They talked about closing Boracay for months. On Wednesday, the talk became reality.

President Rodrigo Duterte’s spokesperson, Harry Roque, told reporters that the president had ordered a 6-month total closure of the Philippines’ most popular island destination, following a proposal from the departments of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), Tourism (DOT), and Interior and Local Government (DILG).

As of April 26, barely two weeks away, non-residents will be barred from visiting Boracay, a move that will grind the entire tourism-dependent community to a halt.

“You go into the water, it’s smelly. Smell of what? Shit,” Duterte said about the island in February. And while he was exaggerating, yet again, the tough-talking president’s words weren’t entirely wrong.

Boracay is arguably the most popular of the Philippines’ beaches because of its white sand, blue waters, and 24/7 parties that have foreign backpackers and locals alike flocking to it every year. But it’s also been accumulating environmental problems ever since it first surged in popularity in the 1970s.

An underdeveloped sewage system, haphazardly developed land, and terrible waste management are just a few of the problems that have been worsening through the years.

Now, with the closure date looming, there is a black cloud hanging over what was supposed to be a roaring summer season on the “best island in the world.”

Many living and working in Boracay say that while they’re happy the government is finally addressing their problems, a six-month closure could cost them everything.

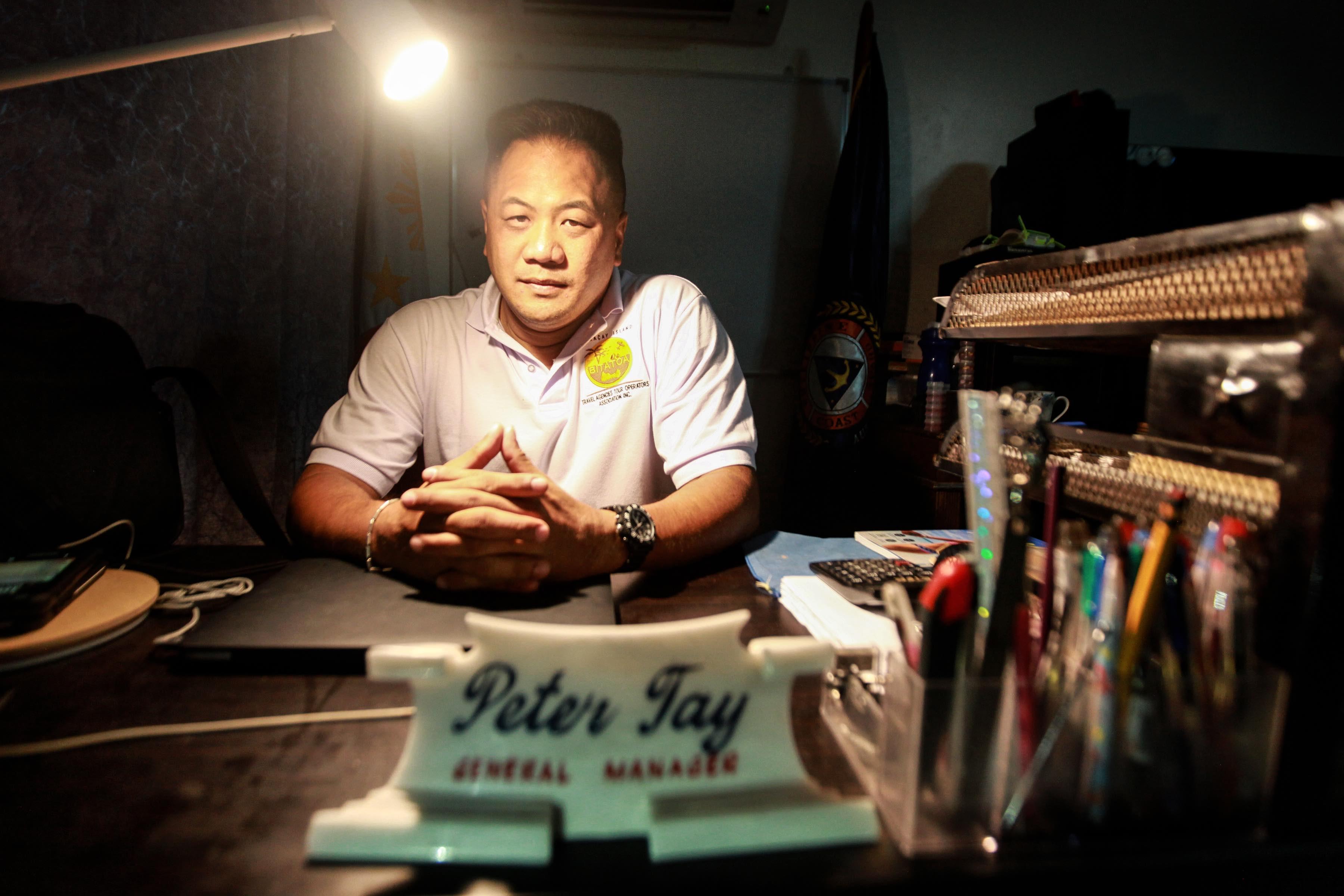

“I think they are in a depression,” Peter Tay, a board member of the Boracay Foundation and the Philippines’ Tourism Congress, said about the island’s residents. “Because imagine, most of them… they rely on this island to make money, to make a living, to support their family, to have food on the table. And suddenly, this is taken away.”

Tay is a Singaporean diving instructor who owns a travel agency in Boracay. Coconuts Manila spoke with him last month while he was in Manila for a few days. He was flying back to Boracay that afternoon, the island that has been his home for 10 years.

During the conversation, he recounted just how much has changed since he moved there in 2008.

“There was no Starbucks in Boracay before. Now we have Starbucks. We even have City Mall. We even have a movie theater. We even have McDonald’s, KFC,” Tay said. “So if you are talking about Boracay island, it’s no longer an island, it’s Boracay city.”

It’s also a far cry from the pristine virgin paradise it was just 40 years ago.

Killing the golden goose

