Almost 40 years ago, Nok took a train from Udon Thani to arrive at Bangkok’s Hua Lamphong Station for the first time. His first job was gluing shoes for THB50 a day. He slept in a fetid rathole so he could send money home.

Through years of hardship set before a backdrop of economic and political crises, Nok eventually saves enough to buy a motorbike and embark on a new livelihood zipping through Bangkok traffic as a motorcycle taxi.

Long struggles to raise himself up culminate in joining the massive Redshirt protests which hit the capital ten years ago. A bullet is fired through his skull. He’s left permanently blind.

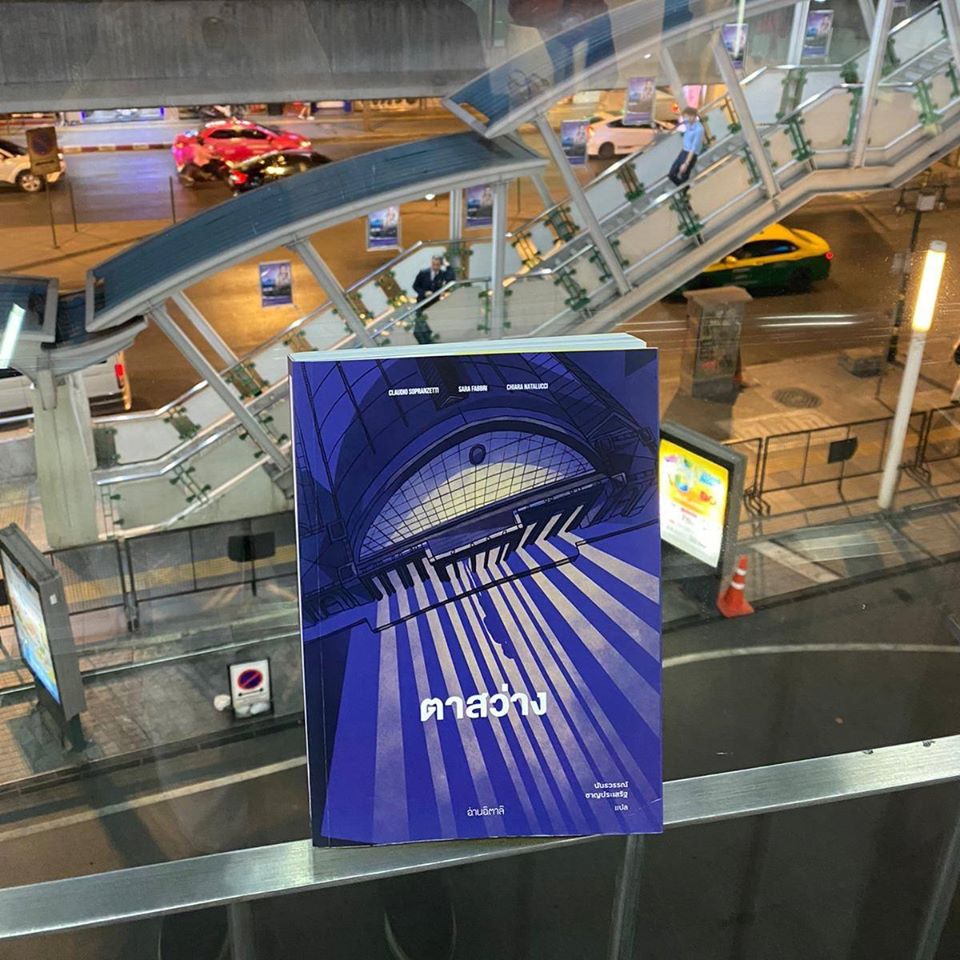

The decades of history that unfold in Ta Sawang, or Awakening, show a throughline that resonates today of people struggling and sacrificing to build a better world despite prospects for justice and democracy that remain, then as now, as dim as ever.

Told in more than 200 hand-drawn pages in a new graphic novel, the story is familiar to many Thais. Though Nok is an invented protagonist, his story is not, as he is a composite character based wholly on real people interviewed by an Italian researcher.

The result is a dramatized account of very true stories that its authors have dedicated to “every victim of political violence, those who live with wounds and those who suffer great losses.”

