It was almost 5am on Jan. 1 when Prius (not his real name) parked his Toyota Prius (his real car) outside the Police Tactical Unit compound in Fanling and began what he calls his scariest ride.

Three burly men climbed into the backseat. The 43-year-old suspected, rightly it would turn out, that they were police officers. He’d tried to avoid situations like this.

Since starting as an Uber driver in 2016 after career shifts through IT, finance, jewelry sales, and real estate as well as a stint of self-proclaimed slackness, Prius, like several rideshare drivers who spoke to Coconuts HK, had developed his own tactics for evading the cops.

Untalkative riders in pairs who don’t look like friends; inquisitive passengers that probe too much; fares from the airport; recently created accounts with too-perfect approval ratings — these, say some drivers, should be treated with caution.

But, lacking a private hire-car permit, like almost all of the 30,000 drivers Uber says are working in Hong Kong, Prius knows there’s no way to avoid the fact that ferrying passengers for profit could inevitably land him in court.

It already has for several, including 23 people whose case is currently before the court and five people convicted last year, whose acts, a judge ruled, were little different from those of pak pai, or pirate taxi drivers.

So it was with a feeling of nervousness that Prius checked the route on his phone and prepared, with police officers in the car, to break the law in the name of one of America’s largest private companies, valued recently at US$48 billion, for a fare of HK$135.22, about US$17.

“I was anxious, of course,” said Prius, who — fortunately for him – discovered that he had picked up off-duty cops who simply wanted a “cheap ride home,” not undercover officers looking for a suspect.

“But I will take my risks. In Hong Kong nowadays, if you are just following the most legitimate rules, you can’t make the money.”