“They’re killing the goose that lays the golden egg… It’s very cliche, but the people in Boracay, including the government, they are racing to profit from Boracay until the very last breath,” Vince Cinches, the oceans and political campaigner for Greenpeace Southeast Asia, told Coconuts Manila last month.

For him, the desire to capitalize on its beauty is the very reason the island has been deteriorating.

Everyone wants a piece of Boracay — tourists, the government, and businesses included. In 2016, 1.7 million tourists visited the island.

The sheer level of commercialization can be overwhelming from the moment you step off the plane. Posters selling everything from telco companies to credit cards are plastered on seemingly every inch of wall or hung as streamers at the port. The hundreds of hotels, restaurants, and bars crammed onto the 1,000-hectare island brings to mind a sandy strip mall.

In February, the DENR found that at least 842 establishments were in violation of the Clean Water Act and the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act. Thanks to a lack of infrastructure, many of them can’t connect to the sewage system and end up dumping wastewater into drainage canals that directly lead to the sea. Unsurprisingly, recent studies have shown the water offshore to contain high levels of coliform bacteria.

And then there’s the garbage.

“[T]here’s just so much plastic and disposable single-use waste that happens on the island, and there’s a dump at the back of the island that doesn’t get carted away,” licensed environmental planner Mark Evidente said. He also acts as the legal counsel for the Tourism Congress and helped draft the Tourism Act of 2009, which was intended to address ecological as well as social concerns.

Last year, 20,000 cubic meters of waste were hauled away from a recycling facility in Boracay and moved to the Aklan province mainland after the DENR threatened to file criminal cases against local government officials.

Trash cans are also severely lacking on the main strip, which leads to tourists leaving trash just about everywhere.

Both these problems, however, flow from the larger issue of overdevelopment.

“Development happens left and right. Some legal, some illegal… and because of that unregulated development, all these problems of crowding, waste are compounded,” Evidente said.

For Cinches, this unregulated development was brought about by the government’s failure to implement existing laws.

“LGU (local government units) is just doing nothing, so they need to clearly pursue their mandate as a local government under… the local government code, being at the forefront,” he said in English and Filipino.

