A Nobel Prize nomination entry number 48-0 may be not mean much, but for Malaysia its a mark of honour, as it was held by the country’s — or more accurately Malaya’s — first Nobel Prize nominee, Dr. Wu Lien Teh. Here’s a look at his work.

A school located on a road called “Love Lane” would catch anyone’s attention. What more if the school started out as a “free school”, opening its doors to all who wanted an education.

This is Penang Free School, a famous institution — worthy of a story of its own — that has produced top students who have gone on to make a name for themselves and their country.

These high-calibre individuals include Malaysia’s first Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman, judge Eusoffe Abdoolcader and iconic entertainer P. Ramlee.

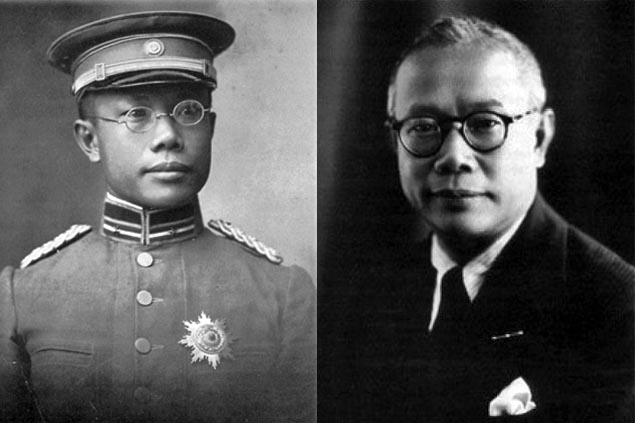

Many Penang Free School alumni went on to be highly regarded medical practitioners, but only one received the world’s highest accolade as a Nobel Prize nominee, Penang-born Dr Wu Lien Teh. He received the nomination for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1935.

The Nobel Prize was created in 1900, after a decision to recognise worldwide achievements in science, physics, medicine and peace. It was the result of long-drawn negotiation and conflict over the late Alfred Nobel’s will in 1895 which was to leave much of his wealth towards this prize.

Part of the will read that his estate should be used to endow, “prizes to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit to mankind.” His family opposed, but after much legal tussling and negotiation, the first prize was awarded five years later.

According to records from the Nobel Foundation, Dr Wu was nominated by Professor W W Cadbury from Canton University, for his “Work on Pneumonic Plague and especially the discovery of the role played by the Tarbagan in its transmission,” under nomination no. 48-0. This was amongst the 177 nominations received in 1935.

Dr Wu did not win the award, but it was a honour just the same to grace the Nobel Prize boards with his contribution to medicine. Fun fact, Professor Cadbury is related to the founding family of Cadbury chocolate.

Dr Wu was originally known as Ngoh Lean Tuck and changed his name to ‘Wu Lien Teh’ when he travelled to China in 1908. He began his journey into medicine after winning the Queen’s Scholarship and gaining admission to Cambridge’s Emmanuel college in 1896, while moving to St Mary’s Hospital in London to spend his undergraduate clinical years.

Researchers following his work speak highly of Dr Wu’s achievements: “Although standing at only 5 feet 2 inches, short even by Chinese standards, he towered over many of his contemporaries because of his dedicated medical work,” as reported in the 2014 Singapore Medical Journal (SMJ) written by Kam Hing Lee, Danny Tze-ken Wong, Tak Ming Ho and Ng Kwan Hoong.

What did Dr Wu do to gain him such high praise?

Well, for starters, he was instrumental in the fight against opium. Having travelled to China and back to Malaya, he was attached to the Institute of Medical Research, but was concerned with opium addiction, particularly high amongst Chinese working class. He founded the Anti-Opium association in Penang, and organised a conference attended by 3,000 people.

Something ironic happened then. According to the SMJ research, Dr Wu was charged and fined in court for possession of an ounce (about 28g) of opium tincture in his clinic.

“In his defence, Wu claimed that the cupboard in which the drug was found came with the clinic he had bought from a British lady doctor,” said the research, adding that it was unclear if this case had to do with his fight against the drug.

After opium, Dr Wu contributed to China after setting up practice there. A health crisis occurred where hunters were being exposed to ill marmots, and beginning to contract a deadly disease, the pneumonic plague.

It started to infect hundreds of people, even some medical practitioners in Harbin, China. Dr Wu took on radical approaches to deal with this disease to prevent it from spreading. After finding over 2,000 unburied bodied infected with the diseases, Dr Wu was worried.

“Mass cremation was the solution, but the Chinese viewed this as an act of desecration,” according to SMJ. Dr Wu appealed to the Emperor and finally cremation was allowed to stem the problem. The epidemic lasted seven months.

Dr Wu himself was the subject of danger, as he was detained and questioned by the Japanese during World War II, on allegations that the doctor was a Chinese spy. He was also caught by the resistance movement in Malaya, but later released. He escaped captivity due to his medical credentials and also had served as a physician to one of the Japanese officers in Malaya.

Researchers note that Wu gained gained international fame when he helped bring the Manchurian plague under control. “More importantly, Wu brought with him an outsider’s perspective, free from the tradition of China’s medical practices, but as an overseas Chinese, he stood with China’s quest for modernity through western medicine,” said the report.

Dr Wu’s work is celebrated and documented by his family and historians from the Dr. Wu Lien Teh Society in Penang.

Set up in 2013, it promotes and support activities that advance the legacy of Dr Wu Lien-Teh and ensure credible documentation pertaining to his life. Dr Wu’s great grand niece, Alison Chong works on documentation and building the Wu family tree.