By Samanachan Buddhajak / China Dialogue. Photos: Luke Duggleby

“We don’t want our brothers and sisters in other parts of the country to face the impacts we have been facing,” says Thanawan Kainok, addressing a panel discussion on the ‘Past, Present and Future of Potash in Isan’ in Wanon Niwat district, in north-east Thailand’s Sakon Nakhon province.

In 2015, the China Mingda Potash Corporation, a Chinese company registered in Thailand, received a licence to survey this rural area for potential sites to mine potash – naturally occurring salts rich in potassium and sodium. To date, while the company has explored several locations, they are yet to commence commercial mining due to strong opposition from local communities in the area.

Thanawan travelled more than 300 kilometres to join the discussion, held in April 2023, from her community in Dan Khun Thot district, Nakhon Ratchasima province. Dan Khun Thot is the location of the only active potash mine in Thailand, and has suffered extensive salinisation of land and water, allegedly as a result of mining activities.

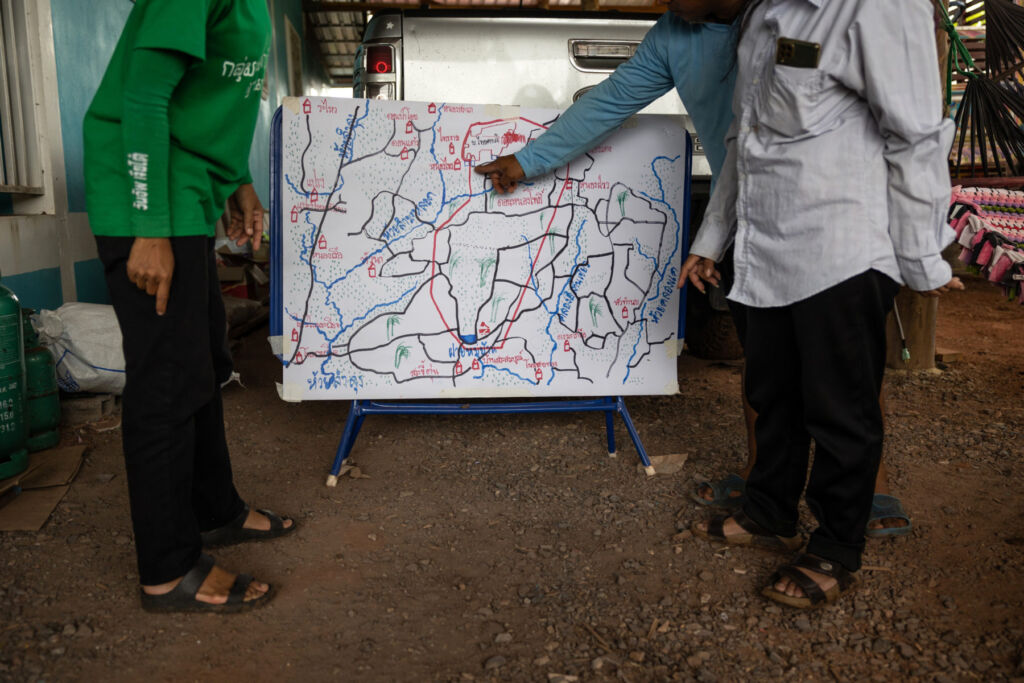

Villagers in Wanon Niwat worry that a new potash mine could contaminate waterways that tens of thousands of people depend on for agricultural and household use with harmful chemicals and salt. In 2015, they formed the Wanon Niwat Preservation Group, which opposes potash mining with demonstrations, petitions, and direct action, such as physically blocking the company from surveying the area. As a result of the latter, the company filed several lawsuits against community members in 2018, accusing them of defamation and demanding compensation.

Wanon Niwat is one of three locations in north-east Thailand where companies have been attempting to mine potash, but have yet to start commercial extraction.

