Dawn turned 30 in April. Her birthday celebration, like for many in pandemic-hit Hong Kong, was low-key this year—just a video game marathon and a gathering at home with friends and family.

As she leaned over the candles of a store-bought cake, her wish for her turn of the decade was simple: The devout Christian prayed for birth certificates for her and her 29-year-old sister, Kaye. They had been waiting for them anxiously since applying in Oct. 2019.

The two siblings were born in Hong Kong, their mother, Feli, a former domestic worker from the Philippines who overstayed her visa in the late 1980s. She gave birth to them at Queen Elizabeth Hospital after terminating her contract with her employer. (For privacy reasons, the family declined to have their last names published.)

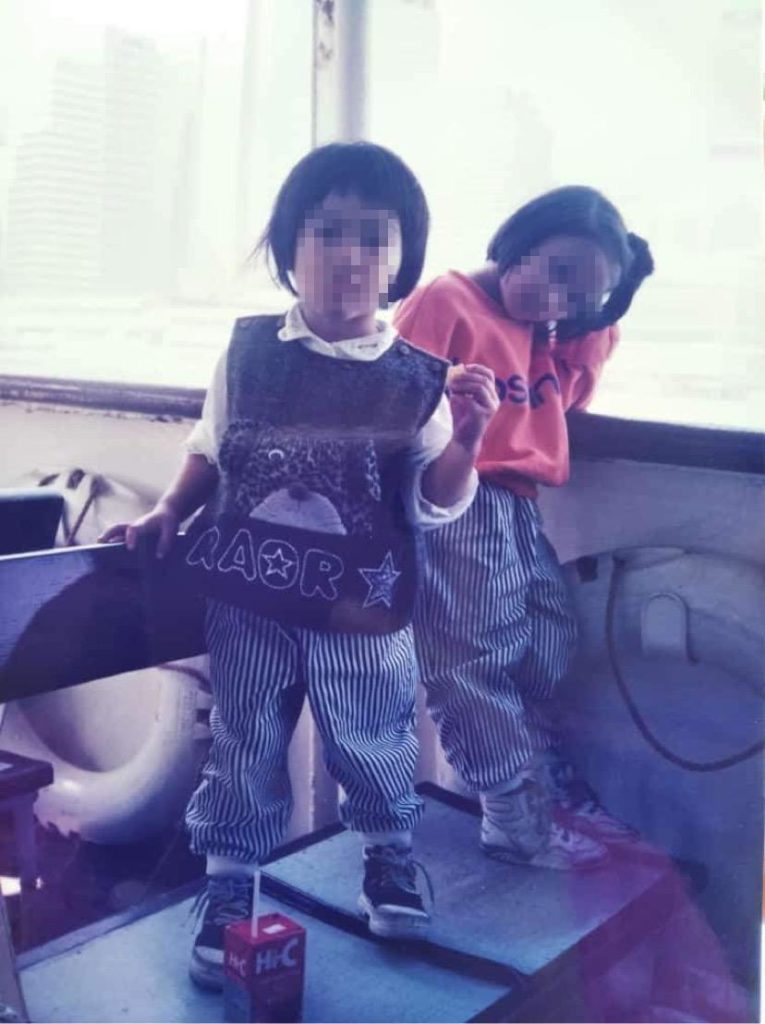

Afraid of being detained, arrested or having her daughters taken away, Feli did not register their births. Without any documentation, her children never went to school or set foot in a hospital. Their biological father and Feli’s then-boyfriend, a Filipino musician, left them two years after Kaye was born.

In an interview with Coconuts on a November afternoon, the sisters’ confident, articulate speech belied their lack of a traditional education—a testament to their mother’s dedication in homeschooling them herself, and all the books they borrowed with a friend’s library card growing up.

Dawn said they’ve moved at least 15 times in the last 30 years, bouncing from the home of one church friend to another. In return, the sisters and their mother helped their friends with cooking, cleaning and other chores.

