Amid the run-down splendor of Bangkok’s Chao Phraya River, a band of brilliant green now links the capital’s two halves.

The Chao Phraya Sky Park, a verdant garden brought to life in a concrete void, may be seen as a fleeting exception to a city doomed to dysfunction, a mirage of a Bangkok that will never be. But those who brought it to reality hope it’s an exclamation point declaring a more optimistic future.

Designed to be a “quick win” for Bangkok’s urban-planning ambitions, the elevated greenway cost only THB122 million (US$3.9 million), or 6% the equivalent spent on a similar, now-abandoned London project. And while it has seized the imaginations of those who dream of a more livable capital, the design wonks behind it hope it’s a model for future successes.

“If you’re not persistent, projects like these can’t be achieved,” said Niramon Serisakul, a founder and director of Urban Design and Development Center at Chulalongkorn University. “With its completion, other potential projects will follow too.”

‘Garden bridge’ across Bangkok’s Chao Phraya opens soon

Niramon’s urban planners, along with designers from firms N7A Architects and Landprocess and the cooperation and support of City Hall and the Highways Department, brought the garden bridge to life atop an unfinished skytrain project abandoned three decades ago.

In addition to linking the old quarter to Thonburi, the bridge, she hopes, can also connect Bangkok to better future by example. As a totem for the political will necessary to make more projects possible, with cascading benefits that make the city more walkable, spread its prosperity more equitably, improve health and better the environment.

“Wealth won’t only cluster at shopping malls but will spread into streets and sois,” she said. “We plan to study how this sky park brings economic benefits to nearby communities.”

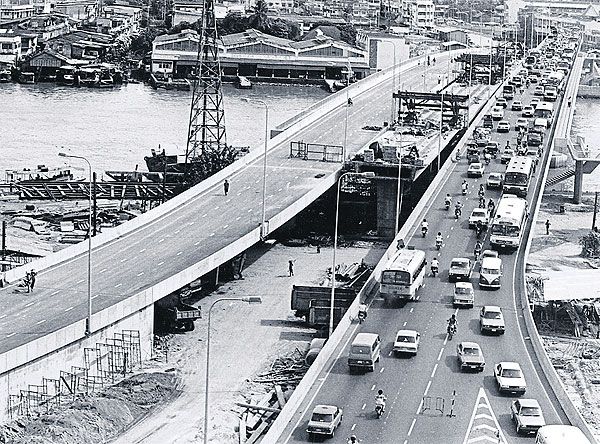

A file photo of the “amputated bridge,” as the abandoned Lavalin Skytrain project is called. Photo: Urban Design and Development Center / Courtesy

Her center is Bangkok’s first urban agency seeking to engage a wide range of parties in the government, private sector and civil society to affect change by coming up with cool solutions. In its eight years, it has spearheaded several urban initiatives including the Yannawa Riverfront, a promenade meant to reclaim the river for the public; and Active River Station, which redesigns and renovates its piers.

During a recent interview at its modest office on Si Phaya Road, Niramon shared her vision, informed by Eastern and Western thinking, of what could come from a greener, safer and more pedestrian-friendly city; the barriers to it happening; and how the public’s voice can be heard.

As she did, a stray kitty rescued Christmas Eve from the sky park and named after Jules Verne’s Passepartout paced curiously around the new guest before eventually settling into a chair to listen. Our lightly edited conversation follows.

Walk us through how the Chao Phraya Sky Park project began?

Bangkok’s governor (Aswin Kwanmuang) said he wanted a model project that would be a quick win, one that executes with high impact and high visibility. Plus, there were fewer hurdles: We didn’t have to evict any residents.

We surveyed the Kadeejeen and Khlong San communities over 60 times and, on about the 40th survey, [Buppharam community leader Pradith Huaihongthong] walked up while I was having coffee and said “Ajarn, there’s the amputated bridge. Why don’t we use it?” At the time I had no idea what it was, although I drove past it almost every day. I saw it so often that I overlooked it.

