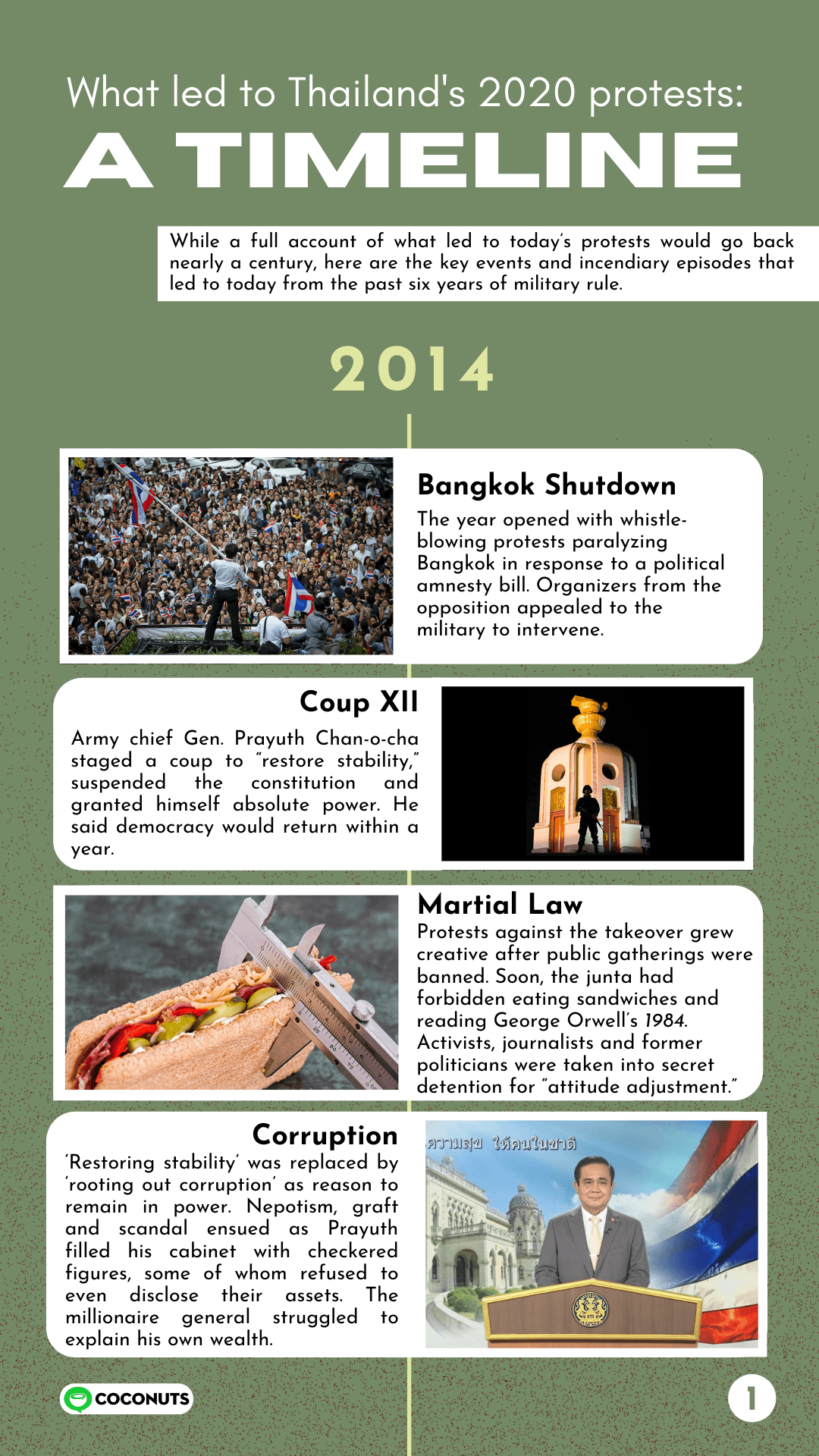

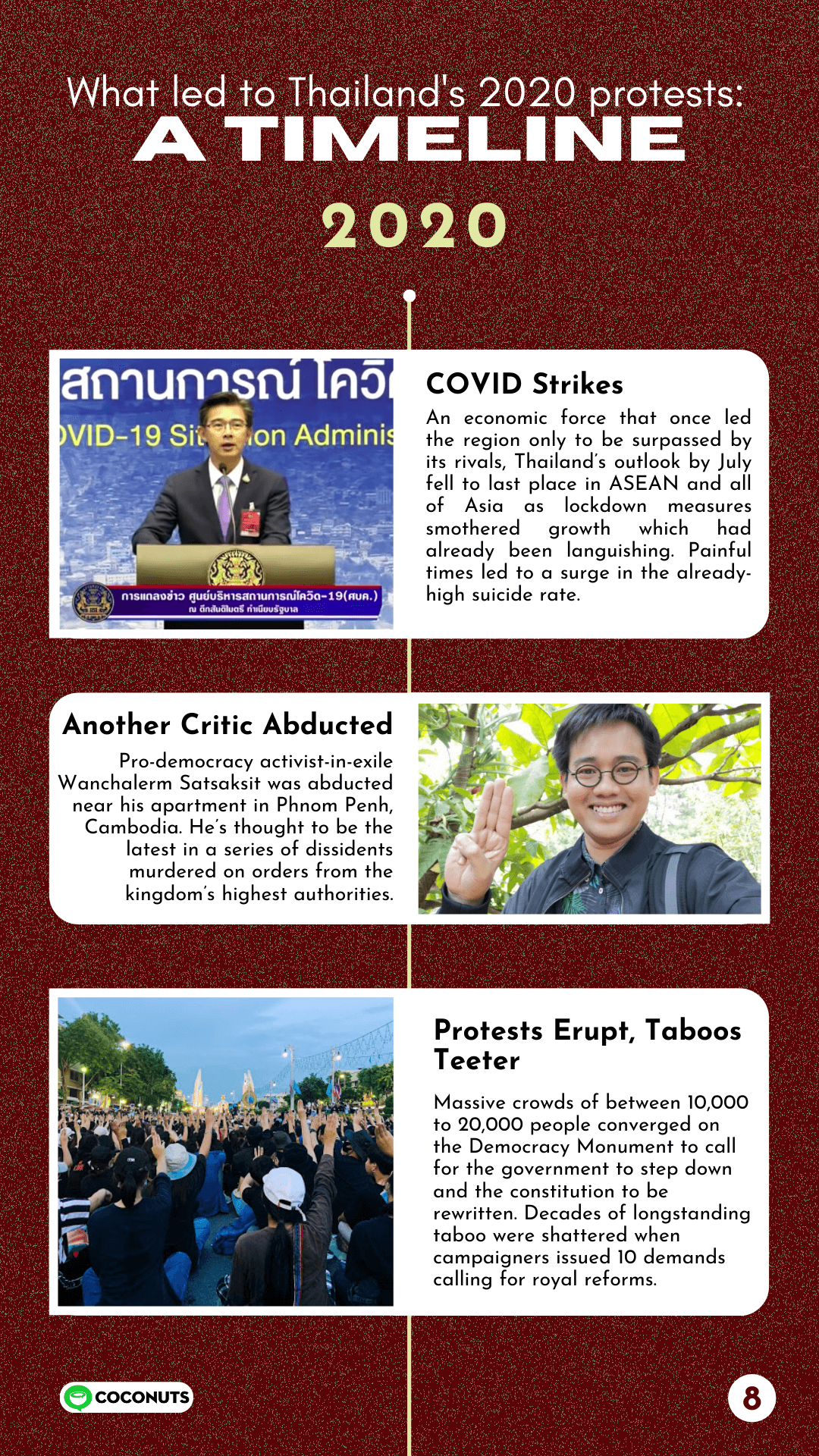

Thousands of youth this weekend will return to historically potent sites in Bangkok where they hope to partially repeat history: Bring down a dictatorship through peaceful protest without becoming victims of state violence.

There’s a cycle of rising protests to dismantle military power and restore self-rule only for it to clamber back in place. 1973. 1976. 1992. Leading the way each time have been students, who have only prevailed after paying a cost measured in young lives.