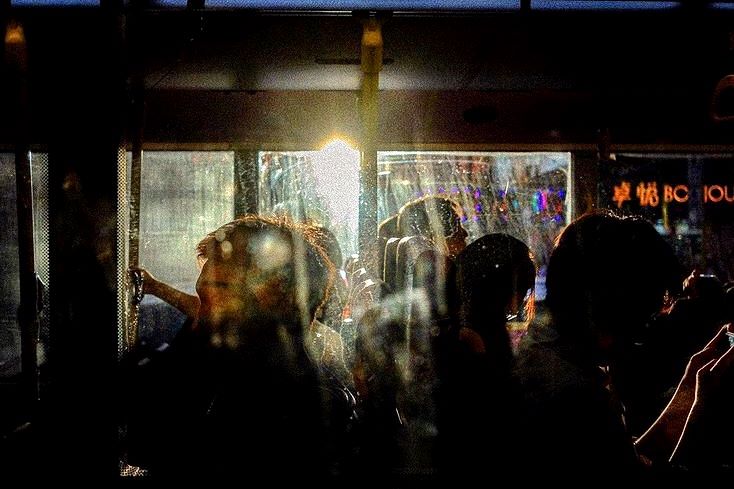

It wasn’t until last October that the family sought help, a decision prompted by the anti-extradition protests that saw police conducting random ID checks on the streets. Their biggest fear, the two sisters said, was being stopped and searched.

“We don’t look like we’re 30, we look like we’re 16, or 25. Those were the targets that [police] checked. It was terrifying for us to go out,” Dawn said.

They decided to reach out to PathFinders, a Hong Kong-based NGO that supports migrant mothers and their families. PathFinders met with the mother and two sisters, arranged for them to take DNA tests to prove their blood relations, and hired pro bono lawyers to assist their case.

On Oct. 16, 2019, they surrendered at the Immigration Department’s general investigation section in Kowloon Bay. Staff shot each other incredulous glances as the siblings explained they had been living under the radar for three decades.

“Some of the officers were asking us off the record, ‘How did you survive? [How] did you learn? Do you know how to speak?'” Kaye said.

After lengthy interviews with the officers, an emotional eight hours in the immigration building ended with the family obtaining recognizance papers, a document that does not afford them any rights in Hong Kong but serves as proof of identity. They escaped detention and were released on bail of HK$100 (US$13) each. They had to report back to the department every four weeks.

“I was so scared and I didn’t know what to do,” Feli said, recalling how she felt as immigration officers questioned them. “I prayed, ‘Lord, I know this is your time.'”

A milestone

Dawn got her birthday wish—albeit belated—two months ago. Their birth registration, a typically straightforward process, was made arduous by a lack of supporting documents and the sheer fact that their registrations were 29 and 30 years late.

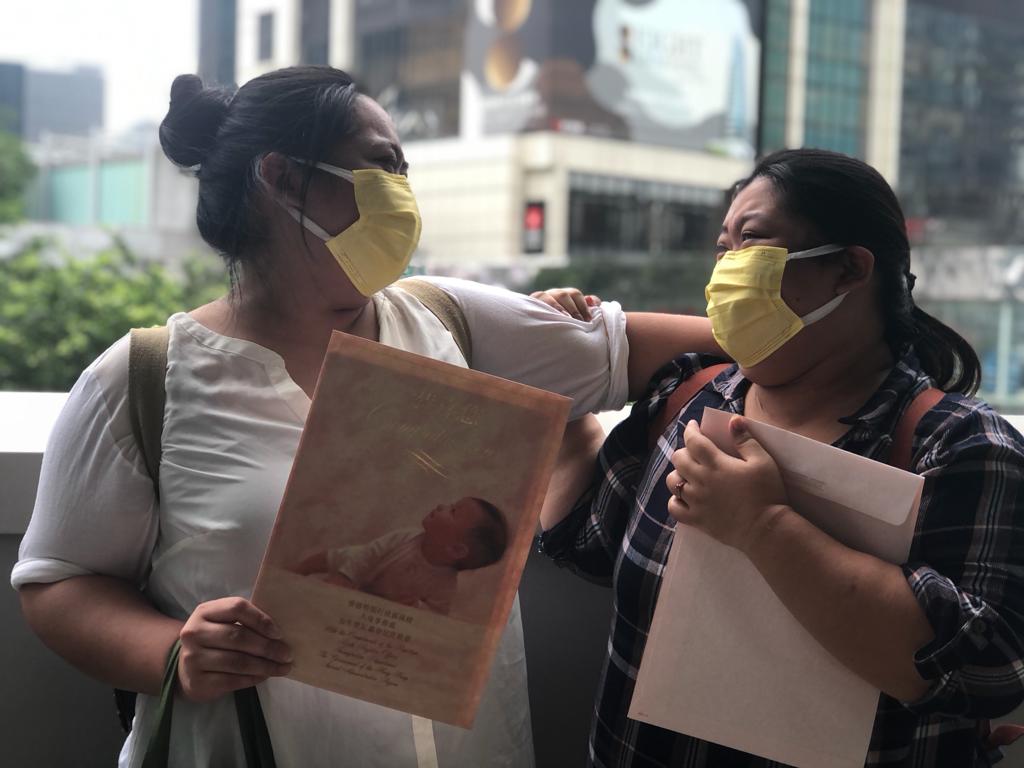

On Oct. 22, she and her sister finally received their birth certificates—seen later by Coconuts—from the birth registry office in Admiralty, marking a milestone in their journey to freedom.

