Like the antique shops on Hollywood Road, or the Man Mo Temple near his stall, Tin Yim-keng harks back to an earlier time in Sheung Wan, before the hipsters, trendy cafes, and avocado toast.

The 92-year-old — known as Uncle Tin — has long been a familiar sight on the steps of Ladder Street where, every January, he sets up his fold-up table and practices the ancient art of calligraphy, surrounded by reams of red paper, ink brushes, and tins of gold paint.

The nonagenarian creates and sells banners called “fai chun,” decorations with hand-painted greetings for Chinese New Year.

The adornments are typically hung on a home’s front door and convey phrases wishing people good luck, and prosperity for the year ahead.

In a city where old traditions are routinely eschewed for the new, and where few have a moment to stand still, Tin takes his time, carefully tracing each character, preserving with paint what he calls “the essence of Chinese culture.”

‘What would you like me to write for you?’

On any normal day, Tin looks like any other elderly Hongkonger, his slight and unassuming appearance belying his skills with a calligraphy brush.

On a recent morning, he wore an English football jacket, which made his frail, barely five-foot frame appear even smaller. Wisps of his grey hair peaked out from a baseball cap atop a friendly face with sunken cheeks.

As Coconuts approached, Tin offered a fai chun on the spot. The offer accepted, he pulled out two reams of red paper and folded them in half, twice.

“What would you like me to write for you?” he asked.

A steady stream of curious passersby, ambling though the Upper Lascar Row antiques market nearby, slowed down to take photos as Tin began work on a banner wishing good heath for the new year.

With a confident and steady hand, he dipped his brush into the pot of gold paint and, stroke by stroke, wrote the phrases “wishing you good health” and “may you be as energetic as a dragon and a horse.”

Back in the days

Tin, a licensed optometrist, has been practicing Chinese calligraphy for more than 70 years.

“I taught myself calligraphy,” he explained, as we spoke at this stall.

“When I went to school, at that time, everyone learned how to write with ink brushes. When I was a kid, I followed my godfather, who was a doctor, and he would write out everything using ink and brush. So I would copy the way he held his brush and the way he wrote.”

Clearly, gone are the days where prescriptions are written with an ink brush, and thus the rarity of seeing Tin’s tradition method intrigues onlookers.

“When I was kid, everyone learned how to do Chinese calligraphy, and even kids wrote their own fai chun. These days, no one learns,” remarked one woman passing the stall.

Tin eagerly chimed in: “Of course, not a lot of people know how to do calligraphy. You can see a lot of people these days don’t even need to hold a pen for work! They just use computers to write things.”

The craft is far from straight forward.

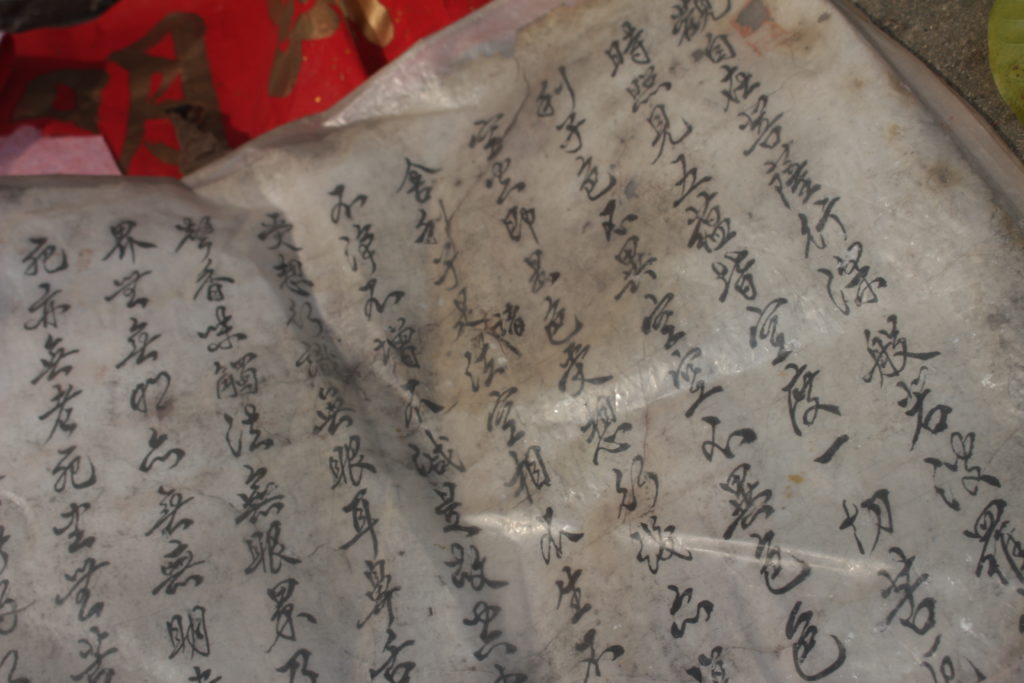

Even after the better part of a century, Tin admits he still makes mistakes, something he’s more than happy to demonstrate by running to a nearby metal hut (where he keeps the glasses he sells) to retrieve an example.

The aging paper (above) bears his own handwriting.

“Look!” he laughed, pointing at a line on the now damp and moldy scroll, “I missed out a character. Even people who know calligraphy make mistakes!”

They come from far and wide

The value in hand-painted fai chun comes from the small differences in each one.

Tin’s banners are carefully written on paper with messy edges — he cuts the long reams using a knife instead of scissors. The delicate flecks of gold paint look ready to peel. The stray ends of the calligraphy brush show in each stroke.

“Each one is unique” said Tin, as he pulled out what at first appeared to be two identical fai chun with the same couplets to point out the subtle differences in both.

Tin sells small banners for HK$80 (just over US$10) and asks HK$300 (US$38) for larger ones that go from ceiling to floor.

The prices may seem steep for what are temporary decorations, especially considering that stationary shops nearby Tim’s stand sell packs of mass-produced fai chun for as little HK$6 (about US$0.77).

His efforts, nevertheless, remain popular, with market vendors, tourists, and even people from Beijing with businesses in Hong Kong stopping by to buy a set.

“I have a few regulars, but not a lot of young people buy them, it’s mainly people from the older generation who buy fai chun that are written by hand,” he said.

Soon approaching his 93rd birthday, Tin said he has no plans to stop yet. In fact, another thing belied by Tin’s slight appearance, is his passion for hiking.

“I’ve been with this hiking group for about 40 years. Hong Kong Island or Kowloon, whatever hiking trail there is, I have done it: Tai Mo Shan, Ma On Shan, Pat Sin Leng, and so on,” he said.

“I can still walk and run, so I’ll keep on doing this.”

Though he’s watched as traditional calligraphy disappears, Tin conceded he hasn’t really considered teaching classes to pass on his skills. He did, however, have some advice for people who want to learn.

“Calligraphy is hard, but it’s not too difficult; there’s just a lot of characters to learn,” he said.

“When calligraphy masters do this kind of work, what they are really doing is protecting the essence of Chinese culture,” he said. “It’s holding on to a traditional way of writing, and that’s what I’m doing.”