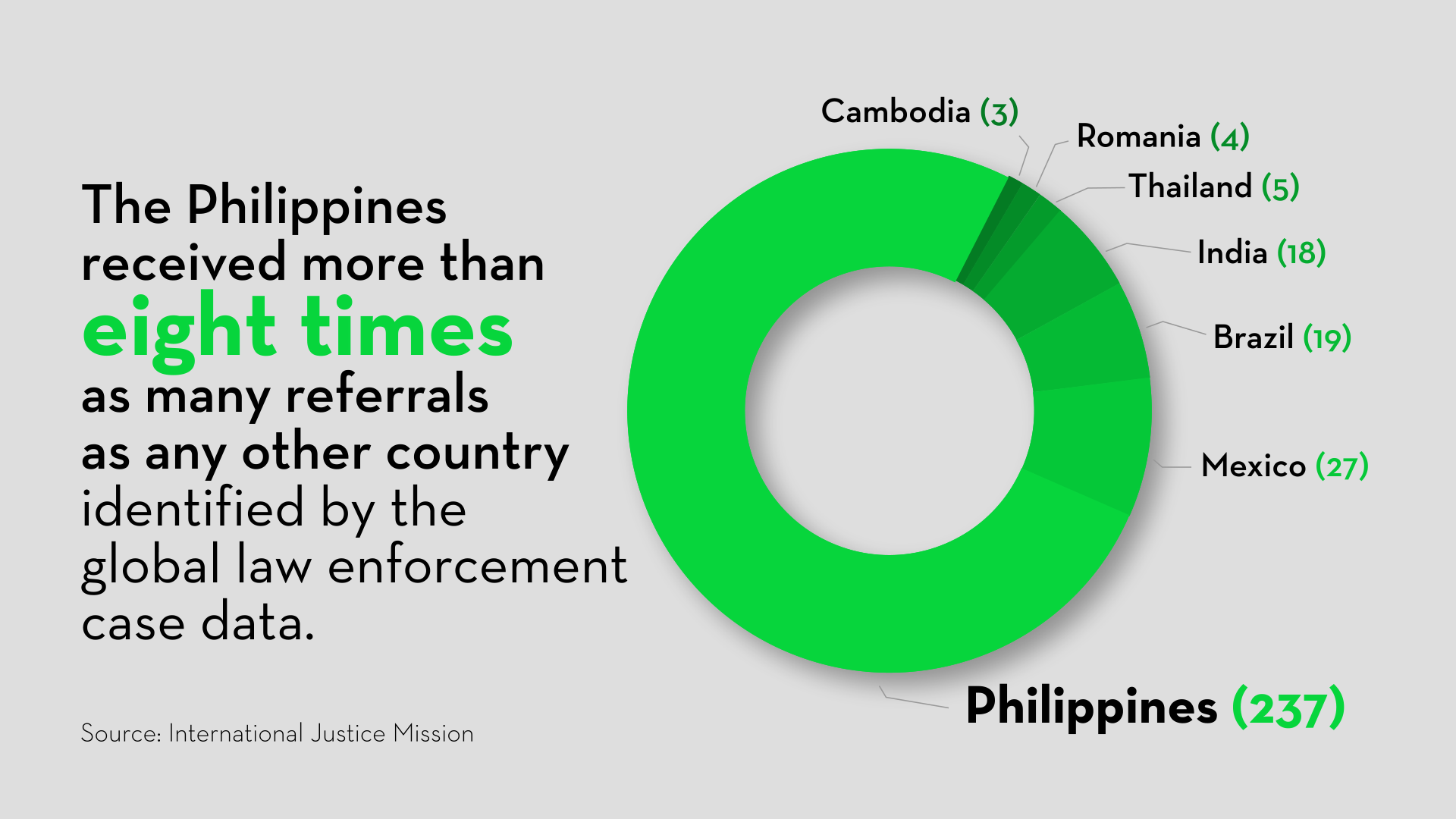

In the Philippines, where Catholicism reigns and talking about sex is almost taboo, the sexual exploitation of children on the internet happens far too often. The country is now known for being the number one source of child sexual exploitation videos and images, according to the International Justice Mission, which tracks the extent of the crime globally.

And COVID-19 is not helping. Children have been stuck in their homes, making them even more vulnerable to abuse. The United States-based National Center for Missing and Exploited Children attributes an almost 270 percent increase of possible online sexual exploitation cases of children (OSEC) trapped at home during the pandemic, with 279,166 cases recorded from March 1 to May 24, 2020, up from the number logged in the same period in 2019.

The Duterte government has expressed concern and vowed in January that they would go after OSEC perpetrators. They have their work cut out for them — OSEC could not have proliferated to such a degree if not for deep-rooted poverty in the country. This, coupled with Pinoys’ fluency in English, makes it hard to eradicate the sexual abuse of children.

As Coconuts has learned in this months-long research, the Philippines cannot act alone — if it intends to win the war against pedophiles, it badly needs the help of foreign governments and tech companies to go after the men and women who prey on vulnerable children.

