Mario de los Reyes is gasping for air.

It’s just after midday on a hot afternoon in late May and the sun is baking the concrete yard where the 64-year-old has been playing football with fellow maximum security inmates at Stanley Prison. But this isn’t just the heat and exertion from exercise; something is wrong.

This fatigue is abrupt, like a switch has been flipped and his energy zapped immediately. His face flushed, he staggers to the side of the field and slumps to the ground. Soon, medical staff appear at his side. In this, his 24th year in prison, Mario is having a heart attack.

A quarter of a century ago, Mario was involved in a violent altercation in Sai Kung. A man was fatally stabbed. While the attacker who wielded the knife was never caught, Mario and another man were convicted on a joint-enterprise charge of murder. He is now among 264 inmates in Hong Kong serving an indeterminate life sentence, meaning there is no set date for release.

After 10 rejections, and following the health scare in May, he’s holding out hope of release next year. But, with the review board characterized as harsh by critics, uncertainty prevails.

While life in prison implies a definite, albeit long, jail term in some countries, those serving indeterminate sentences in Hong Kong have no fixed date of release. Their fate, instead, rests in the hands of the Long-term Prison Sentence Review Board, which makes recommendations to the city’s leader.

The board’s decision-making process has been criticized as opaque and harsh by prisoners’ rights advocates, with inmates often legally unrepresented and rarely given the chance to present their case in person.

Outcomes, usually, are negative. Of 221 indeterminate sentences reviewed in the past two years, 21 were recommended for conversion to a finite term. The board also advises on sentence reductions for terms of longer than 10 years. It’s reviewed 510 in the past two years. It’s reduced six.

Whether the results produced by the system are fair, of course, is a matter of perspective on the roles of deterrence and rehabilitation, punishment and redemption. In Mario’s case, supporters point to his record of good behavior, his completion of numerous educational courses, the assistance he lends to other prisoners, among reasons his release is warranted. In their rejection last year, the board simply stated upon assessing his case he’d served an “insufficient” period of time.

Absent the reasons underpinning the review board’s decisions, the only choice is to wait and lodge another application, which can be filed, first, after five years in prison, and then every two thereafter.

“There’s no use reasoning,” he said recently, speaking through a phone behind the glass that separates visitors from inmates in the visitor wing. “I do not expect anything now, whatever comes I have to accept it. I have to accept if I cannot get out.”

A DEATH IN SAI KUNG

Mario is sprinting back to a taxi.

It’s just after 7pm on Feb. 18, 1993, and dark on the Sai Kung street where, nearby, Eduardo Vera Cruz, is slumped, clutching his side. As Mario and four others flee toward the cab, Eduardo is dying. The 35-year-old squats as his wife presses towels to his torso, trying to stem the blood spilling from two stab wounds inflicted by the blade of 18-centimeter long folding knife. His punctured heart will not last much longer. Soon, the knife will become a murder weapon, a murder weapon that belongs to Mario.

A year later, knowledge that this knife was in the possession of his friend named Marlon will form an important part of the case against Mario and his co-defendant, Orlando Pagatpatan. Marlon, there’s no dispute, is the man who delivered the fatal blows. But in the weeks after the killing, he manages to flee to the Philippines, leaving Mario, Orlando, and two others involved to face the police.

The others are Naty Palenia and her 21-year-old son Reynaldo, also known as Jun Jun, who worked with the victim at a garage in Sai Kung. Without them, it’s fair to say, there would have been no murder. During a trial, the court hears how Naty, upon hearing her son was called a drug addict by Cruz, arranged for Mario, Marlon and Orlando to accompany her to confront him.

In Mario’s telling, he was sought out by Naty — whom he called an acquaintance — to find her “runaway” son because, as a driver and tour guide, he had access to a car, and was familiar with Sai Kung. He said he had no knowledge of any dispute and was surprised when, “at the last minute,” the two other men joined the trip.

“She showed me the address and asked if I happen to know the place where she suspected her son of working and I said to her that it’s on the way where I often bring tourists, where those seafood restaurants are concentrated along the coast,” he wrote in a letter to Coconuts HK.

“She even suggested that if that is the case, then we will go and eat there after we located and brought back her son with us.”

But prosecutors — who did not pursue charges against Naty — presented a different narrative, characterizing the three men as “back-up” brought in the event things got violent. According to court documents, after a brief argument, Orlando was the first to strike the victim, who was also punched and kicked. During the trial, Mario maintained he did not take part in the attack but, in a letter to Coconuts HK, acknowledged that he kicked Cruz, something he claimed was a “reaction” because he believed him to be going for Naty. He claimed he then tried to help Cruz up.

