In recent months, old-school Hong Kong comics appear to be gaining much attention. Alfonso Wong – the genius behind the Old Master Q series that has captivated countless readers since 1962- showcased 128 drawings at Sotheby’s this month. All those pieces were sold at the event, which drew more than 5,000 visitors in 10 days, evidence that fans are still rabid for traditional comics.

And coming this November, expect an exhibition by another homegrown comic mastermind, Theresa Lee Wai-Chun, the artist-author behind the popular Miss 13 Dot series. Her “13-Dot” exhibition at Comix Home Base in Wan Chai is also hotly tipped.

To the undiscerning observer, it’s easy to interpret these signs as evidence of a healthy homegrown industry. In truth, however, they are rare moments of reprieve from a harsher reality: the traditional comic industry in Hong Kong is dying. Its pains have frequently been reported in the media – years of declining book sales; industry players struggling to make a living. What led to this predicament? Does the highly visual book culture, which has captivated many generations of fans, have a future or will it one day become a relic, only accessible at cultural exhibitions and auction houses?

Theresa Wai Chun Lee’s Miss 13 Dot comics

During the heydays for comics in the 1980s to 1990s, illustrators like Hong Kong artist Elphonso Cheung-Kwan Lam could make a living drawing comics exclusively, just as he did while working on titles like ‘True Love’, ‘The Jam’ and ‘Super Seven’. “Now, if I only write comics, I wouldn’t make enough income,” he tells Coconuts HK.

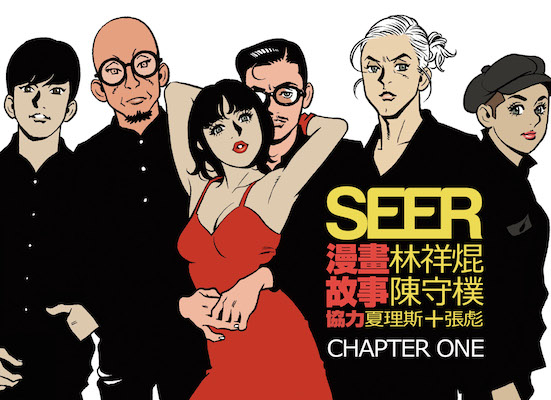

Lam’s latest comics include ‘Seer’, which is featured in Good Life magazine, and the artist also just released ‘The Greatest Hits’ this month, a collection of short story illustrations he penned from the 1990s to now. Additionally, he juggles many jobs to supplement his income, including storyboarding for films, design work for fashion brands, figurine production and more. The 43-year old says many industry veterans like himself have seen their profession dwindle into side-jobs.

The main culprit behind this predicament? “Free website comics have destroyed the industry,” he says. Readers can get shorter four-block strips online, which are updated frequently, at no cost. Like many industries disrupted by the internet revolution – music, newspapers, TV and films – the comics scene is struggling against the tide of free original or pirated content. “In this age, readers think they don’t need to pay for comics, like free music,” says Lam.

The threshold to enter the scene has become low; anyone can become a comic artist, all you need is a website. Traditionally artists like Lam laboured for years to acquire skills to draw comics and to secure opportunities in the profession. Success back then meant generating quality books that achieved high sales. Now? “If you upload comics in a website and generate many clicks, you can become famous,” says Lam. He thinks poor quality digital content by amateurs has contributed to the industry’s collapse.

Official statistics about this sector are difficult to come by, however, Alan Wan, CEO of Anitime Animation Studio and a director at the Hong Kong Comics and Animation Federation, reveals educated estimates. He was in the business since 1990s to 2010 in various capacities (from content production to licensing and management), and recalls the peak time between 1995 to 2000 when the market generated around HKD700 million from local comics, Chinese-translated Japanese Manga and more. “By 2010 that figure fell to around HKD300 million, a drop of more than 50 percent,” Wan says.

Elphonso Lam’s The Greatest Hits

These numbers were collated from more than 80 companies that were part of the Hong Kong Comics and Animation Federation. The executive agrees that free digital comics have obliterated a significant portion of the market, but stresses that a toxic storm of other factors has also contributed to the current pains. There’s the dwindling distribution network. For instance, comic bookstores are a dying breed. There were around 350 comic stores at the peak of the market, now there are less than 100, he says. Likewise, street news vendors (who comic publishers depended on to stock their print material) are nearing extinction.

“The Hong Kong government will not grant new licenses to newsstands, which is why you see them less nowadays.” Additionally, these independent street operators are unable to compete with the proliferation of convenience store chains, which have become a more prevalent medium for selling various printed material. “ 7/11 and Circle K charge higher fees than newsstands to have their content stocked in their stores, so many comic book publishers do not use this new platform.”

Elphonso Lam’s Seer

The industry veteran left the local comic scene four years ago to join the animation TV, film and toy business in mainland China at Anitime Animation Studio. “It’s tough being in a new business and a totally different environment, but if I stayed in Hong Kong I would have faced shrinking my business and changing everything just for a small market.” Wan would rather work hard to overcome his challenges in China (which includes different rules and audience tastes), as he’s optimistic about the prospect of greater gains in a bigger market if he succeeds.

Many former publishers like himself have adapted in the new era he says, whether it’s switching to different markets or mediums or branching out to other sides of the business such as licensing content to gaming companies. “You can’t just rely on the old market of comic book publishing.”

Yet he remains positive about the industry’s outlook, hoping it becomes more creative and innovative amid the evolving times. “People want more content from many devices, not only from publishing but from TV, mobiles, games and websites.” Wan insists than in these more connected and globalized times, content producers need to revaluate their competitors and consumers, as every product needs to be international, not local. “Your competition is now worldwide,” he says. So locally-focused content such as political comics, which only Hong Kongers can appreciate, won’t export well under Wan’s framework. He advises instead: conceive good content that attracts a broader audience.

Theresa Wai Chun Lee’s Miss 13 Dot comics

Lam agrees that a greater diversity of comic styles is needed as the new generation of readers demand new stories and visuals. While other leading comic nations like the US and Japan have worked to stay in tune with the evolving readership, this is not so in Hong Kong. “Many old-school comic artists have not updated their kung fu-style, which was popular in the 1960s to 1990s,” explains Lam. The artist adds most young people find these fighting comics outdated. “Now they want lifestyle comics about girlfriends and boyfriends, families or themes relatable to the troubles in their lives.”

He’s pessimistic about the industry’s future, citing the demolition of the Kowloon Walled City as an example of how culture and history is unappreciated in Hong Kong. “People’s style here is money, money, money. They don’t want to keep the culture. They just destroy and destroy.”

Asked whether he foresees breakthroughs in the industry anytime soon, he simply shrugs and answers: “No chance.”