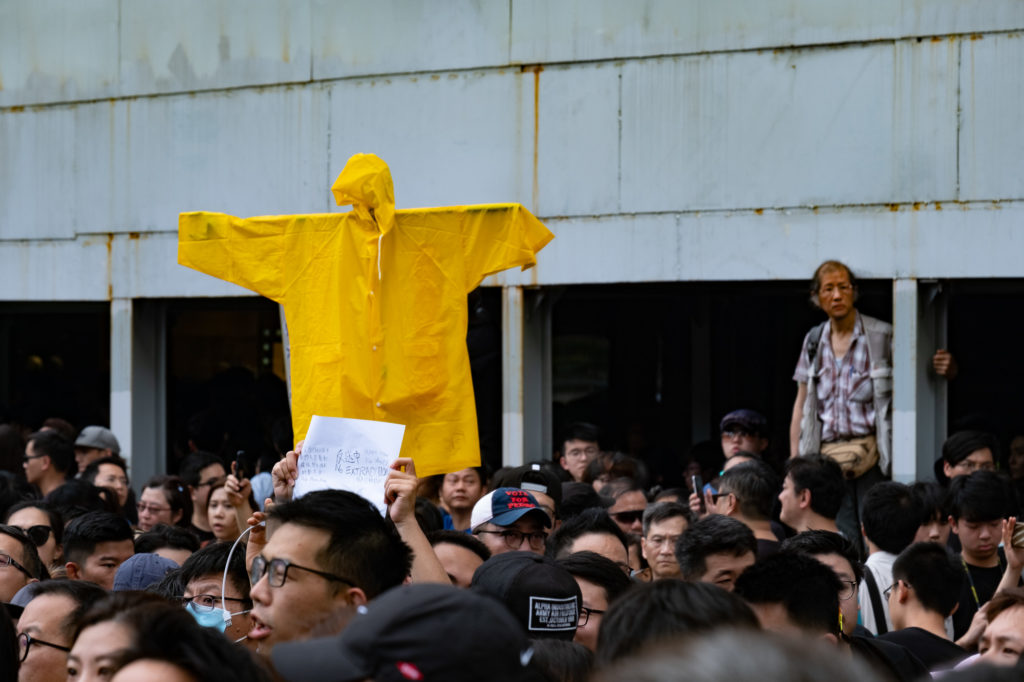

Exactly three years ago today, M (who wishes to be just known by her initial) was one of the 2 million people estimated to have taken part in the largest demonstration in Hong Kong’s history, meant to voice opposition against a controversial extradition bill.

“We arrived in Tin Hau at around 4 or 5pm and there were so many people that we couldn’t find the end of the queue to enter Victoria Park — the starting point for the demonstration,” she said, recalling there were people of different age groups there wanting to make their views heard.

“It was already 9 plus 10pm by the time we reached the end point in Central.”

The protest was part of a wave of demonstrations that were set off by a proposed bill that would have allowed extraditions to jurisdictions including mainland China, which some feared would be used to target political activists.

Authorities sought to allay fears by saying suspects accused of political and religious crimes would not be extradited, but that did little to reassure the public.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam attempted to diffuse tension the day before the protest by saying she would “suspend” the bill.

But many still took to the streets on June 16, 2019.

Police estimated that 338,000 people followed the original route of the demonstration at its peak. The rest of the protesters spilled over to four nearby roads.

Many also participated in the protest to respond to what they believed was the excessive use of force by the Hong Kong Police during a related demonstration on June 12, 2019 and to remember the death of Marco Leung, a disheartened protester who died from a fall a day before.

Despite the somber circumstances leading to the protest, M recalled the hope and warmth she felt.

“That day, I realized a lot of Hongkongers really love Hong Kong,” she said.

“I was also right next to the ambulance that was filmed coming through and had people parting like the Red Sea so that emergency services will not be affected. The scenes are all still very vivid.”

But things are very different three years later.

It has been a long time since Hong Kong saw mass protests on its streets, with authorities rejecting any applications for demonstrations in recent years citing concern about the spread of COVID-19.

Many key figures from the protest movement have also been arrested for crimes such as taking part in an unauthorized assembly or violating the Beijing-imposed National Security Law, which critics say curtails freedom of speech.

M is no longer in Hong Kong, having moved to Canada in January 2021.

While she did not leave Hong Kong solely because of the political situation in the city — her spouse is a Canadian and they have had plans to migrate for years — M said the government’s handling of the protests and the ensuing development definitely sped up the process.

Even though she is thousands of miles away from Hong Kong, M said a feeling of unease still creeps up whenever it is June — when the protests gained momentum three years ago.

She said she still follows what is happening in Hong Kong on social media closely.

Moreover, she said she would attend some of the gatherings or demonstrations in Canada to commemorate the protests.

“My friends and I watched “Revolution of Our Times” when it was showing in Canada in February,” said M, referring to the film about the protests in Hong Kong in 2019 and 2020.

“We cried again. It’s like re-experiencing the trauma.”

She added that such times also brought back painful memories of living in Mong Kok East, where she frequently heard police firing tear gas grenades.

