A leering ghoulish figure extends its elongated tongue toward a bare-breasted woman in bed struggling to cover herself with the sheets. A demonic head trailing viscera of ragged, bloody intestines floats menacingly over terrified villagers.

Forty years ago, Tode Kosumphisai, the artist responsible for these images, was in top form, cranking out wildly popular comics sold everywhere. Their graphic violence and nudity served a favorite form of escapism during the political upheaval of the 1970s. Then came moral panic in the ’90s, and such work became demonized as vulgar and juvenile.

Decades later, Tode still does not see it that way.

“It’s a selling point. You need to see some tits!” the 66-year-old illustrator said recently at an exhibition on the history of comics. “They would tell me ‘Hey Tode, make it more chesty! Why would anyone buy anything with skinny ladies?’ All the ladies, whether the lead or the evil ones, must have tits!”

While some may know the name Tode Kosumphisai, many adults will recognize his gruesome and sexually provocative depictions of Thai folklore and horror. He is one of the last surviving artists of a bygone era of comics that were widely read but today are in danger of being forgotten, save for a few people attempting to celebrate and preserve them.

Although Tode did not create the genre, he remains a favorite from the long-faded pages of 1-baht comic books, or katun lem la baht, that peaked in the 1980s.

While Tode – real name Sungsak Supromphant – accepts comics’ fall from the mainstream, he recently returned from retirement to pick up his brush and draw fantastic things inspired by news stories, pop culture, horror movies, and more.

He was one of many once fueling a massive industry. Dozens of artists made their living crafting stories from the same pool of ghouls that make up Thailand’s vast roster of demons and ghosts – and regularly cross over onto the big screen. Creatures like Krasue, a fiendish favorite across Southeast Asia recognized for her floating, disembodied head trailing ribbons of raw, bloody organs in fruit-punch red.

Coconuts Bangkok’s Thai Ghost Guide

Tode drew Krasue and other monsters in comics that usually ran 16 pages and cost THB1. They featured striking horror designs in which every centimeter was packed with menacing phantoms – and a lot of naked ladies.

Even though popular Thai culture at the time was more comfortable with depictions of sexuality, Tode’s work was too much for some. Like the time he got a letter from the Education Ministry.

“It said that this type of literature was considered low-class,” Tode said. “They looked at my work as something that people shouldn’t pay much attention. But they also warned me not to put in so much nudity.”

And as the impression grew that such comics catered to the low-class and adolescents, their popularity declined. By the late ‘80s, Thai publishing houses couldn’t compete with Japanese comics (Tode says they pushed boundaries even further), and readers fled as the content became trashier one-offs without memorable characters, and prices rose to 5, then 15, then 25, and even 45 baht.

As the form became undone by a loss of quality and negative opinion, it’s little surprise that few saw any value in preserving or archiving it.

‘Destroyed by time’

Today, little remains of the comics that millions of eyes pored over for decades. Few serious efforts to save or preserve them meant much of that work was lost without a trace. And not just the 1-baht pulp comics, but decades of more serious cartooning that preceded them.

“There is not much research in English, and in Thai there are about five books that talk about Thai comics history that aren’t written by scholars but aficionados,” said Chulalongkorn University lecturer Nicolas Verstappen. “For instance, there’s not much research about dates, only decades and names. There is no context provided, which to me is very important.”

Decades later, Verstappen has tasked himself with chronicling Thai comics’ storied history.

At the BKK Comics Art Festival that just concluded downtown at the Bangkok Art & Culture Centre, which Verstappen helped organize along with Indian artist Sketchman Boris, a section was reserved for Tode’s colorful and lurid works alongside those of contemporary artists such as Art Jeeno, Sa-ard, and Jod 8riew. At an accompanying exhibition, works going back over a century were displayed.

Works by Apichat Rodwathnakul

The exhibition and festival that gathered Thai comics fans followed on Verstappen’s 2021 book The Art of Thai Comics.

In the book, Verstappen gave in-depth history and examples of comics dating as far back as the early 1900s. While the hefty book covered a large portion of Thai comics, he says a lot is missing – and may never be found.

