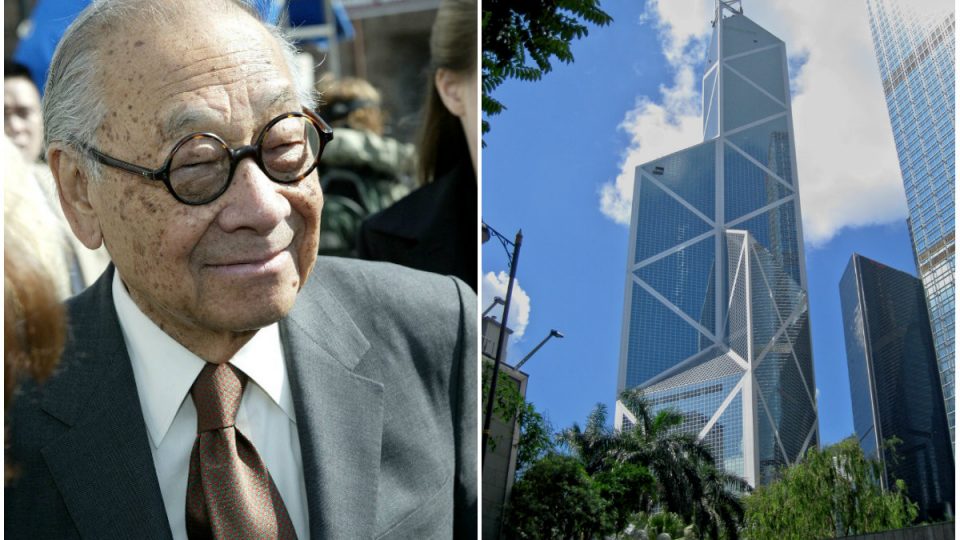

Chinese-American architect Ieoh Ming Pei — who designed the iconic Bank of China Tower in Hong Kong and Louvre pyramid in Paris — turned 100 years old today.

Pei, who was born in Suzhou in 1917, grew up in Hong Kong and Shanghai before moving to the United States, where he obtained a bachelor’s degree in architecture from M.I.T. and master’s from Harvard’s Graduate School of Design.

After a stint designing bombs at the National Defence Research Committee in the 1940s, Pei taught at Harvard for a few years before joining real estate development firm Webb and Knapp, where he completed his first architectural project; a corporate building at 131 Ponce de Leon Avenue, Atlanta.

Over the decades, Pei began taking on more and more projects of increasing importance, before he was eventually asked by then-French president Francois Mitterrand to help renovate its iconic museum, the Louvre, in the 1980s.

While Pei, then in his mid-60s, was already an established star in the U.S. for his elegant John F. Kennedy Library and Dallas City Hall, nothing had prepared him for the hostility his plans for the Louvre would receive.

One meeting with the French historic monuments commission in January 1984 ended in uproar, with Pei unable even to present his ideas.

“You are not in Dallas now!” one of the experts shouted at him during what he recalled was a “terrible session”, where he felt like the target of anti-Chinese racism. Not even Pei’s winning of the Pritzker Prize, the “Nobel of architecture” in 1983, seemed to assuage his detractors.

The museum’s then-director, Andre Chabaud, resigned in 1983 in protest at the “architectural risks” Pei’s glass pyramid vision posed, and up to 90 percent of Parisians were said to be against the design before it opened in 1989.

“I received many angry glances in the streets of Paris,” Pei later said, confessing that “after the Louvre I thought no project would be too difficult.”

The Louvre’s current president, however, is in no doubt that the pyramid is a masterpiece that helped turn the museum around. For Jean-Luc Martinez the pyramid is “the modern symbol of the museum”, he said, “an icon on the same level” as the Louvre’s most revered artworks “the Mona Lisa, the Venus de Milo and the Winged Victory of Samothrace”.

Concurrently, Pei had been contracted by the Chinese government to build a new tower for the Bank of China in Hong Kong, prior to the 1997 handover. While he was averse to the idea of designing a nondescript skyscraper, experimentation quickly led Pei to creating what is now easily the most recognizable skyscraper in Hong Kong.

While the tower invited some controversy during the planning stages for bypassing the normally essential feng shui consultation and integrating apparently inauspicious design elements, minor adaptations were appease prominent feng shui masters.

The reflective geometrical facade, said to be inspired by bamboo shoots, has since become synonymous with Hong Kong and a landmark in its own right. While we like to think that everyone makes their mark on the city in some way, I. M. Pei has left an impact on Hong Kong that most people could never even imagine achieving. Happy birthday, Mr. Pei.

Words: Coconuts Hong Kong, with reporting from AFP