Money, the Root of All Evil

The mother in Taguig City whom the police forcefully arrested in May 2020 is not an outlier. A study conducted by the International Justice Mission has found that most OSEC perpetrators — those who offer Filipino children to foreign pedophiles — are almost always the kids’ parents.

Parents do this to make ends meet. Cases have even increased amidst the pandemic because millions of Filipinos have lost their jobs and countless businesses had shuttered due to the government’s lockdowns, according to Sheila Estabillo, the Project Manager for Plan International, a children’s rights organization that seeks to educate Filipinos about OSEC.

“Poverty remains to be the main driver here in the Philippines why [children] are being peddled to pedophiles. Especially now that there is an economic fall out because of the COVID crisis,” Estabillo said.

Col. Sheila Portento of the Philippine National Police Women and Children Protection Center attests to this. Portento, who leads the investigation of hundreds of OSEC cases in Metro Manila, said that suspects are driven by their need for money.

“The excuses that they give are unacceptable. Like [they tell me the money] will be used to pay the rent, to pay the electricity bill. That’s why the child victims are easy to convince because this is what their parents tell them, that if they don’t do what they are told, they will have no money to buy food,” Col. Portento said in English and Filipino.

“The child victim trusts the facilitators [because they are their parents], so it’s easy for them to be enticed to perform or do whatever was requested by the foreigner [in exchange] for a certain price,” she added.

While OSEC also occurs prolifically in other impoverished countries such as Mexico and Romania, pedophiles have discovered that it’s easier to conduct business with Filipinos because of their fluency in English. It’s almost rare to find a Filipino pedophile, Col. Portento said, speaking from her experience that the clients are almost always foreigners.

“Our proficiency in the English language makes it easier for them to engage with both the facilitators [here] and the victims,” the police officer said.

Another factor why OSEC has become rampant in the Philippines is the Filipinos’ poor understanding of children’s rights. While showing naked children to absolute strangers may sound shocking to other nationalities, some Filipino parents think that there’s nothing wrong with it because the pedophiles are not meeting the children. From the parents’ perspective, a child is only being violated if she is being touched.

“They think that there’s [nothing wrong because there is] no touch, [therefore there’s] no harm, no conception,” Estabillo, the social worker, said. “[They think that it is fine because] the children are not being touched. They won’t get pregnant unlike when they are sexually abused [or] when they are raped.”

“Some of them say, ‘They will just perform, they will just dance naked in front of a webcam. Their customer is overseas; they won’t touch the children.’ For them, what they are doing is okay,” she added.

Willing Victims

But parents profiteering off their children’s bodies is just one aspect of the crime. Some teen victims have willingly sold their own photos and videos to foreigners without their parents’ knowledge, said Pamela Uy, the Deputy Executive Director of Bidlisiw Foundation, a Cebu-based charity that works with OSEC survivors.

Teens who do this often come from dysfunctional families. The victims have also suffered through years of sexual, physical, or emotional abuse in their own homes. Or at the very least, they are simply neglected by their parents, who are far too busy taking care of younger children sired from multiple relationships.

Besides, Filipino culture has grown increasingly materialistic, and the cash-strapped teens are intent on keeping up with their peers, even if that means getting exploited in the process, Uy said.

“As adolescents they see their friends having new blouses, dresses, cell phones. They become envious so they look for means to raise their own money,” Uy said.

One of the victims Uy had worked with is Jake*, who used to sell lewd images to men he would meet on gay dating sites when he was about 15 years old.

Engaging in such an exploitative activity was not just a way for Jake to make money. It was also his escape from a troubled home. His parents had separated when he was just a child, and both his mother and father have remarried. Jake hardly knew his father — the first time he “spoke” to him was two years ago, on Facebook Messenger.

“My parents are physically there but emotionally, financially, and mentally, [they were] not there [for me]….[And] my mother is a drunkard. We always argue,” he said.

Living in an impoverished community, with a mother whom he always disagreed with, was tough on Jake. His mother, who had to take care of her younger children by her second marriage, was too consumed by her life to spend time with him. Hanging out and having fun with his friends was his escape.

It was through his friends that he first learned about the business of selling naked photos to foreigners. In Cebu, teens were getting about US$20 to US$50 for each photo they sold. It wasn’t a lot, but for a Filipino boy without means, it was a fortune.

At 15, Jake started befriending people on chatrooms catering to gay men, where he sold his photos to anyone interested. He was a hit: men would shower him with compliments and he was paid for his images.

“I saw my friends doing it. I became curious. I kind of [wanted to earn some cash],” he said.

It was on one of these chat rooms that he got to know one of his clients better, a 47-year-old Caucasian. Through several months of chatting, he and Jake built a certain rapport, and the middle-aged foreigner suggested they meet in Cebu.

