After graduating abroad from university with an English degree in 2017, I had little trouble finding an English-teaching job back in Hong Kong.

At the first tutorial center I worked at, I met Illiana. Her English was impeccable, and she spoke fluent Cantonese, Spanish, and her native tongues of Cebuano and Tagalog. I found Illiana’s work ethic truly inspirational and she radiated such enthusiasm. Her students genuinely loved her.

By day, she was an English teacher. By night, she was a Masters of Education student. Her time in the university classroom proved to be more about self-improvement than adding another qualification to her already impressive name.

Illiana ticked all the boxes— just for my ex-boss to reassure skeptical Hong Kong parents that she was not a domestic helper working illegally. At times, prospective parents left unconvinced and turned to our neighboring competitors.

Our co-workers on the other hand, all white twenty-somethings from the US, UK, Australia, and New Zealand, were zealously accepted by local parents. Their qualifications and work experience were never once brought into question. And if you ask them how they landed their positions, some will say nonchalantly that they “fell into teaching.”

Illiana’s story is but one of the many examples of the racism that plagues Hong Kong’s education industry — everyone plays a part, including employers, parents and the “teachers” for whom Hong Kong is just another stop on their Asia bucket list.

Conflating whiteness with competence

I speak from a place of privilege. I was born in Singapore, moved to Hong Kong soon after, and attended a through-train international school for Singaporeans. With an ethnic Chinese last name and an English degree from an Australian university, parents or employers rarely interrogate me about my qualifications and abilities.

In my five years as an English teacher, it’s clear that Hong Kong is a very attractive place for foreigners looking to tutor English. Why earn a modest income in a developing country when you can live comfortably in Hong Kong, jet to Hanoi or Bangkok for a weekend and come back to a cushy teaching job that could pay upwards of $25,000 (US$3,205) as a monthly starting salary?

And because there is no shortage of English tutoring jobs in Hong Kong, even less-than-qualified teachers are welcome. Hundreds of branches of franchised tutorial centers, run more like businesses chasing a quick turnover, are happy to offer full visa sponsorship to a white face. Far too often, being native in a language is automatically assumed—incorrectly—to mean expertise in teaching it.

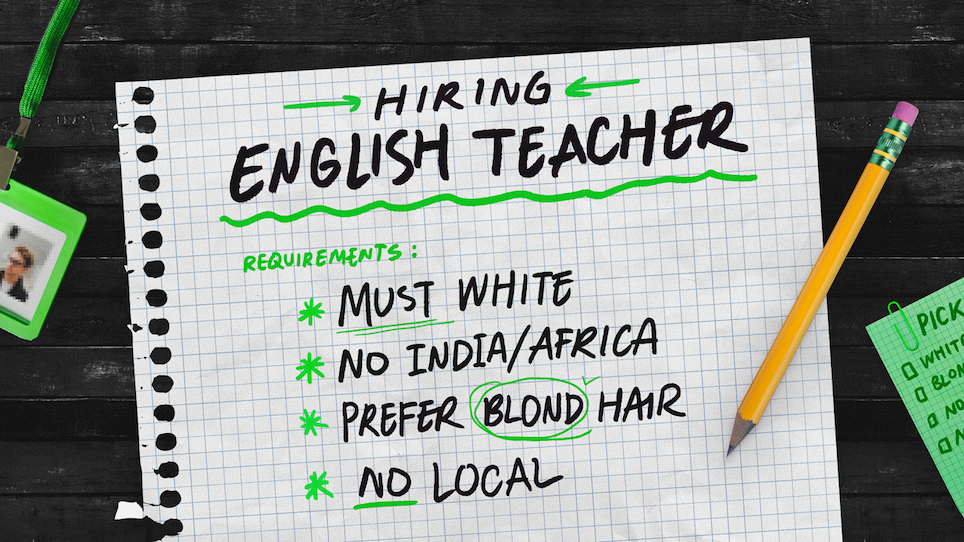

Last year, a photo circulated on Facebook appearing to list hiring requirements from a number of employers, presumably schools or tutorial centers. The list blatantly declared preferences for physical appearance such as “blond hair” and “must white,” while one employer specified “No India/Africa.”

Many were shocked at the photo, surprised that such unabashed racism could be endorsed in an industry educating the future generation. But for those of us who are teachers, we know this discrimination unsettlingly well.

I’ve witnessed my ex-boss at my previous tutorial center throw out resumes submitted by people with Filipino, South Asian or vaguely Muslim-sounding last names. Sure, like in any recruitment process, there were candidates who were sorely unfit for the job. But many had impressive achievements.

“Audrey, how do you pronounce ‘O-U-S-M-A-N-E’? Meh dei fong lei ga (咩地方嚟㗎),” she once called out to me, just to chuck the résumé in the bin before I could respond.

‘Just a casual thing’

The students also get the short end of the stick when they’re taught by people who come and go as they please, who regard teaching as just another way to make money to fund the next stop.

“That’s just the way the industry is,” an English teacher once told me when I challenged his motives for teaching in Hong Kong. On social media, he is a self-described backpacker, travel writer and social media expert. Teaching, he said, “is just a casual thing.”

I came to resent people like him. Hopping from one far-flung classroom to another, they do no favors to the children who would benefit much more from an educator who could build a relationship with them and tailor their lessons according to their progress over the years.

Psychologically, it is also harmful for young, impressionable children to grow attached to a mentor—only for them to leave months later.

Schools and learning centers in Hong Kong need to play a crucial role in de-colonizing the mindset that only white people can teach English well. Ethnic minorities who were born and raised in Hong Kong, and have the advantage of knowing Cantonese, are far better suited to teach struggling second-language learners than foreigners “finding themselves” in Asia.

It might not be good for business—after all, many parents want their children to learn from Caucasians over locals and ethnic minorities. But more thoughtful and stringent hiring practices would go a long way in ensuring that students are taught by more competent and passionate teachers who are focusing on their job at hand.