“That means [implementing the] building code, the implementation of the Solid Waste Management law, Clean Water Act, it needs to happen. There should be no nonsense implementation of our laws.”

Just last month, as the government considered Boracay’s closure, it was announced that a casino-resort from Macau’s Galaxy Entertainment was to be built on the island in 2019. Yesterday, Duterte said he knew nothing about the project but a photo from the Malacañang Palace shows that the president met with the casino company’s executives 4 months ago.

A few before that, another company announced plans for a 1,001-room hotel that would be the largest hotel in the Philippines in terms of capacity.

Cinches suggested that Boracay’s problems could have been prevented if only regulatory bodies like the DENR were on top of things from the beginning.

“You have DENR, who failed their mandate. [What they’re doing] is such a knee-jerk [reaction],” he said. “It’s good that the DENR is now doing something, but they should recognize that this problem has been known by the regulatory agency for so long.”

That’s a take that’s rejected by DENR Undersecretary Jonas Leones, who insisted that the government has actually been trying to fix Boracay’s problems even before the Duterte administration.

In a recent interview with Coconuts Manila, Leones explained that the government has gotten rid of establishments that violate easement zones in the past, but that they eventually just set up shop again.

“These are the major problems that we can’t solve if we don’t stop the increase of tourists first. So we need to kind of temporarily close [Boracay] so we can fix these major problems,” he said in Filipino.

Leones added that the island’s complete closure is necessary to, once and for all, solve Boracay’s problems. In the six months it’s shuttered, the government plans to do a complete overhaul — from cracking down on construction encroaching on forest lands, to installing sewer lines.

Doing a partial closure, Leones said, would only serve to inconvenience tourists and pose potential safety risks.

But for most who actually live and work on the island, the closure is much more than an inconvenience.

‘We’re just street vendors’

35-year-old Junrey Coching Tampos is what one might call a true Boracaynon.

He was born on Aklan’s mainland, was raised on the island, and still lives there today. His mother, Merlita Coching Tampos, hails from the indigenous Visayan group known as the Tumandok and claims to have invented the chori burger, a street food item now found in barbecue stands all over Boracay that hungry late-night party goers are all too familiar with.

Junrey has been helping out in the family business since he was 7 years old and continues to manage it today. Life on the island is all he knows and he’s afraid of what might happen when the closure starts.

“[W]e’re just street vendors. Our earnings are meager,” Junrey told Coconuts in Filipino last month. “It’s just enough to buy our basic needs. But when it comes to savings, we have nothing.”

For environmental planner Evidente, this has implications the government can’t afford to ignore.

“A lot of workers in Boracay are classic isang kahig, isang tuka (from hand to mouth) workers,” he said.

Junrey’s barbecue stall has a daily gross of about PHP3,500 (US$67.20), much of which he uses to buy supplies for the next day. What’s left over is shared among five other family members.

Estimates from the municipality of Malay, Aklan, where Boracay is located, show that as many as 30,000 workers stand to lose their jobs during the six-month closure.

On Wednesday, Senior Deputy Executive Secretary Menardo Guevarra said that calamity funds would be used to help displaced workers, but specific measures have not been released, causing worry among those, like Junrey, who don’t have nearly enough money saved to tide them over for half a year.

This is why for Evidente, a phased closure of the island would have been better.

“Look, everyday, roads are being repaved, right? Without having to close entire cities,” he said. “I would think, instinctively, that a phased approach or a phased closure is always better than a total closure. Because it allows people to adapt.”

The problem, he said, is that not nearly enough stakeholders were consulted before the decision was made.

“I have not heard… of a very comprehensive consultative process with the residents of the island, the investors, and business people of the island. With tourists who go to the island,” Evidente said. “Who is really being consulted? Because a lot of these inputs on what people would like Boracay to be should be more than what a few decision-makers have in mind.”

Tay, the travel agent, had the same concerns, saying he and his fellow agents were not consulted before the closure was proposed to the president.

“We don’t have an idea what is going on, because the government never, never consult us,” he said. “They just make their own decision. Let’s close Boracay six months, 1 year. They never even asked: What do you think? Is there alternative? Can you give us a suggestion? Nothing. They just tell us ‘we will close Boracay’.”

