This is the first in a series of stories by Coconuts Bangkok about modern day slavery flourishing across borders in Southeast Asia. Read the second and third.

When Nop tried to get help from the authorities, the Chinese captors he had been sold to locked him in a dark room, beat him, and shocked him with a baton.

He had been lured to Cambodia by a promising job only to be forced into scamming Thais back home at a Chinese casino call center. But he never gave up hope.

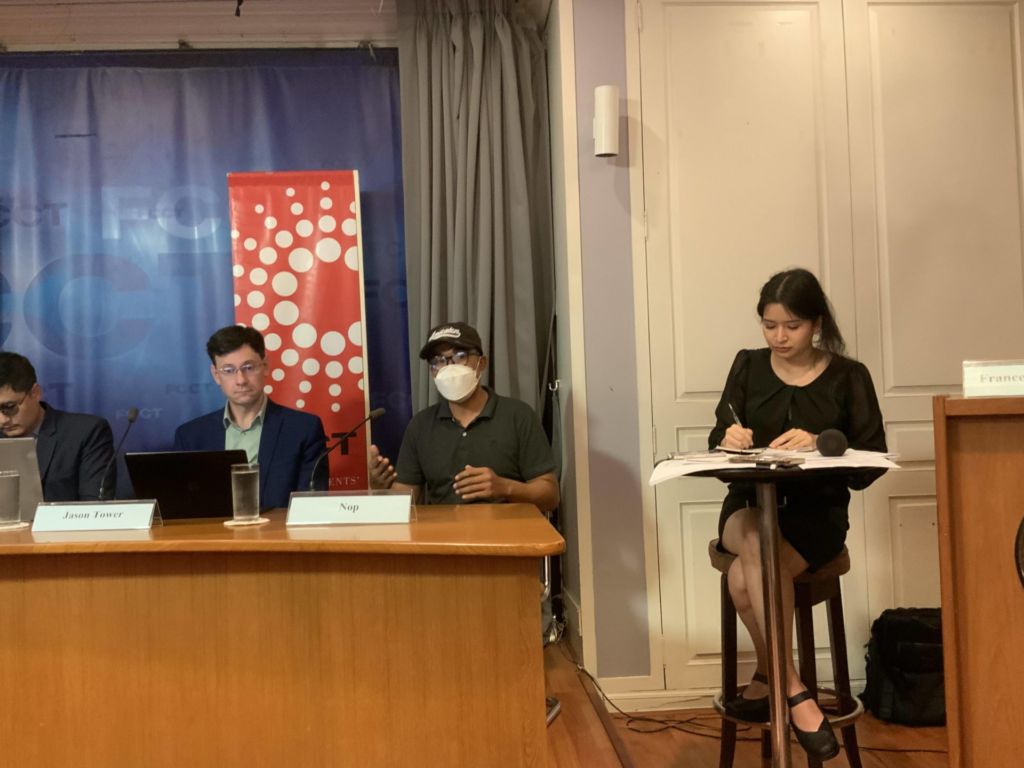

“At that time, one of the Chinese bosses found out again I was contacting people to escape out, and he put me into what I would call a dark room,” Nop said through a translator. “There, I was shocked by electric baton. I was hit on the face and back.”

Nop was one of thousands of Thais the authorities say were tricked with into virtual slavery abroad by promises of work during the pandemic. Though he was rescued in June, Nop will be in court tomorrow to prove that he was indeed a trafficking victim and not a willing participant.

Thai authorities said they rescued 1,200 Thais forced to work at Cambodian call centers in a three-month period, from November 2021 to January. Nop’s captivity ran from January through June.

Part Two: Thai man rescued from captivity abroad now faces prison at home

“The more we conduct arrests, the more offenders there will be,” said Lt. Gen. Surachet Hakphan, who serves as deputy director of the Anti-Trafficking in Persons Task Force.

Nop, 40 of Sukhothai province, was looking late last year for a good job when he saw a Facebook post about working in the office of a casino in Cambodia promising a monthly salary of US$1,000 along with free food and accommodation.

Jaruwat Jinmonca, cofounder of the Immanuel Foundation, a Lutheran group that aids trafficked people, said such ads have been effective in fooling people with promises of better lives.

‘tricked’

After arriving in Cambodia in January with his niece and her Malaysian boyfriend, Nop was picked up by a Chinese businessman and taken to Sihanoukville, a seaside town where powerful Chinese residents have close ties with the authorities – and organized crime is said to be flourishing.

He said the unnamed Chinese man and a Thai employee took him to one of the casinos that opened in recent years just in time to see Chinese visitors – and money – vanish with COVID-19.

