G. has no recollection of when she was photographed.

Judging by the sleeveless dress she’s wearing and the fact that she doesn’t have a mask on, sometime last summer is her best guess. The picture was taken in Central, where she works at a finance company. In it, she’s speaking mid-sentence with her colleague, her mouth slightly open.

A year later, the 27-year-old’s photo has wound up on an Instagram page, @streetstylehk. It’s one of almost 400 other photos on the account’s colorful Instagram feed, made up of squares of women—all of whom would be regarded as conventionally attractive and well-dressed—with no idea they were being photographed.

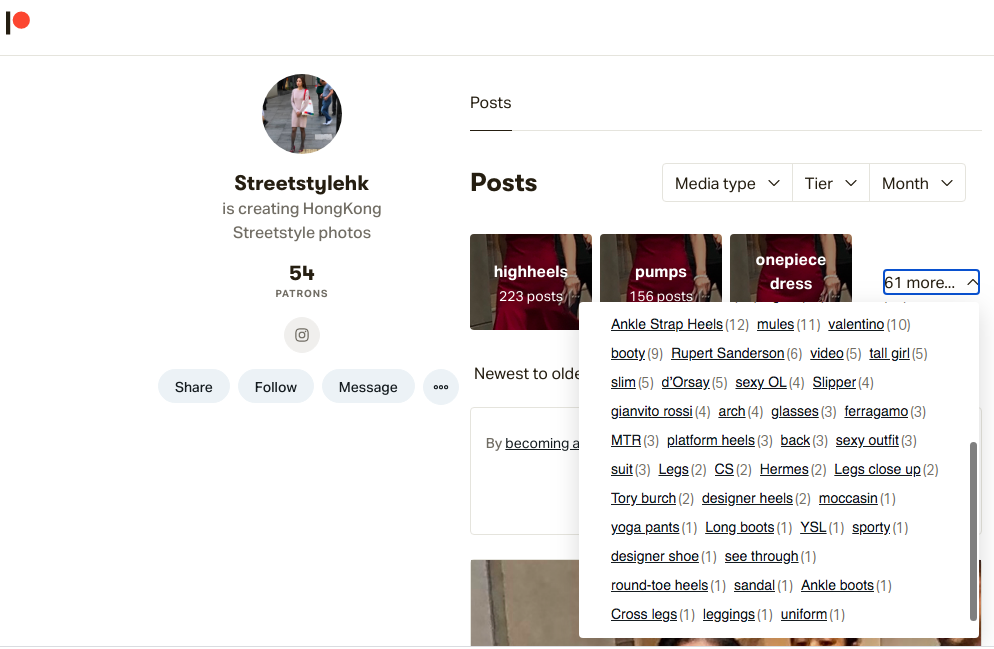

At first, when a friend sent her a screenshot of her picture, G. (who asked to go by an initial) thought @streetstylehk was an amateur fashion photography page. For a moment, she was even a little amused. But then she saw the lewd comments left by anonymous accounts, and that more than 1,300 photos, including of her, were posted on a Patreon page for a monthly subscription fee of US$5.

“I just feel like this is quite wrong,” she told Coconuts. “It’s just not very comfortable.”

During the course of this story’s reporting, Patreon removed the account after Coconuts emailed to ask if it violates any community guidelines. It confirmed later that the account had been deleted, but declined to elaborate.

Shortly after it was removed, and as Coconuts was reaching out to the owner over Instagram, all the photos on the Instagram account were taken down and a new line was added to its bio: “Stay tuned ! Come back soon!”

Disturbing comments

@streetstylehk is not the only Hong Kong-based Instagram page that shares unsolicited photos of women. At least half a dozen of such accounts exist, but @streetstylehk—a private page which had over 3,520 followers since posting its first picture almost four years ago—was, by Coconuts‘ research, the largest.

Their photos, most of them taken in Central, didn’t attract many comments. But when they did, they were shallow at best, and crude and sexually aggressive at worst. “I want to penetrate her from behind,” a comment on a photo of a woman in a modest knee-length, mustard yellow dress, read.

In another picture of two women walking, an account with no profile picture, posts or followers wrote: “One photo, two girls to f***.”