While potash is mainly mined for potassium, which is used to produce fertilisers, the sodium it contains could soon prove equally attractive. Researchers at Thailand’s Khon Kaen University have recently successfully developed rechargeable batteries that use sodium, rather than lithium. This new technology, which is also being developed elsewhere in the world, looks set to make a big impact on the electric vehicle (EV) industry in particular. Sodium is cheaper and more readily available than lithium, and its use in batteries could help make EVs more affordable and promote their more widespread adoption. The Thai government is keen for this to happen, but anti-mining advocates worry it may trigger a boom in potash mining.

Growing pressure to tap Isan’s rich potash reserves

The north-east of Thailand, a region also known as Isan, has a long history of salt-making. Potash was first discovered in the area in the 1970s. While the size of Thailand’s reserves is not clear, the government claims they amount to the fourth largest in the world. Canada has the world’s largest known reserves, at 1,100 million tonnes, followed by Belarus and Russia at 750 million and 400 million tonnes respectively. There has been interest in mining Thailand’s potash since the 1980s, but very little headway has been made until the last few years, mainly due to a lack of financial viability and legal restrictions, as well as local opposition.

The recent push to mine potash is closely tied to changes in the global market for fertilisers. Thailand currently relies heavily on imports, bringing in more than 736,000 tonnes of potassium chloride in 2022 according to Thai customs data. But disruptions to trade in the commodity due to sanctions imposed in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the suppression of peaceful protest in Belarus resulted in a significant rise in potash prices in 2022.

“The [Thai] government has been saying that the [mining] projects will reduce the import of potash and in turn reduce the price of fertiliser in Thailand,” says Santiparp Siriwatthanaphaiboon, a lecturer at Udon Thani Rajabhat University. Santiparp says the country has the potential to produce an estimated 3 million metric tonnes of potash per year. This exceeds Thailand’s current demand, leaving a healthy chunk that could, he says, be sold to China.

Despite having its own potash reserves, China, with its vast agricultural output, is the world’s third largest importer of the commodity, bringing in more than 7.5 million tonnes of potassium chloride every year, mainly from Russia, Canada and Belarus. The country has long eyed Thailand’s reserves as a potential alternative source closer to home. In 1997, the two governments signed an MOU on Chinese investment in potash mining in Thailand. A few years later, in 2004, the China Mingda Potash Corporation applied for a licence to explore for potash in Wanon Niwat.

It wasn’t until after Thailand’s military coup in 2014 that this exploration licence was approved, however. Keen to make more economic use of the country’s natural resources, the new military government also granted mining concessions in three locations in the north-east provinces of Chaiyaphum, Udon Thani and Nakhon Ratchasima. So far, mining has only started in one of these locations – the Dan Khun Thot district project in Nakhon Ratchasima, operated by the local Thai Kali Company.

Dead soils and salty water

“I will keep this piece of land as it is, to be evidence of what the potash mine has done to the villagers,” Thanawan Kainok says while walking on salt-encrusted land back home in Dan Khun Thot. This piece of land, abutting the mine’s border fence, used to be a paddy field. After the potash mine started operating in 2017, community members say salt began seeping into the area’s water sources and the soil became so salinised that nothing would grow.

A process called solution mining is being used to extract the potash here. This involves injecting large quantities of water underground to dissolve the potash salts. The resulting brine is then pumped back up to the surface into large ponds, where the water is slowly evaporated off to leave behind crystals of potassium and other salts. The entire process is very water intensive, and the risk of contaminating nearby water sources is high.

Within two years of Thai Kali commencing mining operations in Dan Khun Thot’s Nong Sai sub-district, residents of the adjacent village of Sai Ngam began to see their crops fail, and traces of salt beginning to appear in the soil surrounding the mine.

What had been productive farmland growing rice, mangoes and corn is now covered with the white residue of salt for much of the year. Dead trees and bushes stand where healthy ones once grew.

“I always thought that they [the mining companies] would bring development to us. I was really shocked to see this much negative impact,” Thanawan says.

At the villagers’ request, the Environment and Pollution Control Office, a Thai government agency, tested soil and water samples from around the mine in May 2022. It detected very high salinity – so high that residents have noted erosion to their walls and buildings caused by the salt.

