It’s 9am and Duanpen Jaengpracham sits patiently at the end of the Ko Tor community pier, where the sea breeze keeps her cool as the day heats up. She’s waiting for her husband and daughter, who have been out fishing since 3am. Duanpen, who is called Khun Pen, is hoping they land a decent catch.

A large, long-tail boat has already come in. The crew, all members of the same family, are working hard to unload. They’re happy, having caught a tonne of Lang Keaw, or sprat, last night: much more than the average haul of 200 kilograms to 300 kilograms. It will fetch only THB6-7 per kilogram. Thus, large hauls are a big deal.

Khun Pen, 50, usually joins her family on the boat but has stayed behind to tell Coconuts how her story intertwines with that of the sea, an ever-diminishing bounty blamed not only on climate change but also practices closer to home – industrial pollution, poorly designed nets, harmful abandoned gear – and innovative attempts to address them.

Those problems weigh on hope that her husband and daughter will return loaded with crab this morning.

“I used to set my nets up and light a cigarette. Once I’d smoked it, the net would be full of crabs. Now, it’s more likely I’d finish a whole pack before I get enough,” she said chuckling, before her smile faded. “We’d get 300 (kilograms) to 400 kilograms of crab per day for eight months of the year. We had too many to sell and sometimes had to throw them out. Today, crab can only be found for a month each year. I remember not seeing them for three years. Now, an average catch is only 10 kilos.”

Khun Pen would know. Fishing runs in the family. Her father was a fisher; she married a fisher, and all of her three daughters help out at sea. Having fished off the coast of Samut Prakan for 30 years, her memories of more abundant days of the past are vivid.

“Just 10 years ago, I would see dolphins, sharks and whales when at sea,” she said. “The dolphins would swim around and under my boat. I’m sure they jumped when I told them. Now we have to travel far out for a chance to see them.”

Safety net

A member of the board representing Samut Prakan’s artisanal fishing communities, Khun Pen described how climate change has made coastal waters warmer, causing once-common mackerel to disappear as the water’s now too warm for them to lay their eggs.

“We have to go far to catch mackerel,” she said. “I don’t bother going for them anymore. Overall, stocks of all species have fallen and fishing families with many mouths to feed are facing problems.” Climate change is just one of many reasons this has happened.

“I think it’s partly caused by nearby fabric factories which release chemicals into the sea,” she added, “and there’s illegal fishing. People outside the community use illegal Ai Ngo nets which catch all species indiscriminately.”

Ai Ngo nets do not have specially designed escape routes for juvenile fish or non-target species to break free. When fish are caught too young, they cannot be sold and are thrown away. This means they don’t get a chance to reproduce, causing fish stocks to plummet.

Khun Pen has reported the problem to the authorities and sometimes they come to remove the nets, which they find unsupervised and laid out on the seabed. It’s hard to catch the culprits because there is no way of identifying who owns the nets.

She says there are desperate people who use these unsustainable fishing methods to earn cash to feed drug habits. When officials come to investigate, she has seen them shout and throw stones at them.

Asked about plastic pollution, she does not think it’s a big factor in fishing decline, though, it still creates frustrating problems.

“I pulled my net in to discover plastic bags and nothing else. Water filled plastic bottles and bags snag and tear our nets when we pull them in,” she said. “Discarded bags and old clothes can get tangled in the boat’s propellers, costing both time and money.”

‘Ghost gear’

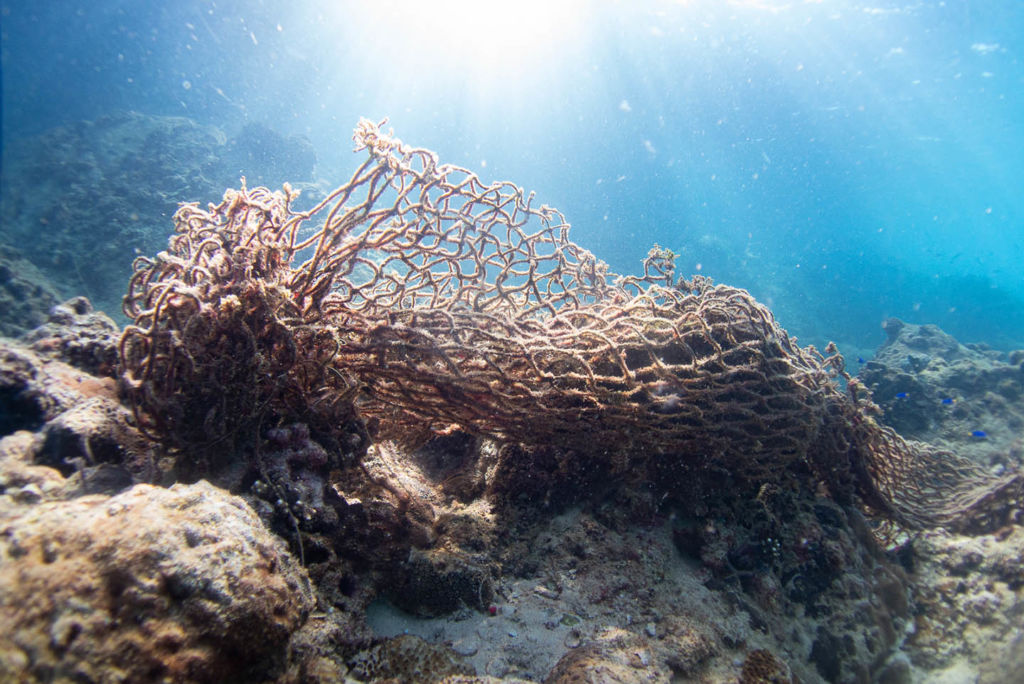

Another issue facing fisherfolk and likely contributing to falling yields surrounds so-called ghost gear. This is abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing equipment that ends up in the oceans without any control.