Risky Business

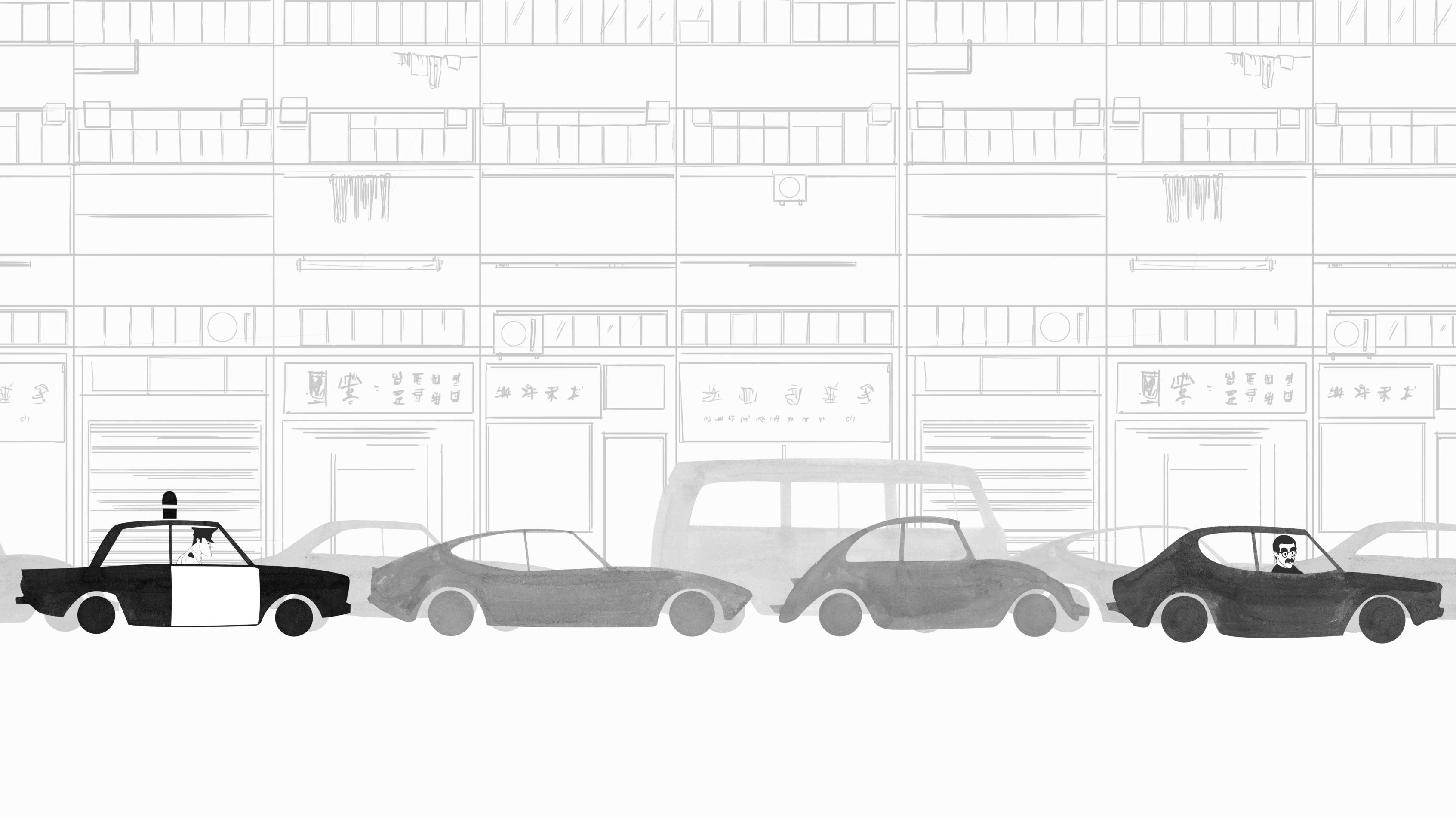

Such are the fears that hover in the minds of the city’s Uber drivers as the US ride-hailing giant hobbles toward four years in Hong Kong.

Denounced by taxi drivers, deemed illegal by officials, yet used by more than one million passengers since its launch, they find themselves in the middle of a debate, but on the wrong side of the law, cautiously completing orders while, this month, prosecutors continue to make their second major case against drivers using the app.

The accused — 22 men and one woman arrested last May in a three-week undercover sting — face potential three-month jail sentences for driving without the necessary permit, an offense that carries double penalties for subsequent guilty verdicts.

Like all Uber drivers, Stephen, 43, is paying close attention.

Previously a part-timer, as are the majority of ride-sharing drivers, the 43-year-old has relied solely on fares for subsistence since January when, unhappy with his career, he resigned from a real estate firm to, as he puts it, sort his life out.

Working mostly six-day weeks, and clocking on for 10- to 15-hour shifts, he can usually earn between HK$800 and HK$1,000 a day after Uber’s 25 percent cut and petrol are factored in, a take he describes as “not too bad” for a risk he’s willing to accept — for now.

With cabbies taking to the streets in protest, and the court decision bearing down, Stephen says he finds himself skipping a day or two on occasion to stay on the safe side, only to go back out when his cash runs low.

Should a harsh verdict be handed down, the already awkward status quo may become too much for many, he thinks.

“Money is the biggest factor,” he says. “Of course, maybe if we are going to be put in jail, I think most Uber drivers will think it’s not worth the risk. But for me, simply increasing the (HK$5,000) fine is threatening enough.”

The Battle for Hong Kong

Uber’s worldwide legal woes are well known.

Created almost 10 years ago, the company has come to exemplify the Silicon Valley credo of “move fast and break things,” clashing with regulators and the entrenched taxi trade in at least 40 countries, amid myriad other controversies.

At the same time, increased competition in the rideshare sector recently squeezed it out of markets in Southeast Asia — where it sold its business to Grab for a stake in the Singaporean firm — and China, where a similar deal in 2016 with its rival, China’s Didi Chuxing, left the latter as the county’s main player.

So it’s on the backfoot that Uber fights to keep its service in Hong Kong, where it’s found public support from many frustrated with the oft-criticized behavior of conventional cabbies, who are regularly reported for overcharging, refusing rides and other bad behavior.

Lobbying for legalization, proponents — including the city’s Consumer Council — have argued competition is urgently needed to improve the sector and spur innovation, with many pointing to the success of ride-sharing in China while lamenting that technology like e-payment services lag behind in Hong Kong.

But despite Chief Executive Carrie Lam promising to “remove red tape” and support a sharing economy during her policy speech last year, officials have steadfastly maintained that private Uber drivers must comply with current regulations and hold a private hire-car permit, the sort held by limousine drivers.

The permits — 648 of which were in use as of July last year — entail strict conditions that make compliance for most rideshare drivers all but impossible.

Researcher Alain Chong, who has studied Uber’s adoption in Hong Kong, sees two main reasons behind the government’s reluctance to embrace ridesharing.