Krue Kainok, who lives in a village located more than 10km from the potash mine, says that running water in his village became salty in 2019. “We were showering and suddenly felt itchy. The shampoo no longer produced bubbles. When we tasted the tap water, that’s when we knew that the running water had become salty,” he says, explaining that salinised water from the area around the mine flows down through natural waterways into the public pond used by his village.

The villagers bought drinking water for almost a year before they demanded someone take responsibility. Eventually, Thai Kali laid pipes to connect the village to another water source, but the price they had to pay for water ballooned.

In early 2022, when the company started to explore other possible mining locations in the area, residents in the village of Sa Khi Tun quickly saw environmental impacts in the immediate vicinity of a test site. Rice that once grew in abundance stopped growing, and fish in a nearby pond died. Fearing they would face the same fate as Sai Ngam village, residents came together to form the Dan Khun Thot District Preservation Group to oppose the mine and demand compensation. Thanawan, who had returned home from working in Bangkok during the Covid-19 pandemic, decided not to go back to the capital, and became a leader of protests against the mine.

“If we don’t fight, the impacts are going to get worse,” Thanawan says. Thai Kali bought much of the land surrounding the mine from residents, but Thanawan refused to sell hers. “We are fighting so people will see what is happening to us. We want to be an example so the same thing will never happen in other areas in Isan.”

Electric cars and a new reason for more potash mining

In 2021, the Thai government announced its ambitious ‘30@30’ vision, which aims to ensure that 30% of the country’s vehicles will be electric by 2030. This push has put wind in the sails of Thai efforts to develop affordable rechargeable batteries using sodium, a cheaper alternative to lithium. The sodium-ion batteries so far developed by Khon Kaen University – the first of their kind in Southeast Asia – are not yet ready for use in electric vehicles. But the government hopes they will play a key role in the development of Thailand’s own EV battery industry. It seems there are also hopes this will, in turn, boost the potash industry. Official communications on the subject often mention the country’s potash reserves as a source of sodium.

Similarly, internal efforts to push potash mining also point to the potential growth in demand for sodium thanks to this new type of battery. This can be seen in a Ministry of Finance document presented to cabinet in January 2023, which states: “There are investors in energy who are interested in investing in the [proposed] potash mine in Chaiyaphum province. These investors are not interested in producing potassium fertiliser but in using potash as a raw material to produce batteries for EVs.”

However, experts have questioned the need for new potash mines to meet demand from the EV industry.

Nonglak Meethong, head of the sodium-ion battery research team at Khon Kaen University, explains that the technology needs very pure sodium. New mines focused primarily on potassium production may not be able to provide this.

The battery they developed used sodium extracted from rock salt mined in Thailand. At current levels of demand, Nonglak does not believe an additional source of the mineral is needed. But demand is likely to increase substantially over the next decade, she says.

“The technology to produce batteries from sodium will be coming in for sure, which is good progress. However, we will need to manage the resources and control the environmental impact,” says Nonglak, noting the need to limit repercussions on communities who live near mines.

Lertsak Khamkhongsak, an anti-mining advocate and founder of activist group The Project for Public Policy on Mineral Resources, agrees that current quantities of rock salt mined in Thailand are adequate for the needs of the battery industry. He fears EVs are being used as a green excuse to push for more potash mining.

Claiming you are trying to be environmentally friendly is a way to get projects “approved more easily,” says Lertsak, adding that “what happens in reality is different”. “At the end of the day, potash will mostly be used by China to make fertiliser.”

“There needs to be a more complete explanation of how they will take care of the pollution and [map out] appropriate mining areas, not just coming out and saying that we will have enough materials to produce batteries,” Lertsak says. “Even with just the potash mine in Dan Khun Thot district, there are already many impacts. If there is more demand from other industries, how will they be able to control the impacts?”

China Dialogue reached out to the Thai Kali Company for their response to the issues raised in this article, but had not received a response by the time of publication.

This article originally appeared in China Dialogue.