This is the second in a series of stories by Coconuts Bangkok about modern day slavery flourishing across borders in Southeast Asia. Read the first or third.

The 40-year-old man calmly sipped iced coffee inside a Bangkok chain cafe in a plain white T-shirt. To anyone else, he would appear just another cafe customer taking a break. They would have no way of knowing that, just a few hours earlier, he had been trying to convince a criminal court room that he was a victim of human trafficking and not a willing criminal.

As we recounted earlier this month, the man, who agreed to speak on condition he only be identified as Nop, was held captive for seven months – December to July – at Cambodian casinos and a hotel where he was forced to work long hours scamming Thais back home. He offered more insights into his ordeal on a recent afternoon after appearing in court.

How did he swindle them? Love. He created fake profiles on dating apps – specifically Tinder and Omi – to find victims, whom he eventually asked to invest in business ventures. Nop said his captors expected him to get several thousand dollars per month – or else he would be beaten or electrocuted by his bosses, which he described as “Chinese gangsters.”

“I cried and cried. I didn’t know when I would be getting out to see my family again,” Nop said.

‘I’m a victim, not a criminal’

Nop, who said he still feared for his life, was among thousands of Thais lured by false employment promises to Cambodia and tricked into virtual slavery.

In the past 12 months, Thailand has repatriated 2,000 citizens from across the border, according to Ramrung Worawat of the Ministry of Social Development and Human Security.

Cambodia has been known as a source of human trafficking victims for years; however, the nation recently become a destination country as online scams exploded during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Chak Sopheap, executive director of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights.

Chinese scammers hold ‘thousands’ of Thais captive in Cambodia: police

“Thousands of people, primarily foreign citizens, are forced to work in precarious conditions after being kidnapped or tricked into accepting jobs in the country,” Sopheap said. “Unfortunately, the Cambodian authorities denied for months that the human trafficking situation was deteriorating as scam compounds were proliferating.”

The U.S. State Department downgraded Cambodia to Tier 3, its lowest grade, in its most recent human trafficking report due to its “lack of significant efforts” to root it out. The report also alleged that Cambodian police and government officials are involved in online scam operations.

“Corruption remains a major issue in the country, as it permeates almost every sector of Cambodia’s public life and all levels of government, including law enforcement and the judiciary,” Sopheap said. “This hampers genuine and efficient government actions and allows gross human rights violations, such as human trafficking, to occur, persist, and spread, at times.”

Ramrung said that the ministry has been working with Thai police led by Gen. Surachet Hakphan to rescue Thais trapped in Cambodia and provide assistance to trafficking victims.

But returning to Thailand on July 29 didn’t end Nop’s trials. Upon his return, he was charged with five crimes including money laundering and participating in transnational organized crime – crimes punishable by years of imprisonment.

While awaiting trial, Nop remains free on a THB100,000 bond – the money he said his mother and aunts borrowed from others. He still does not know how to repay them as he cannot find a job back home in Thailand.

“No one wants to hire me as soon as they see that I am facing criminal charges,” he said. “But what they don’t know is that I’m actually a victim, not a criminal.”

Nop was told he must travel to Bangkok to “report in” at the Criminal Court every 12 days, for eight such appearances. Tuesday is to be the last time.

“It’s to show them that I’m not running away or planning to,” he said.

Nop said he is hopeful that when he goes to court on Tuesday, it will rule that he was a trafficking victim – not a willing participant – but nothing is certain.

“It’s still a 50-50 chance,” Nop said.

Ed note: When Nop appeared Oct. 25 at the Criminal Court for his last of eight mandatory appearances, the court agreed to review his case, and he was given a large electronic monitoring device to wear at all times. He is due to return to court again on Nov. 28.

‘A great opportunity’

A native of Sukhothai, a north-central province of Thailand, Nop previously worked as a building technician in Bangkok. As his elderly mother became ill, he resigned in mid-2019 and relocated back home to take care of her.

That was before the COVID-19 pandemic hit Thailand a few months later, exacerbating the economic crisis. It was in September 2021, that Nop, falling into debt and lacking a stable income, came across a random Facebook post. It advertised a position for a “marketing admin” at a Cambodian casino. The job promised THB20,000 monthly income, or THB30,000 (about US$800) with commission.

“For someone whose education level is below standard, it was a great opportunity,” Nop said.

He accepted the job, and on Dec. 28, 2022, rode a van across the border from Aranyaprathet in Sa Keao province to Poipet in Cambodia.

That’s when the driver warned him about possible danger ahead.

“He warned me, ‘Be careful. You might get scammed.’ That’s when I started to get suspicious,” Nop said.

That suspicion was confirmed as soon as he arrived at the DV Casino, located in the coastal town Sihanoukville. Nop said he was taken to a room on the fourth floor, where the door was immediately locked.

“That’s when I figured out that I had been tricked.”

Demanding to go home, Nop was asked to pay THB120,000 to THB130,000, an amount that was impossible for him or his family to meet.

“I never knew about a single person who actually paid and got released, too,” Nop said.

‘Tell my family if I die’

For more than six months trapped in what he described as “hell,” Nop said he woke up at around 7am before clocking in at around 8am. Apart from lunch and dinner breaks, Nop could not clock out from his “work” until midnight. Then he must head immediately to his bedroom, which he shared with another 10 or so men.

“I couldn’t even get a minute outside. My skin got super pale while I was there,” he said.

Asked what the workplace looked like, Nop said to imagine an “internet cafe.”

“One room has about 40 to 50 people. They work in front of a computer screen for long hours, days and nights.”