So what would the people of Boracay suggest if they were asked? It turns out, quite a lot.

Differing views

On Wednesday, a week after Coconuts spoke with Junrey, he sent photos of a side street with a message that reads simply: “There’s still no justice.”

The picture he sent is of one of the few passageways that connects the beach to a congested residential area hidden behind two large hotels. He said that the side street, about two meters wide, is used by more or less 1,000 residents every day. It’s narrow because the two hotels on either side went beyond their easement zones.

Junrey and other residents knew exactly how that would play out, leading them to raise concerns with the local government when construction on the hotels began five years ago.

“We already asked for help when they were just constructing the hotel. Even after [construction] finished, no one helped. Until now, it’s all just promises,” he said.

But things have changed, DENR’s Leones insisted, and these are exactly the kind of establishments they want to crack down on.

“The truth is, from the centerline, there should be a six-meter or 12-meter [easement zone] from either side [of the establishment], so that the streets are wide. But when you go there now, everything is cramped,” Leones said, saying he believed the closure can fix these kinds of problems.

But Junrey has decidedly mixed feelings about the government’s plan.

“Yes, [I agree with the closure], so that rehabilitation can be done quickly. Infrastructure will be built quickly, and it will be finished fast,” he said. “No, because a lot of people will be affected, like us — employees or vendors or those whose livelihood are in Boracay. That’s the negative and positive that could happen to Boracay.”

Some Boracay business owners, however, are more full-throated in their approval of the shutdown.

Rheymart Salcedo is a henna tattoo artist from Baguio City who moved to Boracay in 2010, where he had been managing a henna and hair braid stall on a tiny patch of sand in Station 2, the designation for one of three areas on the island’s main tourist strip.

That came to an end last week, when he had to leave his usual post after his landlord decided not to renew his rental agreement because of the upcoming closure.

Despite the island’s shutdown costing him his location, Salcedo said he remains in favor of the move and understands how it could benefit the area in the long run.

“They should continue the closure, and until the problems are solved, it should not open. That’s what I think,” he told Coconuts Manila in Filipino.

“[I]t’s unfortunate for those with businesses, especially small businesses… but if they understand why it will be closed, they should just help and cooperate, because this isn’t for the government. This is for the environment and for tourism.”

What he’s not in favor of is the April 26 start date, just days before Labor Day weekend or “LaBoracay,” when droves of tourists usually fly to the island to attend some of the biggests summer parties.

“Off-season here is June,” he said. “[The closure is] too early. It’s unfortunate for those who have not saved up.”

The National Economic and Development Authority actually suggested earlier that the closure be done during the lean season, but Duterte still opted for an earlier start date.

Salcedo partly owns six other henna tattoo stalls in other parts of the country and acknowledged that while the closure will be difficult for him, he’s more privileged than others who have no choice but to stay in Boracay.

An uncertain future

Just as people’s ideas for reviving the island vary, so do their visions of Boracay’s future. Some, like Tay, don’t mind welcoming new development as long as it’s managed properly.

“There’s nothing we can do to stop the change. Why go backwards?” he said. “[So] we move forward, and make it into a… world class destination, in terms of the roads, in terms of the infrastructure. [We] protect the environment and do everything to care for the environment.”

Evidente, however, believes that there’s a need to scale down, not just on development in general, but even the number of people visiting the island each year.

“For me, it would probably really involve bringing down the number of people on the island, setting a cap on the number of hotel rooms,” he said.

He rattled off popular global destinations like Barcelona and Machu Picchu, which have set limits on the number of people who can visit the area by limiting the number of hotel rooms and going after unregulated AirBnBs.

“If we truly believe that Boracay is like the jewel in our crown, then we have to take serious measures,” Evidente said. These measure could include prohibiting single-use plastic containers and making use of renewable energy throughout the island, he suggested.

With barely two weeks until the closure, the one long-term vision for Boracay that no one seems certain of is the government’s.

Whatever that turns out to be, one thing is certain: For better or worse, it’s not going to be the island you once knew.