Away from the main roads in one of Hong Kong’s oldest districts, the streets lie silent.

The shutters are down on rows of car mechanic shops, once a thriving business in the working-class neighborhood. Tarpaulin and bamboo scaffolding hide the facades of time-worn, dilapidated mid-rises dating back to the 1950s.

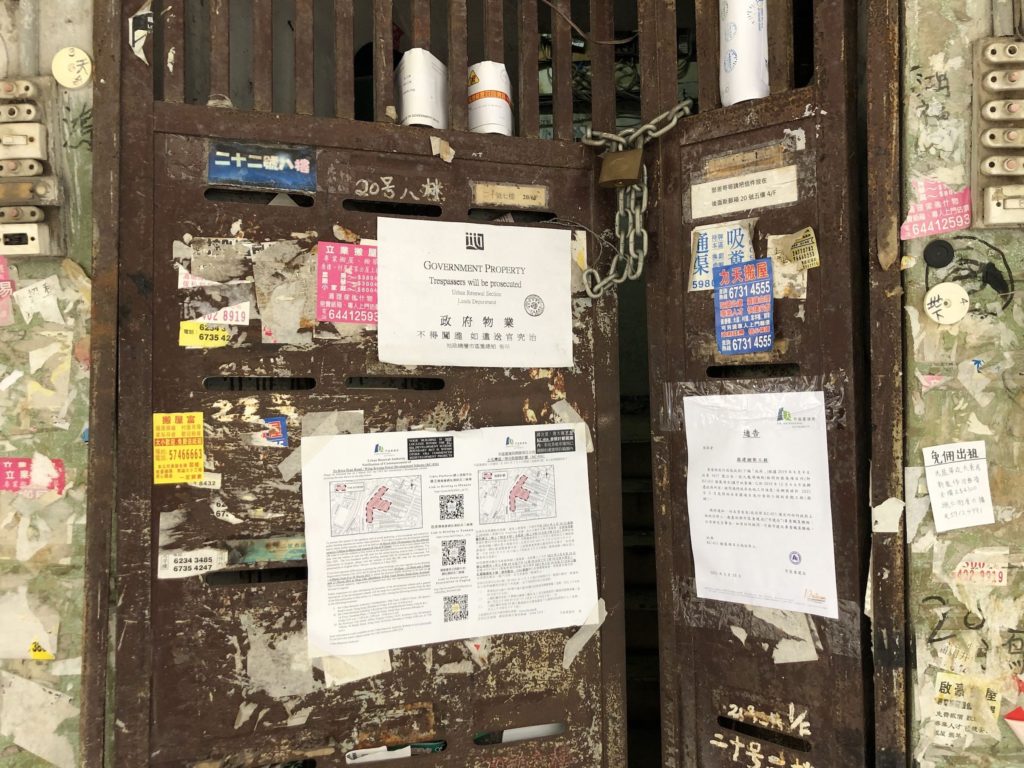

Block after block, legalese-laden notices are taped to already-closed shopfronts and vacant buildings. They’re letters from the Urban Renewal Authority (URA), the quasi-government body spearheading large-scale redevelopment in To Kwa Wan.

On a May morning, Ah Long—who has lived in To Kwa Wan for over 30 years—leads four people on a Sunday tour, organized by a district concern group called House of To Kwa Wan Stories. Also known as To Home, the group hopes these weekend tours can show Hongkongers a glimpse of the neighborhood before it’s too late.

Following Ah Long into a tenement building, the tour group shuffles past the stairwell and the rusted mailboxes, standing shoulder to shoulder in the cramped space.

Ah Long gestures at the electricity meters, one for each subdivided home in the building. “This is how you can tell if the homes are vacant or still occupied,” he explains. “If the metal disc in the meter is barely rotating, the home is empty.”

Fond farewells

Located in eastern Kowloon, To Kwa Wan—home to a concentration of factories during the city’s manufacturing heydey—is a district untouched by the gentrification that has swept other parts of Hong Kong.

Today, self-service laundromats, hardware stores and express salons promising haircuts for HK$50 (US$6.50) line the blue-collar neighborhood. There are no glitzy skyscrapers reflecting the morning sun, and no Starbucks to grab a mid-day coffee.

This is the To Kwa Wan that residents and business owners know and love—but times are changing.

“We’ve been farewell-ing people non-stop,” Tjhan Shui-ling told Coconuts during an interview at To Home’s space on Hung Fook Street. The 28-year-old is the group’s Community Organizer.