“Most people do not think it’s a worthwhile medium,” Verstappen said. “And so they’ve been left in boxes lost in monsoons and were destroyed by time.”

His search has led him to find comics at public libraries, bookstores, and private collections. A collection of works by famed comics artist Jamnong Rodari was found in an attic.

“Jamnong Rodari’s content came from the 1930s,” he said. “There’s still many comics in the 1920s that are still missing, almost a century ago.”

The cartoons of that time, he added, were inspired by satirical British cartoons and were serious in tone. They were commentary expressing political opinions and were often found in the newspapers of the time.

‘A very serious medium’

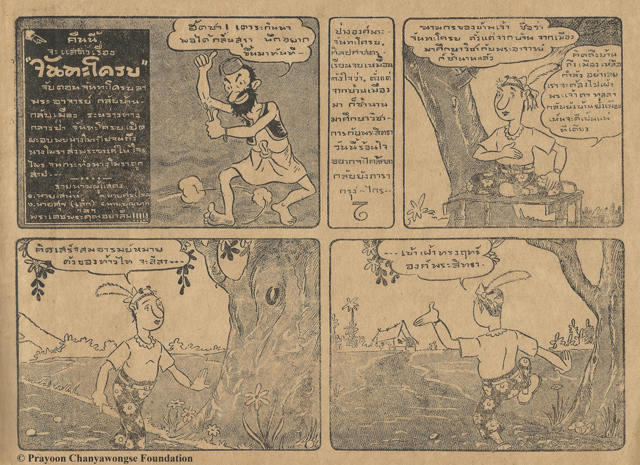

Most of what’s been written about Thai comics in the past is too insidery to have been noticed by the wider world, Verstappen noted. They assume a familiarity with cultural references to things such as likay theater – akin to the West’s Vaudeville – that was a common device in the late 1930s comics of Prayoon Chanyawongse.

Cultural context is vital in understanding genres like the katun lem la baht, which was steeped in horror stories based on folklore.

“The elites were making the comics; they were a very serious medium,” Verstappen said.

He said that all changed in the ‘70s when the middle class began making comics that deviated from the sophisticated styles of the past.

“That was when comics took on the impression of being childish, and thrown away,” he added. “They were never kept in museums and libraries.”

Drawn together again

Peataya “Peat” Werasakwong, cofounder of independent comics publishing company Kai3 and brother of famed illustrator Sa-ard, noted that there was enough demand for comics to remain commercially viable until the late 2000s.

“Social media and Netflix stole reading time from comic books,” the 37-year-old publisher said. “There was a downward slope from that peak. People weren’t buying comics as much, but artists were still drawing, not because of a trend, but because they love it.”

Today, Peat has a brighter outlook. The new generation has sparked a wave of independent artists who have set aside paper to publish the ever-growing number of graphic novels and webcomics.

And while they are more niche than during their heyday, the passions run just as strong.

Asked if comics will ever be taken seriously again, Peat said attitudes change with each generation.

“It’s hard to break those stereotypes, but the people who grew up on comics will be able to select what kind of content they want to consume,” he said. “And in turn, when they grow up there will be less of that old way of thinking. There will be more interest in comics.”

The grassroots nature makes for a more democratic form today.

“Artists know what the readers want to read,” he added. “There’s no longer a need for an editor who decides what can be published. It’s all direct.”

Through all of that, Tode has kept drawing.

Not long after he retired in 2018 because it had gotten too difficult to find work, he met avid ‘80s comics collector and admirer Arttakrit Jeenmahant on a TV set.

“So I went to his house, and he told me he wanted to draw comics, but there wasn’t any place to print,” Arttakrit said. “He hadn’t been drawing anything for two years. So I asked Khun Tode to draw some new comics for me.”

A few years on, Tode’s ghastly work continues. With Arttakrit as his partner, he is not only making new illustrations but minting them for sale on NFT marketplace OpenSea.

Tode, who’s technology illiterate, says that while he doesn’t even know what an NFT is, he’s glad he’s able to do what he loves.