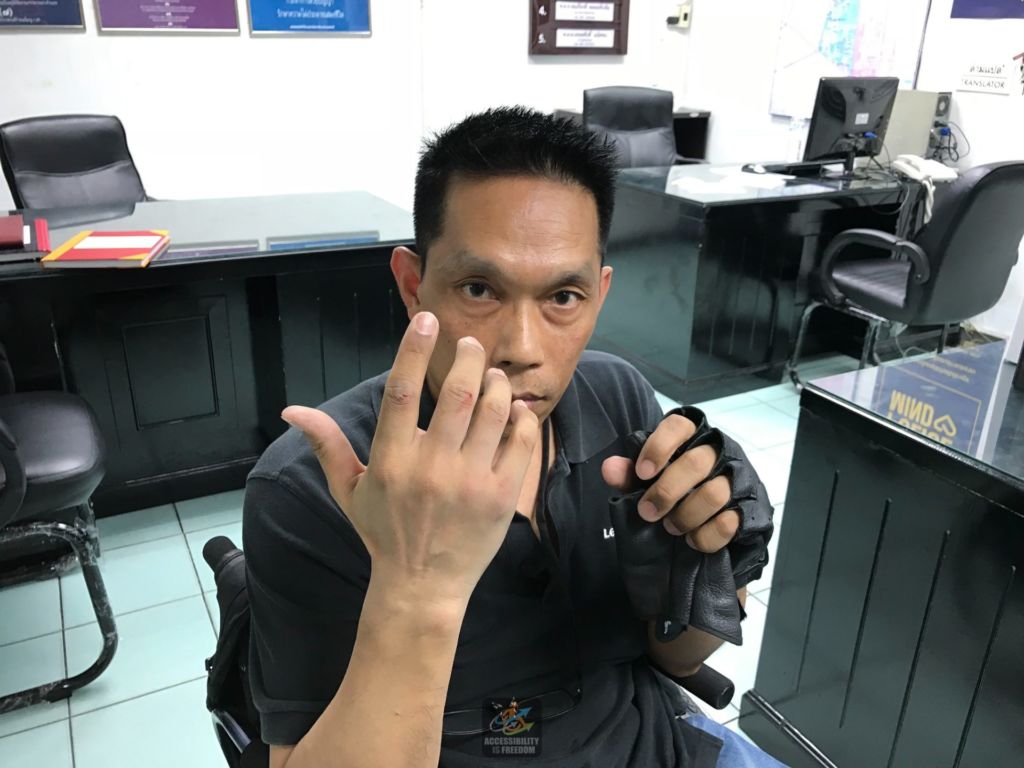

The man in his 50s wears his hair in a spiky crew cut and dresses in monochrome: black polo shirt, gray gym trousers, and dark sneakers perched on a footrest above a sign reading, “Equal.” Hands covered in glossy dark gloves deftly push the wheels by which he navigates Bangkok, but something has gotten in the way. Potholes small and large fill the way for the next 100 meters. He slowly weaves left and right to dodge each of them.

“Every time I leave the house, it feels as if I’m going into a warzone,” he said.

Those are the moments that motivate and enrage Manit “Saba” Intharapim, an advocate and fierce fighter for an accessible city. Eight years after he founded Accessibility is Freedom, he’s gone from an “IT guy” in a wheelchair to a respected figure and familiar face within and without the community of people with disabilities.

Over the years of nudging, pushing, and literally punching for basic consideration from urban and transportation planners for whom inclusivity is an afterthought, Manit’s built extensive connections and now regularly deals with everyone from politicians and architects to mall executives and transport guards.

Manit, 55, dreams of a Bangkok where all citizens are ensured equal access to public spaces, regardless of their physical capabilities. Asked which city he aspires to emulate, he replies without hesitation: “Tokyo.”

On a recent afternoon, he pointed out a wheelchair ramp at Siamscape, a mixed-used building that recently opened in the Siam Square area.

“Look at this slope. It’s too steep for most people on wheelchairs to ascend,” Manit said.

To prove his point, he stretched a tape measure across the ramp’s length.

“This is illegal, but there is no punishment for the violators,” he said, referring to the Accessibility Act, which mandates that wheelchair ramps have a 1:12 slope ratio (1M of elevation for every corresponding 12 meters of length, for example).

The list of obstacles goes on and on. Too-narrow sidewalks, broken up pavements, lack of ramps, signposts planted in the middle of pathways. During trips from points A to B, Manit finds himself stuck repeatedly.

Just on a recent Sunday, Manit found himself stranded in front of Benjakitti Park – a city project otherwise hailed for its environmentally breakthrough design. But he couldn’t get in.

Unable to descend from a rampless curb, he had to ask a high school student for help backing him down into the street.