Under a joint-enterprise murder or manslaughter charge, two or more people engaged in a crime together — even if they didn’t plan to kill — can be culpable for the actions of accomplices, if the outcome was something that, reasonably, could have been foreseen.

In 2016, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom, in the landmark decision of Jogee, reversed previous case law on joint enterprise, which itself had been based largely on a Hong Kong court decision from 1985. They ruled it was wrong to treat “foresight” as a sufficient test to convict someone of murder. Hong Kong’s Final Court of Appeal, however, ruled the UK decision should not be adopted in the city.

NO HOPE

Earlier this year, university researcher Tobias Brandner, Hong Kong radio host Bruce Aitken, and prison chaplain Father Pat Colgan founded Voice of Prisoners, an NGO to lobby for prisoners rights.

Among their aims, the group wants to see limits on phone calls and visitations eased, “heavy” sentences, particularly for drug mules, reviewed, and the “black box” of the Long-Term Sentence Review Board opened up. A former inmate himself, having served time in the US for a money-laundering conviction, Aitken knows first hand the weight of incarceration. His frustration with what he calls the “cruel and inhumane” situation of indeterminate sentences shows.

“They should at least give someone a release date,” said Aitken, host of “An Hour of Love,” a radio show that caters to prisoners. “The thing about the board is they don’t give anyone hope.”

Brandner, an associate professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who has studied the city’s prison system for two decades, suggests that inmates, after 15 years, should automatically get a duty lawyer to handle their reviews. After 20 years, prisoners should appear in person before the panel. “The tough thing is that inmates do not know what happens in this small board, it’s totally vague,” he said, calling sentences in the city “too long in general.”

Aitken, however, knows they face a tough battle. “How do we move this elephant?” he said. “There’s not a lot of public sympathy.”

GUILTY

Mario is being judged.

It’s mid-afternoon, Feb. 24, 1994, and the jury has returned. The foreman has announced a unanimous verdict of guilty. He stands with Orlando in the defendant’s dock at the High Court while their personal details are read for the record. Mario, the court hears, was born Jan. 19, 1951, in the Philippines and graduated from Wesleyan University. He was a soldier before coming to Hong Kong in 1989 to work. His family, a wife and three, children remained behind.

The court doesn’t hear the rest; it’s not suppose to. It doesn’t hear about growing up working class in the northern city of Laoag, the eldest of four siblings, the big brother. There’s no mention about rising early to hawk newspapers and shine shoes; about weekends as a pinboy at the bowling alley; about winning a scholarship for disadvantaged students to attend high school; about the nights pedaling a three-wheel pedicab to pay for college; about playing national-level table tennis; joining the military; fighting Muslim secessionists in the south; about meeting his wife.

It doesn’t hear what it was like to first visit Hong Kong in the autumn of 1987, to feel the balmy October weather; see the crowded concrete jungle, everyone in a hurry, pagers and beepers on their belts, the neon lights flooding the buildings at night. It’s about 3pm when Justice Stuart Moore tells Mario and his co-defendant to sit.

A year later, Moore will write a letter to the governor in support of future sentence reviews for the pair acknowledging the outcome “might have easily gone either way” — that a “more merciful jury” may have recorded a verdict of manslaughter.

But on this, the day of sentencing, he is stern. He condemns the “cowardly attack” on someone that “stood no chance”, a victim, he says, who was killed carelessly and brutally for almost no discernable motive.

“The only sentence that I can pass for murder is one of life imprisonment. And that is the sentence on you both. You both go down.”

