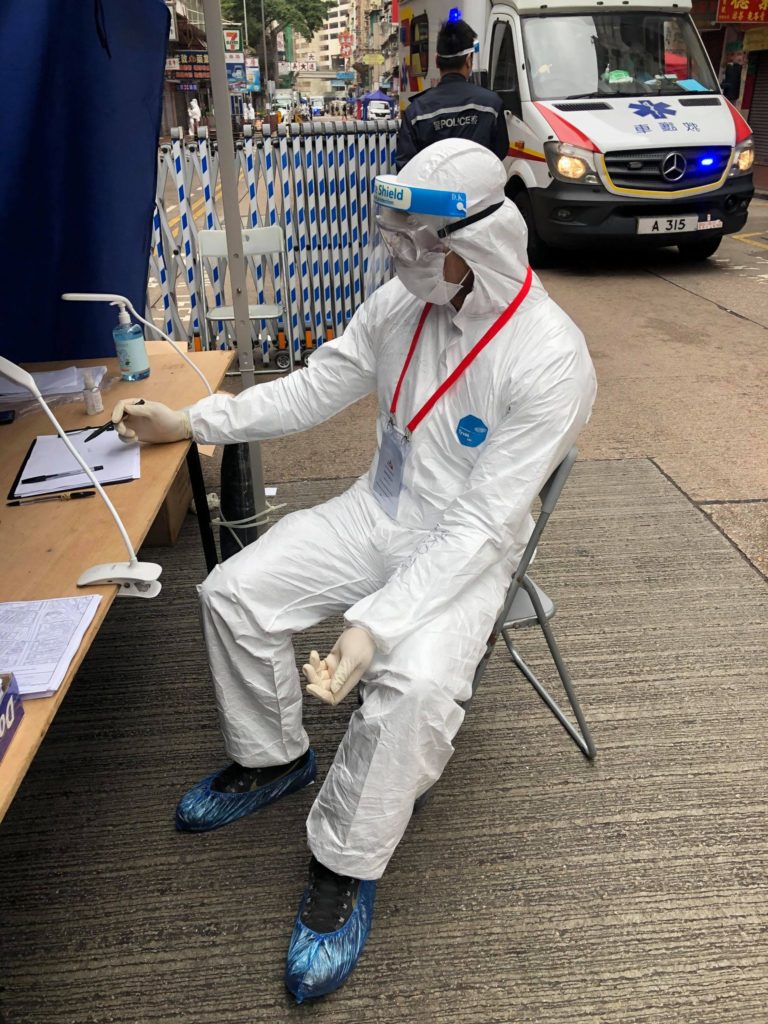

Suited up in medical-grade protective gear, Jneth Rana got ready for another day at the new epicenter of the city’s COVID-19 outbreak. It was the morning of Jan. 23, hours after authorities locked down a virus-hit part of Jordan, and the Nepali-born Hongkonger was waiting on instructions at a community center nearby.

A representative from the Home Affairs Department (HAD) doled out duties to Rana and the other ethnic minorities who had gathered. Some were to visit COVID-infected buildings, via vans arranged to transport them, and knock on doors to ask occupants if they had taken the virus test.

Food packs had to be sorted for the thousands of residents confined to their homes for two days. And there were leaflets about penalties for not getting tested, to be passed out to anybody still roaming the streets.

Yau Tsim Mong district, where Jordan is, has the highest population of ethnic minorities—mostly South Asians from India, Pakistan and Nepal—in Hong Kong. As residents said they were being kept in the dark about the outbreak, the language barrier between them and the local community had never proved so crippling.

The 48-hour lockdown, and the mass operation to carry out thousands of tests leading up to it, was the government’s strictest and most sweeping COVID-19 measure since the outbreak started.

Behind the effort were dozens of ethnic minorities who served as interpreters on the frontlines, putting their health at risk even as media outlets ran race-tinged headlines blaming South Asians for spreading the virus.

‘You don’t have to worry’

Rana, a 26-year-old freelance designer, worked as an interpreter almost every day the week of Jan. 18, logging eight-hour shifts at a time. When authorities locked down a block in Yau Ma Tei the following Tuesday, she was there too.

“I came into contact with positive cases, so obviously I was pretty scared,” she told Coconuts.