“It’s a deadly form of marine plastic pollution,” said Salisa Traipipitsiriwat of the Environmental Justice Foundation. Traipiptsiriwat coordinates the foundation’s Net Free Seas project, which is working to overcome the problem.

“Once leaked into the ocean, old fishing equipment continues to do what it was designed for: catching or entangling whatever it comes into contact with,” she added.

Whales, turtles, seabirds and all kinds of marine species can become trapped as nets, ropes and other unwanted fishing tackle drift aimlessly in the water or sink to the seabed.

“The Environmental Justice Foundation estimates that a small fishing boat will generate a minimum of 5 kilograms of waste fishing net per month. There are over 60,000 commercial and artisanal fishing vessels in Thailand. This means that monthly, at least 300,000 kilograms of plastic could be leaking into the ocean,” Traipipitsiriwat said.

Last year, divers removed nets covering 2,750 square meters of coral reef near Koh Losin off the coast of southern Pattani province. When nets settle on a reef, the waves and currents move them around, snagging and breaking off the delicate parts of the coral. Eventually, the coral and other species they support die off.

Detailed data about the exact impact of the ghost gear in Thai waters is yet to be gathered. Rahul Mehrotra, a post-doctoral researcher at Chulalongkorn University and program director at the gulf-based Aow Thai Marine Ecology Center said they have little idea how bad it is:

“Both South East Asia and Thailand are big voids of information on the extent of the problem compared to other regions of the world. However, it’s suspected the impact is extensive because of the vast scale of the fishing industry and the minimal resources available to manage or study the associated problems.”

Research shows ghost gear isn’t just a threat to coral and reef fish, but also sea snails and other seafloor critters.

“They often have jagged, pointy shells which become entangled in nets and die in large numbers,” Mehrotra said. This is important as many larger marine creatures rely on them for food.

The data reveal that the crabs Khun Pen hopes to land are also impacted by ghost gear. Their claws, pincers, and legs can easily become entwined in abandoned nets, making it impossible for them to move around to feed or reproduce.

Khun Pen said that disposing of the old fishing nets has been a long-term problem for her community. The local municipality provided a bank of garbage disposal bins but did not arrange a collection service.

“We were forced to carry the trash some 300 meters away from our bins to and leave it outside the local temple for the authorities to pick up. But it was impossible to motivate people to carry the waste to the collection point, so it would just pile up,” she said.

Fishers ended up either dumping their worn-out nets in the khlong or burning them, causing toxic smoke to be released into the air.

Reason for hope

But the net’s material value may be providing a solution, as she has found working with Net Free Seas.

“The Net Free Seas project aims to connect small-scale fishing communities with recyclers, creating a supply chain that turns discarded fishing nets into homeware products for sale to consumers,” the Environmental Justice Foundaiton’s Traipipitsiriwat said.

For Khun Pen, it’s also an opportunity for herself and her peers to generate some extra income.

“I pay people 10 baht per kilogram for old fishing nets and help clean and prepare them for recycling. I then sell them on to the recycling company for 13 baht per kilo,” she said.

A company called Cirplas Tech turns the fishing nets – along with plastic bottles, coffee cup lids, and other used plastic items – into pellets to be used again.

“The nets are particularly hard to recycle as they must be washed many times before they can be processed into the pellets needed,” Cirplas Tech owner Thosaphol Suppametheekulwat told Coconuts.

Thosaphol also owns Qualy Design, which creates a range of lifestyle products manufactured from the plastic pellets. Popular merchandise includes fridge magnets, plant pots, and coasters, as well as a push stick to avoid contact with public buttons during the pandemic.

Many products have an ocean theme. “Using material recycled from fishing nets is a great way to connect concerned customers to a solution to marine plastic pollution,” Thosaphol said.

Net Free Seas operates in more than 100 fishing communities nationwide. Since its launch in 2020, it says it has recovered 44 tonnes of material from Thai waters and plans to replicate its success in Indonesia and Ghana.

“It’s good to sell the old nets. I don’t want them to end up back in the ocean because of the damage they could cause,” Khun Pen said.

But she’s well aware of the many other threats to the ocean supporting her family’s way of life, which won’t be tackled until Thailand moves toward better-managed and more sustainable fishing practices that conserve the species and environment on which her livelihood and everyone’s food security depends.

Related

Rescuers struggle to save unemployed Thai elephants from worse than exploitation

Unsung trash heroes save Bangkok from choking on its own waste

8 life hacks for greener Bangkok living now – and after the pandemic

Did Thailand’s plastic bag ban solve our problem?

A walk on the wild side: Foraging for Thailand’s forgotten edible plants

Before it spawns the next pandemic, should Thailand stamp out the wildlife trade?