In response to an Instagram message from Coconuts, @streetstylehk said in English: “i like woman with good dressing style, so i share that. No sexy and porn.”

The account stopped replying to requests for comments after the Patreon page was removed.

‘A kind of pornography’

The pictures on @streetstylehk, and other similar accounts, did not contain any nudity or racy content. But it’s exactly the candidness of these photos that underscores the everyday sexism that is still rife in Hong Kong.

Katrien Jacobs, an associate professor of cultural studies at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, called the photos “a kind of pornography.”

“It’s the opposite of naked images. It’s people who wear high fashion and are well-dressed. But it’s still expressing a male view, a male gaze of what contemporary women should look like,” she said.

The instinctive, split-second decisions of who to photograph, and who to skip, result in a finely curated feed of females that doesn’t represent reality.

Jacobs added: “[These photos are] a fantasy, just like naked women in porn are a fantasy image.”

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data told Coconuts that since the photographer is not publishing data that would allow the photo subjects to be identified, like their name or their phone number, no privacy laws have been breached.

Before the Instagram page was removed, Coconuts reached out to the Facebook-owned company to ask if the account’s behavior was at odds with the platform’s guidelines, attaching screenshots of a few posts and some of the more explicit comments.

A manager from the communications team said those comments were deleted because they were “clearly violating,” adding that “bullying and harassment has no place on Instagram.”

Where is the feminist uprising?

In Hong Kong, the use of online platforms to share unsolicited pictures of women underscores a culture of sexism and gender discrimination in the city.

When the #MeToo movement swept the US and spread across the world in 2017, local athlete Vera Lui was inspired to go public with accusing her ex-coach of sexually abusing her when she was 13—and received little more than the obligatory media coverage. Online, some even said she was spinning a tale for fame. (In a trial the following year, the court magistrate said he did not know what #MeToo meant, and asked if it was the name of a website.)

And it wasn’t until last year when the city held its first #MeToo rally, a response to police’s alleged sexual harassment of pro-democracy demonstrators. For female protesters who had come forward with disturbing accusations of sexual threats and violating strip searches at the hands of police, the rally was a welcomed moment of vindication and solidarity.

“I think it was a very important development for Hong Kong. And as people often say, social movements push other values forward,” Jacobs, the CUHK professor, said.

But while it marked a key milestone for Hong Kong, bringing the issue of gender inequality out of academic circles and into the public, it failed to spark wider, overdue dialogue about gender issues in the city at large.

In fact, the very demonstrators who attended the #MeToo rally could very well be the same people guilty of pushing a sexist culture. Female political activists have spoken about being on the receiving end of unsolicited sexual comments, but their concerns are sometimes dismissed by pro-democracy supporters who don’t wish to see the political movement sidelined.

On the forum LIHKG, a common refrain whenever police are accused of violence against women is “女權L去晒邊,” meaning “where have all the f**king women’s rights activists gone.” The phrase accuses feminists and women’s rights groups of being hypocritical, staying silent about abuse when they don’t want to wade into politics.

To Angie Ng, the posting of unsolicited pictures of women online in a way that unapologetically sexualizes and objectifies them is “not a surprise” in patriarchal Hong Kong.

A lack of awareness about gender inequality is exactly what prompted Ng to bring Slutwalk, an international movement that marches to raise awareness about sexual violence, to the city in 2011.

“Hong Kong is still a very gender unequal society,” she told Coconuts. SlutWalk has organized marches in Hong Kong every year except 2015, 2019 and this year, and if the virus situation allows, Ng hopes to revive it in 2021.

“It’s important to have hope and be able to envision positive change. Societies are dynamic, and social change requires time,” she said.

Ng added that there are different levels of acceptance of the feminist movement even in western societies, not least in relatively more conservative Hong Kong.

Activists and academics who spoke with Coconuts agree that what’s most important at this stage is dialogue—about the taboo around sex, stubborn denial that gender inequalities exist, and the harmful victim-shaming attitude that dissuades women from speaking out in the first place.

Oftentimes, though, conversations don’t always go the way they’re hoped to.

When G. told one of her male friends that her photo had been posted on the Instagram page, and how it was sharing secretly taken photos of other women too, he laughed.

“He was making jokes,” G. said. “I was a little bit upset about that. I don’t think he noticed I was being serious.”