But Rana thought back to one afternoon, when she knocked on the door of a Nepalese woman in her 70s. She was alone, her son, daughter-in-law and grandchild out working till late at night. The sight of two strangers head to toe in protective gear intimidated the woman, who was unaware that she was living in the middle of a virus hotspot.

“Her face was in shock,” Rana said. “She was panicking and I had to greet her in my language, ‘Namaste, you don’t have to worry grandma.'”

Read more: ‘No Indian/Pakistan riders’: Deliveroo closes customer account over racist comment

The woman asked her a barrage of questions, like where she can get tested and what happens if she tests positive.

“She was very grateful that I was there to talk to her in her language. It made me feel like this was a good decision, me coming out to the frontlines,” Rana added. “It was very rewarding.”

According to the government, the HAD arranged 50 interpreters fluent in ethnic minority languages including Nepali, Urdu and Hindi to assist during the two-day Jordan lockdown.

Rose Limbu, a Hong Kong-born Nepali, began working as an interpreter before the lockdown began. Stationed at a COVID-19 testing center, the 22-year-old student translated for ethnic minorities forced to use an online booking website only available in Chinese and English.

“There was a relief on their face when they saw that someone Nepalese could help them,” Limbu said, adding that many older Nepalese and asylum seekers did not speak Cantonese, and knew only basic English.

The government’s actions in addressing the concerns of ethnic minorities have been more performative than practical, Limbu added. “There was a government advertisement on TV saying, ‘We are one, let’s work in harmony.’ But that hasn’t change anything.”

Also among the interpreters was Hong Kong-born Pakistani, Burak Usman Mehr. His decision to work as an interpreter was spurred by a comment made by the head of the Health Promotion Branch at the Centre for Health Protection, Raymond Ho.

‘A scapegoat’

At a Jan. 18 press conference, Ho said ethnic minorities like “gather[ing] with fellow countrymen” and are at higher risk of infection, a remark many called racist and insensitive.

“People just wanted a scapegoat and they found us as easy targets as we don’t speak out,” Mehr told Coconuts.

Paired with a worker from the HAD, the 24-year-old student—who speaks Hindi, Urdu, Cantonese and English—spent over a week weaving in and out of the dilapidated buildings that populate the area.

They started at the top of a building and made their way down, stopping at every floor to knock on doors and ask residents if they had taken the virus test. If they weren’t home, they left leaflets in ethnic minority languages at the gate.

Many of the flats had been subdivided into multiple units. “The old buildings were really dirty,” Mehr said, adding that there was a “putrid” stench in some stairwells.

By the end of the two-day lockdown, authorities had tested over 7,000 residents. The fences that cordoned off the area came down and traffic resumed—but Judy Gurung knows the work isn’t over.

As the Democratic Party’s community coordinator of ethnic affairs, the Nepali-born Hongkonger receives dozens—sometimes over a hundred—messages a day from residents. One Pakistani family in quarantine complained about not having Halal food. A Nepalese man on Reclamation Street, where some of the outbreak’s first COVID-19 cases were reported, sent her pictures of a trash-filled alley by his building.

The HAD only set up a hotline in ethnic minority languages in the third week of January, and since then, she’s received fewer calls for help. Before that, Gurung told Coconuts, “I was the 24-hour hotline.”

More lockdowns in sight

Hong Kong, which had so far avoided the strict restrictions common in places harder hit by the virus, was caught off guard by the Jordan lockdown. But it was soon understood as the first of many to come—in the 11 days since then, authorities have mandated 13 lockdowns across the city.

The recent lockdowns have been smaller in scale, targeting just a block or two, and shorter too. Authorities cordon off the area in the evening, aiming to have everybody within it tested—and results ascertained—by around 7am the next day.

“Depending on the development of the pandemic,” Chief Secretary Matthew Cheung said Monday, “we expect to mount at least one operation per day.”

The ethnic minority interpreters who worked during the Jordan lockdown have also helped out in the smaller seal-offs, including in Yau Ma Tei and Tsim Sha Tsui, where there are also significant South Asian populations.

Given the “ambush” nature of the strategy—no warning is given ahead of the lockdowns, a tactic the government employs so that residents cannot flee in time—the interpreters are asked the night before, or even the day of, if they would be available to assist. They’re only told the location at the last minute.

They hope their efforts behind the scenes can help vulnerable ethnic minorities, whose needs have long been ignored by society, better navigate the outbreak.

But Rana emphasizes: “I’m not just serving my community, I’m serving the whole of Hong Kong.”