First, the stakes for the city’s taxi industry are high. Capped at just 18,163 and issued in perpetuity, taxi licenses — 60 percent of which are held by individuals and the rest by companies — are traded privately and can fetch premiums of up to HK$7 million (about US$881,000), creating a powerful vested interest authorities appear unwilling to confront.

Secondly, he adds, Hong Kong’s extensive public transport system offers alternatives and alleviates some of the demand that might otherwise force the government to embrace ridesharing.

“Although the technology brings many benefits… [the government] is unwilling to confront or change the current system,” said Chong, a professor of information systems at the University of Nottingham in Ningbo, China.

“At the moment, probably the pressure is not enough to make changes.”

The result, says David S. Lee, a senior lecturer at the University of Hong Kong’s Faculty of Business and Economics, is somewhat strange in both a legal and moral sense.

While infrequent crackdowns targeted at drivers rather than the company suggest there’s little appetite for stamping out Uber’s operations, people working under its brand nonetheless remain in a precarious position.

“It’s a slightly odd situation,” he says.

Disgruntlement

For some drivers, the uncertainty has bred disgruntlement and, often, that’s directed at Uber.

Paul, 44, began rideshare driving three years ago after losing his job at an auto parts company. A car enthusiast with his own ride, he spotted an Uber ad seeking drivers on Facebook and, after things started well enough, decided to go full-time, driving six days a week, aiming for HK$1,200 per day.

The arrangement, though, has soured. Financially, Paul says, he found it difficult to turn a profit on the company’s rates, which, following similar criticism from drivers, were raised last August.

He says his faith in Uber nosedived, however, after a confrontation with two passengers, who threatened to, and eventually did, call the police after complaining about his attitude. Though the officer resolved the situation – and declined to fine him — Paul say his calls to the company’s helpline for drivers were brushed aside, leaving him feel betrayed.

“This company is still lying to people who are new to Uber to get them joining it,” he said. “These new drivers are still dreaming. They think today they start driving, tomorrow they can buy a house. I am awake from the dream now. That’s why I quit without doubt.”

According to previous public statements, Uber has pledged legal assistance to drivers in trouble. It has also signed a deal to secure third-party insurance with AIG, minimizing drivers’ liability on that front.

The company, however, declined to address specific questions about its legal support for prosecuted drivers or exactly how it justified putting people working under its brand in a position where they’re breaking the law.

Instead, in a statement emailed to Coconuts, Uber said it had been “humbled by the enthusiastic response” to ridesharing in Hong Kong and pledged cooperation with authorities.

“Everyday, thousands of people use the Uber app to get across the city or to access flexible economic opportunities,” it reads.

“Uber is committed to working with the government and other transport operators on ways to regulate ridesharing, and has been encouraged by the government’s endorsement of sharing economy reform.”

Future

Despite operating under a legal cloud, and even once being raided by authorities, Uber publicly remains optimistic about its prospects in Hong Kong.

But drivers aren’t so sure.

Some, like Prius, don’t even particularly want ridesharing legalized, noting the potential influx of competition for himself if it gets an official green light.

“I would rather the government just ignore it, just let it be,” he says.

Frankie, a cigarette trader who started taking passengers via Uber a month ago for some side cash, thinks it’s unlikely the government will change its mind.

On one hand, he argues, they fail to recognize that drivers like him serve a different demand than conventional cabbies, particularly for tech-savvy youth and non-Chinese speaking customers.

“Why do they call Uber? Because they speak English, and it’s easy to put in the destination, especially for the traveler or visitor — it’s easy for them to manage… they don’t have to argue with the driver,” he says.

But even then, he believes the taxi industry’s political influence will remain a barrier, though he’s unconvinced the current case against drivers will succeed, arguing that because the transaction goes through Uber, and money doesn’t pass immediately between the driver and passenger, there’s insufficient evidence for a conviction.

“For me, I don’t think it’s easy to [be found] guilty; it’s difficult to prove it,” he says.

Nevertheless he says he’s not a big fan of Uber as a company — calling their cut unfair — and says he’s even emailed the company’s US rival Lyft to try and induce them to enter the Hong Kong market.

Stephen also feels Uber “takes us drivers for granted.” Though he appreciates the platform, he feels the company’s future in Hong Kong is tenuous at best.

“Our Hong Kong government is not so smart. They won’t come up with practical ways to tackle this problem,” he says.

“They like the situation to stay as it is now, or wait for the market itself to figure it out. If one day the courts have a solid decision that Uber is illegal and should be banned completely, then Uber will disappear in Hong Kong.”