Nop was instructed to lure his victims through popular dating apps Tinder and Omi. He was taught by his “Chinese bosses” to create a fake profile, ideally with a photo of a “sexy woman.” Then he would convince his matches – who were all Thai men – to transfer money to him.

“Men are more vulnerable in this case,” Nop said. “Some of them want to act like a sugar daddy and pay for girls to fall in love with them. But in turn, they fall for the scams.”

Unable to meet the threshold set by the scam masterminds, Nop would get beaten, kicked, and shocked with an electric baton. Nop said he even saw his Vietnamese peers splashed with cold water and locked inside a “cold room” where temperatures were set to the lowest.

“I didn’t even know if I would survive from this,” he said. “I asked someone there, ‘Please, tell my family if I die.’”

Nop was later sold to two other scam centers – Jin Cheng casino and Chon Chav International Hotel. The latter was where he reached out to Thai police and the Immanuel Foundation, a Lutheran group that aids trafficked people.

“I had to be very, very careful, though. Because we were monitored all the time, the police could not contact me first. I had to be the one who initiated conversations.”

Nop was rescued by Thai authorities in June. He successfully arrived in Thailand on July 29.

Speak up for others

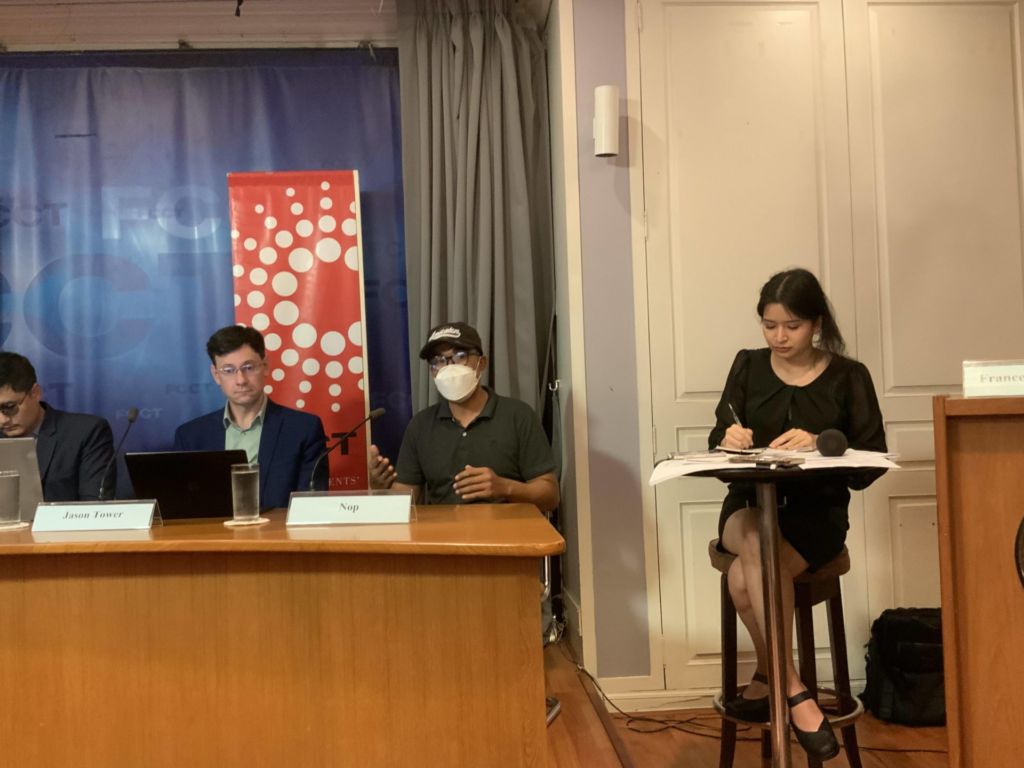

Nop appeared at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club in Bangkok in late September alongside two people who helped rescue him: Gen. Surachet and Jaruwat Jinmonca, cofounder of Immanuel Foundation.

He said he was there to raise awareness about online scams, which have ensnared untold numbers of people, and “expose” the scam gangs.

“I want to project this issue to wider audiences, not only in Thailand or Southeast Asia, but the world,” he said.

Nop said he is now also fighting for other victims who were tricked and forced to run online scams like he was. Every human trafficking victim, he said, should be provided screening tools and fair trials.

“Some people did not have evidence to fight in the court,” Nop said, adding that his mobile phone was seized by the Chinese gangs, therefore he never had photos to prove his experience.

Even though he has not been ruled guilty by the court, Nop said he’s already been judged and stigmatized by Thai society. Victimized twice over – forced into scam slavery and now denied employment because of it – he believes the Thai government needs to provide a post-rescue program of victim services or workforce development programs to help those rescued find employment again.

And it’s not just Thailand that needs to take action, but its neighboring countries where human trafficking is flourishing: Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.

The Cambodian government has recently recognized human trafficking issues, cracking down on online scam compounds and rescuing enslaved workers – efforts that Sopheap of the human rights center said were commendable, but insufficient.

“The Cambodian government must take further concrete steps to investigate online scams and ensuing human trafficking, identify the operators of scam compounds, and bring them to justice as well as provide adequate assistance and protection to the victims,” Sopheap said. “Human rights activists and civil society organizations also play a crucial role in alerting about the existence of such practices and in lobbying Cambodian authorities for increased action.”

Surachet has said that thousands of Thais remain held captive.

Each of those, if rescued, faces the same legal jeopardy upon their return as Nop, who is waiting to find out whether he will reenter society – or captivity anew.

Related

Chinese scammers hold ‘thousands’ of Thais captive in Cambodia: police