But, being only able to look at what is happening in Hong Kong from afar now, M said she feels helpless.

“I look at such ridiculous policies being implemented in Hong Kong and there is nothing I can do,” she said.

“I miss the freedoms we had in Hong Kong, when you could freely express your views on Facebook — whether they are for or against the establishment, when you had media outlets with different political stances, when we could watch ‘Headliner’ on RTHK.”

That TV show, which contained satirical sketches that were critical of the government, was suspended indefinitely after the Communications Authority warned it for “insulting” the police in an episode.

M also said she sees no future for the city, where many of her friends have no expectations for the future and are living like they are just “surviving” and “getting to and off work.”

While many were critical of the violent tactics employed by some protesters — which led to the arrests of many young people and the passing of the National Security Law — M, who did not participate in the violent protests herself, believes they played a part in ensuring that the now-withdrawn bill would not be passed.

Choosing to stay

While many have left in the past three years, some chose to stay.

Patrick (a pseudonym) is one of those who have remained in Hong Kong.

He said he has chosen to do so for family and work reasons.

“There’s definitely a possibility of leaving Hong Kong. It’s something that has been on my mind these few years,” he said.

“Hong Kong is now a place with shrinking freedoms, while civil participation has decreased majorly. There is no room for not just opposing voices, but even second opinions.”

Authorities and those within the pro-establishment camp have lauded the National Security Law for putting an end to protests and clashes between demonstrators and the police, which took place almost every day at their peak, and returning Hong Kong to order.

But Patrick said questions about the bill and issues related to the authorities’ handling of the situation — including the police’s controversial treatment of protesters — and the city’s democratic development are still not resolved after three years.

“I’m feeling very suppressed,” he said.

“It’s heartbreaking and dispiriting.”

As we enter this particularly sensitive time of the year, Patrick said he still commemorates the special dates privately.

“When it comes to special dates like June 9, June 12 and July 21, I still remember them in my heart, and will share some essays or posts about what happened on my social media accounts, but I make sure they can only be seen by my friends,” he said.

“I hope that by sharing them, we can be reminded of what happened and do not forget this piece of history.”

While “Revolution of Our Times” can now be seen online in Hong Kong, Patrick said he has not watched it out of fear of both reliving the experience and potentially breaking the law.

“I’m scared that I can’t handle the emotions and pressure,” he said.

For him, the future of Hong Kong is bleak.

“We no longer have a vibrant civil society. We used to have a multitude of voices but now everyone is like a yes-man,” he said.

“Without diversity in society, we can’t have innovation and cannot attract or retain talents.”

Seeing in a new light

For some people, it is only later that they become more aware of what was happening in Hong Kong during those months.

Q (who wishes to be just known by her initial) is a foreigner who was working in mainland China when clashes first broke out in Hong Kong that June.

“I remember there were a lot of people in the WeChat groups I was in calling the protesters ‘useless youth’ or ‘thugs’,” she recalled.

While she was skeptical of these claims as she had vaguely heard from other foreign friends about how the freedoms of Hongkongers could be affected by the passing of the bill, she did not find out more as she was busy with other matters and it was troublesome to bypass China’s firewall.

A month later, she was in Hong Kong for personal reasons.

“I remember seeing the Lennon Walls in Hong Kong and even taking photos of them,” she said.

“I really admire the passion of Hongkongers in defending their freedom of speech.”

Because she was busy with other matters, she did not go out to the streets much and did not witness any of the clashes.

Q began a program at a Hong Kong university in September 2020.

“Because of COVID-19, I couldn’t come to Hong Kong and was taking Zoom classes while on the mainland,” she said.

“I remember this very strong feeling of fear among my Hong Kong classmates. From the way they spoke, I could tell they were very sad and dark. Everyone was talking about migrating and I didn’t really understand why.”

It was only in January 2021, when she arrived in Hong Kong, that she learned more about what happened in the city during those months.

She started reading up and talking to Hongkongers she met about the protests, arsons and the police’s controversial handling of the demonstrations — including what some believed was excessive use of violence and the way some officers went undercover as protesters.

“I was very shocked,” she recalled.

Witnessing the removal of the “Pillar of Shame” and “Goddess of Democracy” sculptures in the University of Hong Kong and the Chinese University of Hong Kong, respectively, solidified her belief that freedoms were being eroded in the city.

“I also befriended someone who has kin in jail. Seeing all this happening with my eyes, I really believe in the concerns of the protesters,” she said.

Q said she no longer plans to go back to the mainland after graduation, but she hopes to share more factual information about what happened in Hong Kong with her friends there.

“There is a lot of ‘he said, she said’ but some are facts that happened, which have been documented or which I have experienced,” she said.

“I hope I can let more who are interested know what happened here.”

Q said she has since fallen in love with Hong Kong and plans to stay here for a while.

But she said she will leave if she no longer finds it safe here.

“I am fortunate that I can leave easily as I am a foreigner, but I feel sad for locals who find it difficult to leave or might not want to as it is their home,” she said.