“In a good city, helping out a person with disability should not even happen or should be as little as possible,” Manit said. “In the end, everyone must be able to commute without any limitation.”

“This is the kind of environment that imprisons a person with disabilities and forces them to be disabled forever. Plus, they will continue to think of themselves as an incapable person,” he continued.

Disabled, accomplished

Native to the northeastern province of Nong Bua Lamphu, Manit was born with polio. His left leg was smaller and weaker than the other. But that didn’t stop him from living his life. Manit moved south from his hometown to Pattaya where he attended a school for people with special needs.

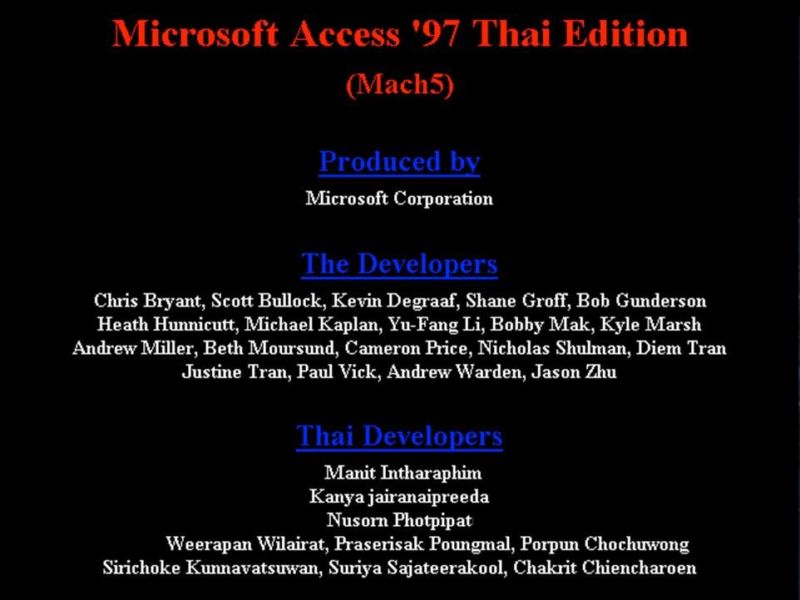

After graduating, he relocated to Bangkok to pursue his dream as a programmer. One of his proudest achievements was developing the Thai edition of Microsoft Office 97. His name tops the list of its Thai development team.

“It shows people with disabilities have potential that’s not different from ordinary people,” Manit said.

Manit’s life turned upside down, however, when he was 24. Working days and nights with few hours of sleep, he dozed off on a motorcycle. The accident put Manit in a hospital bed for nearly a year. Then the doctor told him that he would be paralyzed from his waist down. He has relied on a wheelchair since.

Yet, Manit has lived his life as if nothing had changed.

“I never think of myself as less human than other people. To me, I’m a normal person, not a society’s misfit,” he said.

A meeting after another with Manit, one would be reminded not only the core of his activism but the nature of the world that is change and uncertainty. Manit stresses that his fight for people with disabilities, who are often overlooked by the society, is in fact relatable to everyone.

“Our bodies change all the time. So this is not only an issue for people with disabilities, but it’s everyone’s,” Manit said.

‘Done waiting’

Four years ago, Manit was at BTS Asoke. As a person with a disability, he was entitled to free rides on public transit. But then a security guard told him he must sign a document to “record disabled passengers’ commute.”

Manit refused. He felt it impinged on his rights and privacy. So he went to the ticket booth to just pay the fare. That’s when he spotted an elevator going up to the platform. The door was locked.

Manit waited and waited for a guard to let him in, but no one came. Finally, all the frustrations and slights boiled over. He pulled back his gloved fist and drove it into the elevator door, breaking the glass.

“I was done waiting, so I threw the punch,” he said of the incident which earned him the nickname “elevator-punching man” in newspapers.

Manit’s anger sets him apart from activists who patiently wait for the change they seek. He has a temper and provokes fights – publicly shaming drivers for parking in handicapped spots on social media is one of his pastimes – that sometimes court controversy – and legal trouble.

He’s notched big wins – helping win a landmark case forcing City Hall to add lifts to all BTS stations – only to meet new setbacks – the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration dragged its feet for years on the court-ordered upgrades.

Since Manit punched the elevator four years ago – indeed throughout his nearly decade of activism – he admits that progress toward equality has been minimal. As was the case with the unenforced court order, Thailand’s famously feeble law enforcement plays a role.

The power of shame

When he’s free from working as an IT consultant, Manit goes on regular “missions” to “review” public spaces. This year alone that has included a controversial canal park project, the massive Benjakitti Forest Park, the new Bang Sue Grand Station transit hub, and automated Gold Line expansion.

Apart from his tape measure, a 360-degree camera and tripod are always with Manit to capture all the angles of the places he inspects. Later, the images are posted online along with Manit’s reviews detailing the good and bad of his survey.

“As I was on my way to the park, the sidewalks were in bad condition. At some point, I had to descend to the road. It was also inconvenient to get through the entrance,” Manit wrote about his January visit to Benjakitti Park.

He notes features that are necessary for those with other disabilities, such as those without sight.

“The tactile guide pathways were not yet installed,” he added. “These are things that need to be addressed urgently.”

While most of Manit’s posts commend or criticize designers and planners to raise awareness of user-friendly and inclusive designs, his confrontational style – going after private motorists who steal scant handicapped parking spaces – has made him enemies. And, at present, a defamation lawsuit.

Back in August 2020, Manit posted a photo of a Toyota Hilux Revo Prerunner truck he said was parked illegally at Tesco Lotus Chaeng Wattana. “This car’s driver violates disabled people’s rights and is parked illegally,” Manit wrote on Accessibility is Freedom.

Bangkok disability activist faces jail over handicapped parking space

While Manit didn’t name – or even know – the driver at the time, he did not blur the car’s license plate in his photo. That led the driver to sue Manit, saying his social media post attracted comments that “humiliated” and “denigrated” him.

The case was still ongoing as of publication of this story. Manit said he was fighting the case and, as much as he wants to “take a break” for a month or two in Japan, he has to remain for the trial – something he said is bigger than himself.

“I fought this case not just because it is personal, but for everyone with disabilities,” he said.

‘Future of the City’

With the city’s gubernatorial election just around the corner, candidates have campaigned fiercely and made many promises. Making the city more accessible to all has been among them.

At a May 9 debate held at the Iconsiam shopping mall, Manit fired a question that received cheers from his peers. It was about the hard-fought 2015 Supreme Court ruling that BTS lifts must be constructed.

“City Hall was ordered to install elevators at 23 BTS stations within one year, but it’s been seven years and 168 days, and that’s not done,” Manit spoke into the microphone. “What will the next governor do to get this done as quickly as possible?”

Bangkok scrambles to install elevators for disabled at all BTS stations

After seven years and counting, most stations – 18 of 23 – still do not have elevators connected to the ground level. None has accessible toilets or tactile paving. Manit collects and maintains real-time data online.

The debate was attended by marquee candidates including former transport minister Chadchart Sittipunt, Wiroj Lakkhana-adisorn of the progressive Move Forward Party, former fighter pilot Sgn. Ldr. Sita Divariand, and former deputy governor Sakoltee Phattiyakulwith. Missing from the stage was incumbent Gov. Aswin Kwanmuang, who blamed his last-minute absence on being “stuck at work.”

While some audience members wore T-shirts or wielded signs and even tote bags declaring which candidate they’re rooting for, Manit wore a plain white shirt and dark-colored slacks. He kept his mouth shut about whom he would vote for. Reserved yet succinctly, however, he said the next governor won’t have an easy job.

“No matter who the next governor is, he or she must take into account all groups of people and lead the city into becoming truly accessible,” Manit said. “We have long-standing problems, and we can’t wait any longer.”

As Manit advocates and connects with the city’s decision-makers, he has become aware that he must cultivate ties with the younger generation. That’s meant giving lectures to school and university students on disability rights. That education continues outside the classroom, as well.

When road safety became the top national topic after a doctor was killed in the middle of a crosswalk, Manit invited a group of Chulalongkorn University students to inspect road safety on their campus and around the nearby Siam Square shopping area popular with students. The group included high-profile student activist Netiwit Chotiphatphaisal, who was deposed as student president for his human rights campaigns.

Bangkok’s Mean Streets: Any hope for actual, lasting change?

To learn best is from reality. Some students sat in a wheelchair while others wore blindfolds to navigate roads with a cane. The students recorded each challenge they spotted – from a flat Braille restroom sign and too-steep wheelchair ramp into a building. They said they would submit a letter to the university to fix the issues.

The event, now dubbed “Chula Walk,” will be held regularly, Manit said.

“New changes will be made by these young people, and this is the reason why I cannot ignore them,” Manit said. “They are the future of the city.”

Related

Bangkok’s Mean Streets: Any hope for actual, lasting change?

Bangkok disability activist faces jail over handicapped parking space

Inaccessible: Disability activist risks life to reach Bangkok’s new canal park

FAIL: Wheelchair ramp at new skytrain station leads commuters straight into roadside ditch (Photos)

Bangkok scrambles to install elevators for disabled at all BTS stations

Disabled activist confronts woman using handicapped parking (Video)