What were its inspirations?

The idea of an elevated garden bridge has been around since the 19th century. London’s Garden Bridge, The High Line in New York and the Viaduc des Arts in Paris were inspirations. It’s nothing new in terms of structure and its reuse, but the point was this: Would book theories work in practical reality? How do you convince people to buy into it? These were the real issues, and we eventually made it through.

Speaking of barriers, what were they and how did you overcome them?

One of the difficulties was working around the old town area, which has many layers and small land plots. You have to talk to so many people; thus, the complexities are high.

The first four years were spent talking to the organizations involved, such as the Department of Highways, who at first didn’t understand the concept. Their concerns also included safety, such as, what would pedestrians be doing up there? Will it be safe? But at the same time, they are also interested in the project. I understood them, because nothing ever succeeded before this project. It was the first of its kind, so it was difficult.

I’m grateful for my professor who taught me about participation and deliberative democracy. Building relationships and a sense of ownership with local residents helps a lot. At first they raised a defensive guard because they didn’t agree with the project, while the governmental organizations had their own issues. But later we all came to a mutual understanding. It’s fair to say that a participatory process is the best planning method we’ve got.

If your team was omnipotent, and resources and land rights no issue, what would you make happen immediately?

I want to focus on improving the city’s walkability. It should be dern dai, dern dee (“easy walking”). Pleasant to walk, convenient to walk, and safe to walk. If we can execute on those, the city would be much better. Walkability is the shorthand that can change so many things in an urban city like Bangkok. From our surveys, Bangkokians are willing to walk up to 800 meters, which is about the same as pedestrians in America (805 meters) and Japan (820 meters). Even in Singapore, where the climate is similar to Thailand, when you see a lot of trees, you want to walk, right?

Improving walkability would help with environmental problems too. For a few years now we’ve struggled with PM2.5 air pollution, which is caused by vehicle exhaust. You can see some walkable cities have good air quality; therefore, if we can make the city more pedestrian-friendly, this problem would no longer be a danger to us.

Bangkok air ‘healthy’ only 4 of year’s first 100 days; air pollution found to make COVID deadlier

To sum it up, if we can improve walkability, our health will improve, and economic opportunities will follow.

What can people, the Thais and immigrants who love this city, do to affect change?

I think we need to question things. We can be dissatisfied, but we need to be reasonable too. Can we start planting trees at home to support a greener city? Admittedly, citizens can help only a little bit, but if they want large-scale change, the authority lies with the government.

I think online platforms these days are so powerful. People use social media to call for action, even to criticize, and I think this helps a lot. You know, this project was achieved partly because, when we organized the last conference […] we had 700 reservations and 300 walk-ins. The hall was packed. The governor was impressed and convinced that a lot of people were interested and supported the idea. The next day I had a chance to talk to more officials.

How does Bangkok compare to other cities you’ve lived in?

Since I studied my master’s degree and doctorate in Japan, I learned many things: endurance, negotiation and community engagement, to name a few. I also spend a lot of time working and living in France too, and I found that France is like the queen of urban design. It has case studies from every era to learn from. Meanwhile, Japan’s design taught me about processes. Japan is obsessed with researching and studying. Japan tried to recover from World War II and it built awareness on many things, from the economy and environment to human rights.

So for design, I like Europe. But I’m also a fan of Japan in terms of process.

Singapore is also cool in their own way. The first prime minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, was very cool with his “garden city” vision. I don’t know how he came up with it. In the 1960s, he used greenery to build a brand for the city. The idea is even far ahead of England, but Lee adapted it with a Chinese-style twist, connecting greenery with the local finance and economy, which is so cool.

The Chao Phraya Sky Park is now open to the public. It connects Phra Pok Klao Park on the Phra Nakhon side to the Chaloem Phrakiat Forest Park on the Thonburi side. Pedestrians may enter and exit from both sides.

Additional reporting Todd Ruiz

Related