Kuala Lumpur’s RM4 million blue bike lanes (US$1,015,000) have done the unthinkable, they’ve got the city’s cyclists, motorbike riders, and drivers to all agree. Unfortunately, the one thing all three groups agree on is that they kinda suck.

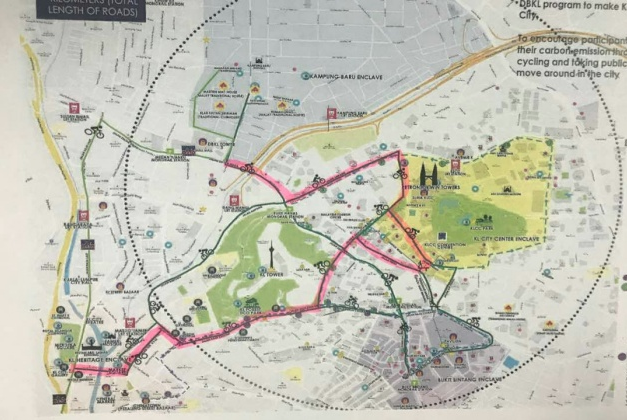

Less than a month after City hall (aka the DBKL for our non-Malaysian readers) debuted 5 kilometers of bright blue-painted bike lanes that run alongside some of the city’s main roads, it appears everyone has an issue.

Cyclists are claiming that the lanes are not only inconvenient, but dangerous. Motorcyclists have been injured by raised dividers separating road from blue lanes, and the DBKL was forced to hastily remove the dividers. Car drivers, meanwhile, don’t seem to have gotten the memo that the lanes are to be kept clear for cyclists, and have been widely using the lanes as convenient new spots to double park their vehicles.

A video shot by cycling coach Kenny Kwan two weeks ago was the first indicator that something had gone amiss. The former national cyclist was appalled not just at motorists’ ignorance, but more so at what he sees as the deeply flawed nature of the project.

He believes that a far more practical approach for a city like Kuala Lumpur with such little cycling culture would have been to create a parallel lane that would run alongside the pedestrian pavement, as the blue lane is often too narrow to be safe. He added that the lane as currently set up could actually be dangerous for cyclists to use, particularly during peak hours.

Compounding the problem is the fact that little regard was given to traffic flow, Kwan explained. He characterized it as inconsistent. In some sections, bikes are expected to move against the flow of traffic. In other sections, there are two lanes on each side of the road.

Bike lanes are always supposed to be on the left side of the shoulder, he added, but KL’s bike lanes flip-flop between left and right depending on where in the city you happen to be cycling.

If Kwan’s laundry list of faults doesn’t already have you cringing, he adds that several intersections don’t link up, with the bike lane simply becoming part of the sidewalk at certain points, making it dangerous for both cyclists and pedestrians.

He also cites KL’s first bike lanes that run from Mid Valley to Dataran Merdeka, at times sharing lanes with congested traffic in one of the city’s busiest neighborhoods, Brickfields. At best, one could call the paths under-used. In the eyes of avid cyclists like Kwan, they are redundant, and make little sense as they do not link up with the newer lanes.

The lanes were introduced in conjunction with the city’s hosting of the Ninth World Urban Forum (WUF) from Feb. 7 to 13, with City Hall officials hoping that visiting participants would be able to use the lanes while traveling between conferences, city attractions, and their hotels during their stay.

So far, five kilometers of lane have been painted, with city officials aiming for 11 kilometers of usable path within the next five years. The hasty removal of lane separators, 50-millimeter-high dividers that have resulted in bloody injuries, was an early sign that the city had not foreseen issues that many cyclists thought were obvious.

Jeffery Lim, project coordinator for Cycling Kuala Lumpur, and Bicycle Map Project, pointed out that while the dividers separated fast-moving vehicles from bikes, their solid metal design could be fatal to riders, drivers, and pedestrians.

“There are concerns, of getting caught and falling, there are also concerns of encroachment and causing hurt or fatality to the non-motorized vehicles or pedestrians due to encroachment by motorized vehicles,” he said.

DBKL later consulted with the local cycling organizations, and the dividers were removed and replaced with soft, orange poles. It’s a start.

Urban cyclists agree that one factor is key in making the city’s dream of a bike-friendly city a reality: an educated public.

Amar Zainal, a city-center worker who regularly commutes to his office via bike and public transportation, says that even the most established buildings in the city have zero bicycle parking. Motorbike spaces are ample, yet there is nothing you can chain your bike to.

This lack of regard for cyclists extends to a wider apathy by Malaysia’s car-centric populace, he says. “Not just to cyclists, but to motorcyclists, pedestrians, and each other.”

Kwan, for one, hopes that the city’s new focus on bike lanes will be accompanied by an education campaign for a public that is largely aware of how to properly abide by the rules. More stringent traffic fines for motorists behaving badly will be necessary if that campaign fails, he added.

One thing is certain: The hot-button issue’s future is still very much up in the air.

Last week, the city’s mayor Tan Sri Mohd Amin Nordin Abd Aziz spoke at the official unveiling of the bike lanes, saying that they would most likely require a re-audit. Grand opening! Grand closing!

Mohd Amin cited the lanes on Jalan Raja Laut as being problematic, namely because it’s a one-way street flanked by two bike lanes.

One solution he offered was removing the left lane, to make room for buses. For the record, that goes against the recommendation of urban cycling planners, who — like Kwan — recommend a left lane bike path. Just throwing that out there, free of charge, DBKL.

However, any concrete decisions will only take place after a full audit, which the mayor believes can take anywhere from one to two months.

Cool. No rush. Since you’ve got RM4 million behind this project, may we suggest consulting some professionals, who have done this before, in some of the world’s most bike friendly cities? Get them in a room with Kenny Kwan.

Our calls to City hall on the issue were not returned (free advice still there for the taking, guys — no hard feelings).