“That moment was so priceless,” Hina Ali, a PathFinders caseworker assisting Dawn and Kaye, said. “What they’ve been through is very personal and difficult. We’ve all been very lucky and fortunate that it could have such an ending because anything could have happened.”

Now, Dawn, Kaye and their mother Feli are counting down their days in Hong Kong. With birth certificates in hand, the two sisters, together with their mother, went to the Philippine consulate on Nov. 26, where they received temporary travel documents to fly to the Philippines.

The consulate confirmed with Coconuts that they had issued the papers to the family members, and that the three were assisted by the Immigration Department.

The sisters hope to fly out before Christmas, which they want to spend with their grandmother—who they only know through shaky video calls—in the northern part of Luzon, the island where capital Manila is.

The Immigration Department told Coconuts it will not comment on individual cases due to privacy concerns.

Hong Kong’s longest known delay in birth registration

Dawn and Kaye’s stories are, by a wide stretch, the longest cases on record of an individual living without an identity in Hong Kong. In 2015, an undocumented 19-year-old male born to an Indonesian mother, formerly a domestic worker in the city, became the longest known birth registration delay. (His two siblings, aged 17 and 18, also had no identity documents.)

Earlier on that same year, news of an undocumented 15-year-old girl jumping to her death from a luxury Repulse Bay apartment made local headlines. Her parents, a well-to-do British insurance broker and a former domestic worker from the Philippines, sent her and her younger sister to a private tutorial center.

The suicide shocked Dawn, who said she spent hours reading news articles about the tragedy.

“It’s such a heavy thing in my heart. I know how she felt, to be different, to have a lot of limitations. If I knew her, I would most likely reach out to her and let her know she’s not alone,” she said.

It was in one news article Dawn read, which quoted a PathFinders officer, that she realized there was help available for people like her. But when she talked to her family about turning themselves in, her mother recalled what one law firm she approached 10 years ago had warned: Their case was too difficult, and they couldn’t rule out worst-case scenarios—like incarceration—if they were to come forward.

Discouraged, the family continued their lives underground.

Following the teenager’s suicide, the Immigration Department found 151 cases between Jan. 1, 1990 and May. 26, 2015, in which a baby’s birth remained unregistered for more than 12 months after.

The department told Coconuts it does not have an updated figure. In an email, the department noted parents in the city must register the birth of their Hong Kong-born child within 42 days of delivery, or face a maximum penalty of HK$2,000 (US$260) or up to six months’ imprisonment.

Bittersweet farewells

For 30 years, the family called Hong Kong home—but the city whose shadows they lived in scarcely knew of their existence. Before they surrendered, the sisters and their mother wondered if they would forever be in a state of limbo.

“I’m excited to start a new life but at the same time, it’s bittersweet,” Dawn said. “It will be such a huge change. I’m praying I will be fine.”

Kaye, the softer spoken of the siblings, already expects she might grow homesick for Hong Kong. But she has adventures to look forward to: In the Philippines, the photography enthusiast plans to enroll in art school. The 29-year-old is used to snapping Hong Kong’s busy, narrow streets, which she captures on an old camera a friend gave her. Her new home will be a whole other landscape.

They’ll leave behind their friends, many of whom opened up their apartments for them to live in. Dawn and Kaye have attended the same church since they were in their early teens, when they were active members of their youth group and regularly performed with their church friends.

The family’s departure date is still unconfirmed. They are waiting on the Immigration Department to respond to their request for air tickets to the Philippines, PathFinders said.

For Feli, who is pushing 60 and just learned in her first medical check-up in decades that she has high blood pressure and diabetes, a slower and less anxiety-ridden life in her home country will be a welcome change of pace.

“Hong Kong is so amazing. There are a lot of things you can do here. If I am not an overstay[er], I would have done a lot of things in Hong Kong. It’s so sad [we] cannot because of our situation,” she said.

Speaking for her daughters too, Feli added: “We’re going to miss Hong Kong.”

PathFinders provides access to free humanitarian and legal services, enabling Migrant Domestic Workers (MDWs) with children to make informed decisions. You can reach out at +852 5190 4886.