MY WORLD

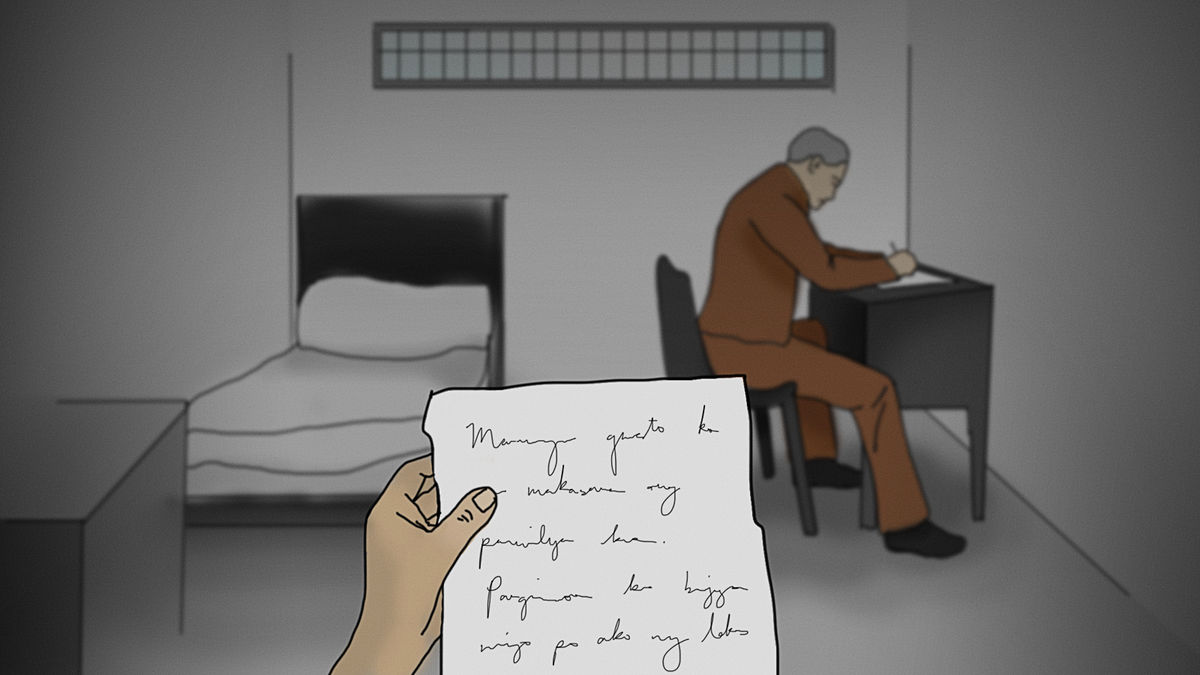

Mario is writing in his cell.

It’s 11pm, Sept. 17, time for lights out — or it should be. The guard, a good friend, allows Mario to continue filling the A4 loose sheets with his careful cursive handwriting. Letters, a rarity in the digital age, are important for a man who’s never been online, an escape from the regimented life of a prisoner.

The tedium and boredom suppresses emotions in inmates; tempers flare but guards move quickly, he writes. Between one hour of exercise and meals, prisoners work in the workshops making uniforms for the Correction Services Department, only God knows how many stitches he’s sewn in a quarter of a century. He used to sew buttons, a job with ample downtime, but switched after the heart attack to a unit that makes trousers. Less time for writing now, he laments.

He writes for himself and others, to newspapers, other inmates, politicians, old friends and, recently, Coconuts HK. He writes stories and essays for the prison’s magazine, Rainbow. He helps inmates enrolled in courses with assignments, assists the newly incarcerated draft letters of appeal. Many female prisoners write to seek his opinion on how to adjust to prison, or just to tell their stories.

“My co-inmates are already used to seeing me always writing and they sometimes told me that I am creating my own world; which is true,” he writes.

“All these things helped me to forget and pass the time and years and I can’t believe that I have already served a quarter of a century behind bars. Time flies so fast in my life without knowing it.”

To this day, Mario maintains he is innocent of the crime of murder. He blames Naty and Marlon, who he said was a friend and, at the time, a new member of a group he and some Filipino expatriates founded called Utol, a colloquial term for “Brother” in Tagalog.

He says the reason Cruz was killed an “enigma” though speculated Marlon was trying to impress Naty, with whom he was in a relationship. Imagining life for the victim’s family, robbed of their father, husband and main breadwinner, his eyes swell with tears, Mario writes.

“I am so sad and full of pity for the victim. I can just imagine how his wife and children grieved and suffered,” he wrote in one of his letters, during which he repeatedly reiterated he was not aware of any plans to confront anyone on the day of the murder.

“I swear to God that I am innocent of this crime, but the law thinks without doubt, or beyond reasonable doubt, in the contrary.

“I felt so aggrieved that I was unfairly convicted of a crime I did not commit but, as I have said, I have to respect the rule of law, for I cannot do anything more.”

After his arrest, Mario’s wife, Gigi, moved to Hong Kong to work as a domestic helper. For 16 years she visited prison every Sunday but, last year, upon the advice of their children, returned to the Philippines, where she now waits for his release.

In a recent phone interview, she recalled meeting her husband as a young soldier stationed nearby her home. They married in 1975. The first her children learned their father was in prison, she recalled, was when Mario was interviewed for a news report prior to the 1997 handover.

Next year, Mario is eligible for a special review, a more in-depth assessment of his application for a release date. Gigi says she has sacrificed much but never given up hope.

“I want my husband to come home,” she says.