Jake was anxious, but he agreed to rendezvous with his client at a hotel and even dragged a friend along. When the duo saw the client from afar, Jake got spooked by what he saw. The man was far older than 47 years old, and he did not look like his photo. Jake and his friend literally ran away from the hotel. Jake never reached out to the man again.

“That was my first time [to meet a client]. I got scared because he was very old. I saw him just once,” Jake said.

The selling of child sexual abuse materials becomes the jump-off point to prostitution, Uy told Coconuts. Like Jake, some of the teens end up seeing their clients and they are lured into having sex with them.

“They actually meet face to face about after two months [or] a few months of chatting when they already get the trust of the child. They get to meet, and then they will bring the child to a fancy restaurant. And then they will check in to a hotel. That’s it. And I think something happens there. From there I think, and I also believe, that they would take videos [of them having sex with the child],” Uy said.

The enormity of the problem at hand became clearer in January this year when a Filipino senator reported that there were teens who were selling their lewd photos online so they could raise money to buy gadgets, now considered a necessity for distance learning.

This raises the question: When OSEC is being used as a lifeline by countless Filipinos to survive, can the government manage to eradicate the problem, or at least mitigate it?

Save the Children

The Philippine government has had some significant wins against perpetrators in recent years. One of its most celebrated convictions was that of American David Timothy Deakin, a Pampanga province resident who was found guilty of trafficking children and selling their lewd images to pedophiles in May 2020.

In addition to that, the local Department of Justice recorded 28 OSEC convictions from January 2018 to December 2019. Meanwhile, the police force has arrested 18 suspects from January to November 2020. Despite these achievements, challenges remain.

In the Philippines, there is a need to identify and capture suspects who offer children to pedophiles. At the same time, foreign governments should come up with laws that impose higher sanctions on their citizens who were found guilty of OSEC.

At present, it’s almost impossible to capture Filipinos who peddle children online because of the nature of IP addresses in the country. Local internet is stuck with IPV4, a system where an IP address is shared by entire villages. What makes it even worse is that the IP address is dynamic — it can change each day.

Colonel Portento of the police force also laments that many ISPs have yet to develop and employ a filtering system that prevents perpetrators from accessing child sexual abuse materials from the web.

“[T]hey have to put in place filtering and blocking devices so that these illicit materials which exploit children no longer circulate [on the web]. But as of this time they still don’t have that in their system,” she said.

The internet service companies that Coconuts contacted for this article declined to sit down for an interview, with the sole exception of PLDT, the company that also owns Smart, another ISP.

Angel Redoble, PLDT’s Chief Information and Security Officer, said that the company is already in the process of migrating to a more sophisticated IP address system, one that would identify the specific location of a user. However, this migration would take some time.

“There has already been an IP version 6 deployment. But it’s very minimal because it has to be done in a very organized and systematic manner so that people will still have access to the internet. Because not all sites [on the internet] are using IP version 6. [The] majority of the sites are still using IP version 4,” he said.

“We are hoping that by 2021 we should already see a significant number of our subscribers using IPV6,” he added.

Redoble also promised that PLDT and Smart will soon have a filtering mechanism that would stop users from accessing websites that host child sexual abuse materials.

“We are subscribing to the Internet Watch Foundation and they already accepted our application so that we will have access to their database of websites containing child porn-related materials, whether photos or videos. Once we have that, we can already [filter websites],” he said.

Redoble added that PLDT has developed a mechanism where “if there’s a user trying to access the website that contains this child porn material, that user will be redirected to a technology…and that content that person is trying to access will be blocked.”

Experts say, however, that OSEC cannot be solved by catching perpetrators alone. Lawyer Sam Innocencio, the national director of the International Justice Mission, which assists the police force in solving OSEC cases, encouraged foreign governments to do their part. He said that overseas, pedophiles just get a slap on the wrist, while Filipino perpetrators spend their entire lifetimes paying for their crimes.

Innocencio said that foreign governments should ensure that their citizens receive stiffer penalties, similar to the ones given to Filipinos.

“Countries, where online sexual exploitation of children is an emerging problem, can work with the Philippine government to replicate the latter’s response,” he suggested.

“As for demand-side countries, one way they can collaborate with the Philippine government is to ensure that perpetrators on their side are held accountable through appropriate sentencing. Another is improved evidence and intelligence sharing between these countries and the Philippine government. This will facilitate increased law enforcement detection and disruption of demand-side online child sex offenders,” he said.

Innocencio said that going after perpetrators — both from overseas and here in the Philippines — is even more important now when most children are forced to stay inside their homes because of the pandemic. The children may be safe from COVID, but they have become unsafe in their homes, where perpetrators can easily exploit them.

“It just created the perfect opportunity for criminally-minded traffickers or sex offenders to abuse children online considering that they have more access to children because they are confined in their homes,” he said.

“There are less barriers to detection because the victims have less access to members of the community like their teachers. Vulnerable children are now stuck at home with their abusers,” he said.

Video credits:

This story was funded through a grant from the International Women’s Media Foundation.