According to the URA, there are currently nine redevelopment projects in To Kwa Wan. By area, the largest is an L-shaped enclosure comprising four side streets, from which almost 1,000 households had to vacate.

“Before, around this time in the afternoon, kids will start being let out from school and they would come [to To Home]. We’d have three or four kids surrounding us, tugging and talking to us,” Tjhan said. “We’d help them with homework and just listen to them rant. Their moms will come to hang out too.”

![The red characters read “Cheung Hing Chicken [and] Duck.” In a former life, the unit that To Home now occupies was a live poultry shop where chickens and ducks would be slaughtered on the spot for sale. In 2008, due to the bird flu outbreak, the government banned the stocking of live poultry in retail outlets. Photo: Coconuts Media](https://cdn.coconuts.co/coconuts/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/to-kwa-wan-to-home-interior-1024x768.jpg)

There’s a train a-coming

To Kwa Wan’s redevelopment revolves around the district’s new MTR station, set to open end of June. The Tuen Ma line station is part of the Sha Tin-Central link, the most expensive rail project in the city’s history, and will bridge the northern New Territories and Hong Kong Island.

Slowly but surely, gentrification has begun to rear its head, with shiny developments now standing among rows of faded mid-rises. (The neighborhood’s old buildings were subject to height requirements due to proximity to the former Kai Tak Airport.)

Bearing chic, modern-sounding names like City Hub and Downtown 38, the apartments boast clubhouses with gyms, swimming pools and other amenities. In line with property trends in the city, most of the new units are studios and one-bedrooms.

“Sales [for the properties] have been quite enthusiastic,” Lawrence Lam, Chief Assistant Associate Sales Director at a Midland Realty branch in To Kwa Wan, told Coconuts.

Explaining the demand, Lam said the neighborhood is in a prestigious school catchment net with some of Hong Kong’s most coveted primary and secondary schools, making it attractive for families with children.

He added: “Even without the MTR, transportation to other parts of Kowloon is also good. There are many buses and minibuses to Yau Ma Tei, Tsim Sha Tsui and Mong Kok.”

But for the average To Kwa Wan family, moving into these apartments is but a pipe dream. At City Hub, just opposite the MTR station, the average price per square foot is over HK$20,000 (US$1,240), transaction records from Squarefoot show—higher than the average property price per square foot in Hong Kong.

No public housing will be built in the To Kwa Wan redevelopment areas, the URA told Coconuts. Land in nearby Kowloon City, where there are two ongoing projects, has however been earmarked for public housing development with a target completion year of 2031.

With the MTR opening soon, many expressed concern that prices are already rising.

For Wasal Khan, life doesn’t venture far from a buzzy intersection at Ma Tau Wai Road and Wing Kwong Street. He moved into an apartment there seven years ago, and in 2019, opened a small shop just downstairs stocking South Asian snacks.

“[Business] is good,” said the Pakistan-born Khan, whose shop caters to the neighborhood’s ethnic minority community. “But rent is getting more expensive.”

Khan also needs to move as his area is part of URA’s redevelopment zone. He isn’t sure when, but when the time comes, he prefers to stay in the district. “Maybe I’ll move to the wet market,” he added.

A neighborhood time capsule

To Home, too, is counting down the days. The group must relocate by August, and they’re looking for a ground-floor unit like theirs—it would make it easier to greet passersby and form community relationships. But with a limited budget for rent, they haven’t had much luck.

Logistically, they’ll be moving with plenty of baggage. To Home is a hodgepodge of out-of-place furniture and knick-knacks, a result of adopting the fixtures of now-shuttered businesses.

“We’re like a mini museum,” Tjhan said.

Restaurant booth seats, salvaged from two cha chan tengs that closed in 2019, occupy considerable square footage in To Home. One of them had been operating for almost 40 years; the other 12. Above the booths, the restaurants’ handwritten menus hang, their specials of the day forever frozen in time.

“[The almost 40-year-old] cha chan teng witnessed To Kwa Wan’s industrial change,” Tjhan said, referring to the 1980s northward shift of factories to mainland China. “That cha chan teng was quite big because it needed to accommodate all the factory workers who would go there to eat.”

By To Home’s entrance is a glass cabinet displaying soap, hair accessories and spools of yarn. For nearly 60 years, the cabinet sat at the foot of a walk-up building, the shop run by an elderly couple who started the business when they got married in their 20s. With no place in modernized Hong Kong, few such stores—known as “under-stairs shops”—still survive in the city.

“We’ll move all this stuff with us,” Tjhan said. “When everything is closed and everyone is scattered, we still want to have something to show.”