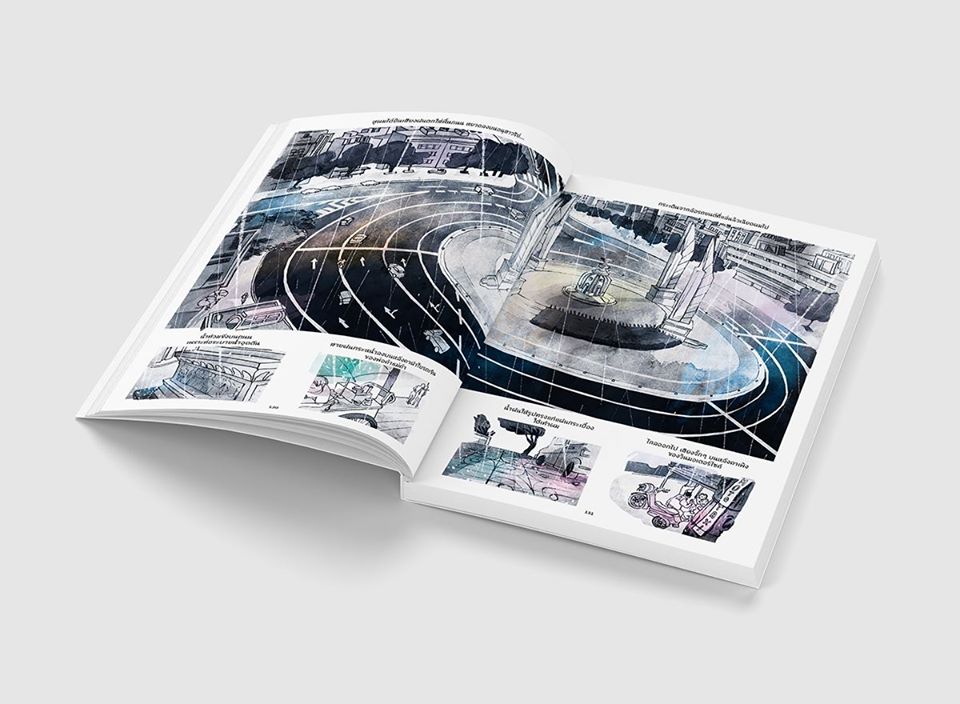

The publication is, if not the first, one of the first graphic novels dealing directly with Thailand’s politics. While it may remind some readers of Persepolis – a graphic memoir circling around a single character during Iran-Iraq war – Ta Sawang jumps between past and present in colored and monochromatic pages reflecting the protagonist’s impairment.

Throughout the title, there are glimpses of self-censorship in the form of sentences deemed “sensitive” masked with bold black lines.

Launched recently at Lit Fest 2020, a book fair held last month at Museum Siam, the graphic novel has been well-received among the progressive set, including a former Future Forward MP, political scientists and writers. It has become the best-selling book at several bookstores.

Though the book’s set in the kingdom, it’s written by a group of Italians whose close study and knowledge of Thai politics rivals most of those born here.

One is Claudio Sopranzetti, a 36-year-old Oxford postdoctoral fellow whose thesis study of Bangkok motorcycle taxis coincided political unrest sweeping the capital in 2010. That thesis eventually became 2017 book Owners of the Map: Motorcycle Taxi Drivers, Mobility, and Politics in Bangkok, which was pulled from one of Bangkok’s largest booksellers without explanation.

I traded messages with Sopranzetti, who’s now teaching at a university in Budapest, about his most recent publication:

Ten years ago, you were researching win motosai as an information network in Bangkok when massive street protests erupted. A couple years ago they were the topic of your book Owners of the Map. That suggests a personal as much as professional interest for you. Why is that?

I arrived in Thailand the first time almost 15 years ago as a tourist but very quickly it was clear to me that traveling the country with my backpack was not enough for me. I started learning Thai and ended up moving stably to Bangkok. In many ways Thailand has become my second home and when your home is in trouble you are naturally driven to try to figure out what is happening. My job is researching and writing, that is what I can do, so I decided to do that.

Are there any graphic novels you and your team look up to? What were the main obstacles in the process?

The graphic novel is not really a development of Owners of the Map, they are very different texts with a very different focus. The first is about the history of Bangkok, of transportation systems and of political protests. The second is a personal history of a small group of people over 30 years as a way to reflect on the collective history of a country.

What connects the two were stories, stories I collected during my research and that, I thought, deserved to be told, especially while many people in Thailand are trying to cancel and mute them. That was the struggle, how do a group of farang tell a “Thai” story? What rights to we have to do that? What attention do we need to have not to transform them into stories without a Thai sensibility? This was the main challenge, putting our egos aside and try to tell the stories we were told, not the one we would like to tell.

While you studied Thai politics and conducted numerous interviews over 10 years, why did you choose to tell Ta Sawang through only one protagonist, Nok?

Nok is not a real person but he is the condensation of a few people whose stories were particularly powerful to me. What we wanted was not to tell the story of Nok but rather to talk about collective experiences. Hopefully you can be a very wealthy Thai or even an expat in Thailand and see some of your experience and feeling in his story.

The book was launched in a quite timely manner, given the current political situation in Thailand, could you share some feedback from your readers?

We were very, very positively surprised about the response. As I was saying before we were very nervous about the reaction of Thai audiences, after all we are telling a Thai story without being Thai, a very personal story in which we are engaging with emotions, experiences of Buddhism, love in the villages, themes I studied and wrote about but never had a first-hand experience. Fortunately the response was fantastic, we are receiving a lot of good feedback and thank you notes and each one means a lot to us. Maybe the most significant comment for us was someone who wrote “thank you for telling us story that we could not tell.”

You haven’t been back in Thailand for some years, why?

I have not, unfortunately. Part of it has been related to my new job, but also from an increasing level of repression against scholars and thinkers, mostly Thai, but also international.

What’s next for your career? Anything Thailand related?

I am now teaching at the Central European University [in Budapest] and continue to write about Thailand but, both for personal and professional reasons, I am now spending more time in Italy, so for a bit I think I will take a break from my work in Thailand. I do have a new project there, a very different one, but I don’t want to spoil anything.

‘Ta Sawang’ is written by Sopranzetti and Chiara Natalucci, illustrated by Sara Fabbri and translated into Thai by Nuntawan Chanprasert. It’s available for sale at most major Bangkok book retailers and online.