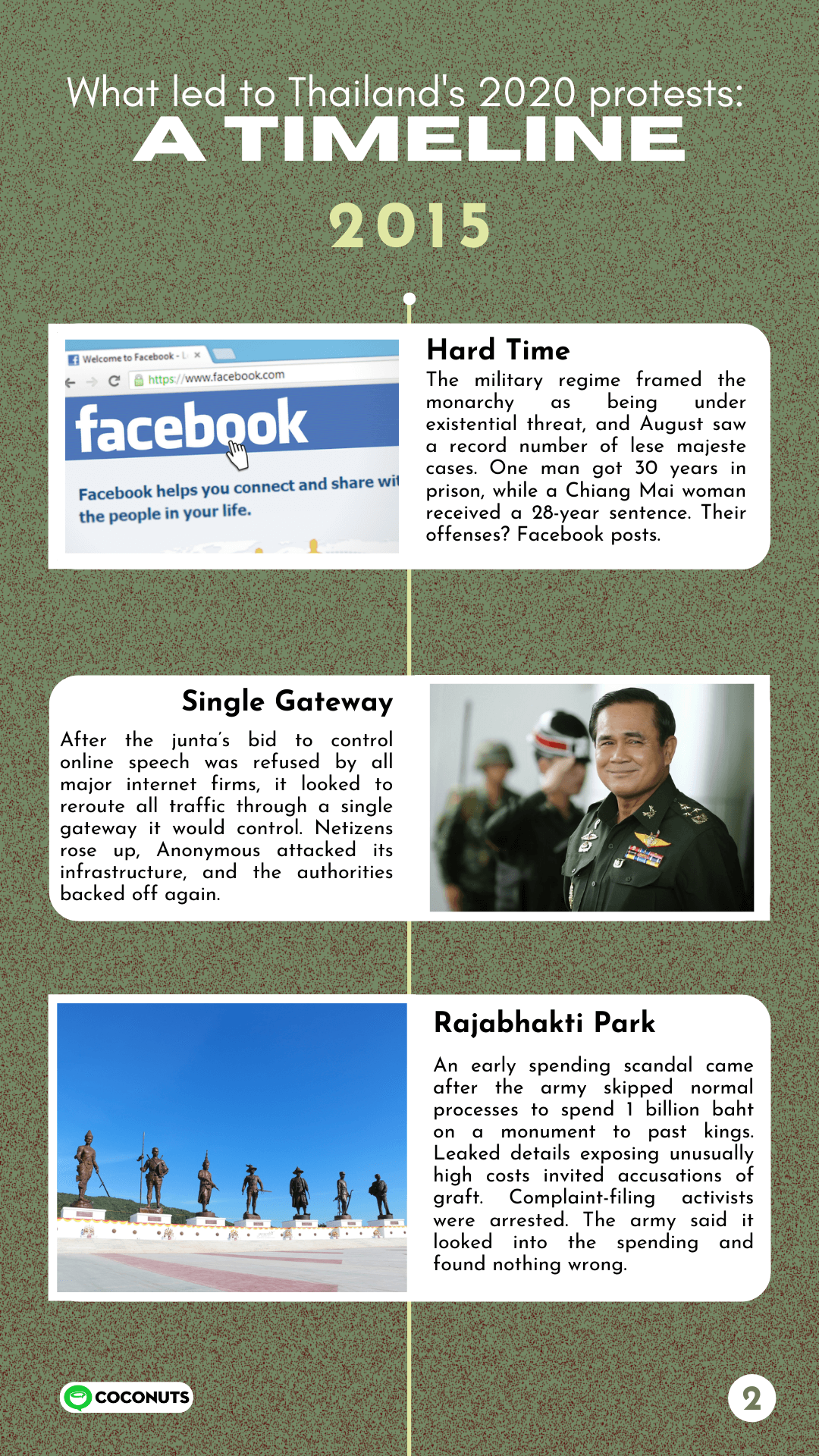

With that backdrop, 2020 finds itself in familiar territory. Over six years after the nation’s 12th coup d’etat, its architects of the National Council for Peace and Order hold onto power after rewriting the rules to maintain their grip under the veneer of civilian rule.

They were seen as mismanaging the economy prior to its pandemic ravaging while spending profligately to better arm themselves and enrich their friends. The baramee, or charismatic authority, that came with vows to smash corruption and drag a polarized nation out of dysfunction has been exhausted.

How did we get from there to here? Why have many of those who ushered the coup in by blowing whistles in the streets nearly seven years ago and applauded a coup turned on military rule? Here are some of the key developments that sank the military-backed government’s credibility and popularity since it seized power.

Graphics: Kanittakarn Paireepinart

May need to zoom on some mobile platforms for interactive version: