Early in March, Thai photographer Jutharat “Poupay” Pinyodoonyachet made waves when Thais found out she was shooting the 95th Academy Awards for the New York Times.

“Dream until it’s reality. I’M HERE AT THE OSCARS!!!,” the photographer proclaimed in a caption next to a selfie taken earlier this month at the annual awards ceremony.

The 30-year-old freelancer moved to New York in late 2019 after becoming fed up with the labor exploitation of Thailand’s movie industry.

‘Dream until it’s reality’: Thai photographer shares Oscar achievement

We talked to Poupay about the “beauty privilege” that conflates talent with looks, and the cultural forces that suppress Thailand’s creative industries.

How was your Oscars experience?

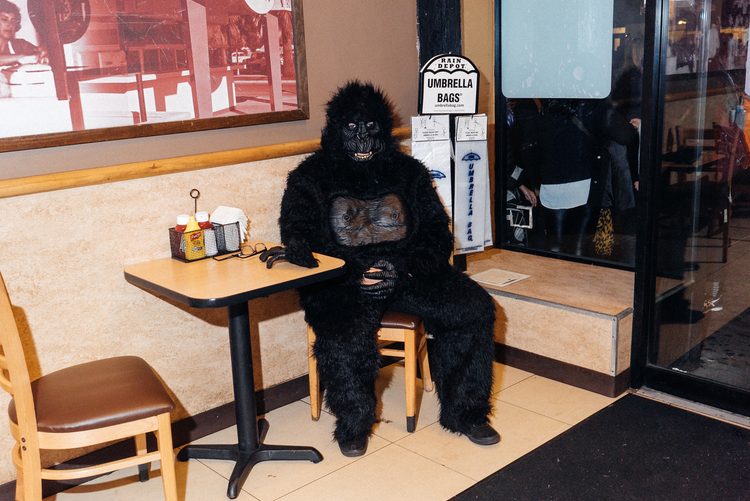

I was very excited. The New York Times sent three photographers and I was assigned to be at the red carpet. I’ve been freelancing for the New York Times for the past two and a half years, shooting arts and fashion—and this was a big event related to both—so they sent me. Next time, I would love to do other spots [at the event] as my photography style is usually very spontaneous and candid, or party moments full of energetic, positive and fun vibes.

Why did you move to New York?

I first came to New York for a study course. After I finished, I went back to Thailand and had friends in the industry who fed me work. I was a still photographer for a film production company and I would work 16 hours a day. Everyone thought that, or even 24 hours a day, was normal. People would tell me, “Yeah, it’s like that.”

The last straw was when I left my home at 5am for a 6am call and ended up getting back home at 7am the following day. I sat on my bed and cried. They didn’t see my worth or even value my life as a production staff at all. The pay was seriously not worth it, or worth it for my mental health to be going through this. I didn’t think this culture was going to change anytime soon, or see how I would be able to change it.

I decided I would go back and give New York another try via the O-1 artist visa — where you have to submit your work portfolio for consideration — and I’d be able to work freelance legally.

How did you get started with the New York Times?

COVID-19 hit almost right after I moved so I was mostly inside. Then there was the George Floyd protests, and it was a very historical moment. It was during a time when you couldn’t even dine next to each other in restaurants but people were out there, fighting for justice while wearing masks, so I went out and took some shots. I submitted the photo set to the New York Times together with another COVID-focused set that was about people living with wearing masks instead of the usual angles of grief and isolation. They said they would keep in touch and my first assignment came three months later. I shot gift shops in Time Square without the liveliness of tourists.

What are the obstacles to being a creative in Thailand?

To be a working female photographer in such a male-dominated industry in Thailand is really hard. There’s a stereotypical image that it’s men who do this job and it’s hard to break through that. Then there’s also a beauty privilege element. If you want to “make it” in Thailand, you would have to fit with the beauty standards here in order for brands to want to sponsor you to use their gear or be a brand ambassador. You could be a total nobody but if you match Thai beauty standards, you’d get a gig and the media would pick it up and write about you as “the famous photographer” even if you had zero experience but looked pretty holding a camera. While in New York, the experience and jobs I get are all about skills. I can grow my career without the need for connections or the influence of the beauty privilege.

On top of that, most of the big commercial recognition platforms in Thailand are very outdated. For example, the categories for competitions always seem to revolve around “being a good-hearted Thai” or “having good morals.” That means your work needs to be very conservative—like shots of temples—in order to be recognized. Art should create discussion and be thought-provoking, but can we really do that in Thailand? With the nation so scared of controversy, how can true art be created?

That’s why I’m not coming back to Thailand. Here in New York, I know that my hard work will be reciprocated fairly without having to worry about male privilege or leveraging connections. My skills are what’s appreciated.

What do you think Thailand needs to do?

There are many arts grants that you can apply for in New York — from both the government and private sector. Even if your work is only 20% done you can often submit it as part of a grant proposal. There are also artist residency programs at galleries, without topic requirements. On top of financial support, getting these grants will help get you involved in the industry and with communities that will support you.

How do you feel when someone says “art is a privilege”?

It shouldn’t be thought of that way because art should make us question all the things around us and be accessible to everyone. The people in power need to make sure that we have art in more public spaces.

Any advice for people trying to make it in the art world?

Well, you first have to ask yourself where you want to make it. If that place is Thailand, I don’t think success has much to do with results, but rather connections and the decisions of people with power and money. If you want to make it in other countries, you have to think like a world citizen and think about topics outside of just “being a good-hearted Thai” or “having good morals.” In Thailand, the industry is often monopolized by people who have power and funds, which means the work here still can’t reach the same level of diversity as the international scene.

To see more of Poupay’s work, visit her Instagram.

Related

‘Dream until it’s reality’: Thai photographer shares Oscar achievement