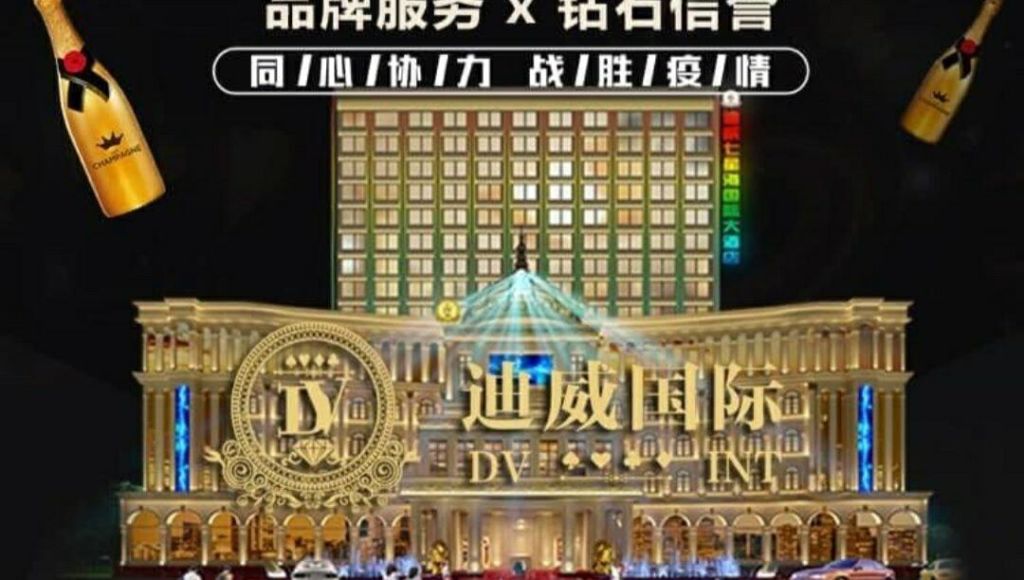

“They brought me to DV Casino, and then they took me to the fourth floor,” said Nop, whose full name was not disclosed. “As soon as I got to the fourth floor, they locked the room immediately. That was when I figured out that I had been tricked.”

They took away his phone and all of his documents, and he soon understood that his job was to “cheat and trick people.”

“They said if I wanted to go home, I would have to pay approximately 120,000 to 130,000 baht,” Nop added.

They started training Nop to conduct scam operations, and every move he made was monitored by security cameras.

Part Three: Traffickers escape justice over borders as victims go punished at home

Nop said he lived in constant fear, as a month into his new life, he saw another Thai man physically attacked and sold to another place after he attempted to contact his family.

After one month, Nop was paid a little under half the promised salary – US$450. Nop and his niece were determined to find help and get back to Thailand. That’s the first time they were punished.

“One day, a Chinese boss who was working there found out that I had informed the authorities and, also during that time, my niece’s boyfriend was sold to an area located in Chinatown,” Nop said. “And after that, my niece and I were transferred to a casino called Jing Cheng.”

The Jing Cheng, or Beijing Seaview Hotel, had just recently been opened. When China severely limited the ability of its citizens to travel during the pandemic, it cut Sihanoukville and its growing number of casinos and hotels off from their main source of income.

From the Jing Cheng, Nop was sold to another Chinese-operated scam center. But not before the “Chinese businessman” assaulted Nop with the baton in the dark room.

He didn’t get any food for three days, after which he was sold to a place called the Chon Chav International Hotel.

Luckily for Nop, the Chinese hotel manager allowed him to contact his family at night, from 9pm to 11pm. That’s when he reached out to Jaruwat of the Immanuel Foundation and the Thai police, who used fake Facebook profiles to communicate with him incognito.

“I continued to work in order to survive. At that time, I was always separated from my niece because she was staying at another place,” he said.

Bordering inhumanity

Lt. Gen. Surachet, speaking at the correspondents’ club, said the scam industry has mushroomed at an exponential rate.

“In the past, one person could trick one person,” he said. “Now, with social media, one person can trick 100 people … due to the advancement of the technology.”

While the national police force has moved to increase enforcement and rescue Thai nationals from Cambodia – where they are held against their will alongside Taiwanese, Malaysian, Chinese, and other victims – the U.S. State Department downgraded Thailand in last year’s human trafficking report.

Six years after it was removed from that report’s Tier 3 list of the worst offenders in recognition of the ruling junta’s efforts to combat trafficking, it remains in Tier 2, sometimes dropping back down to the Tier 2 “watch list.”

“We will focus on bringing victims of human trafficking home to Thailand as soon as possible and for foreign victims also return to their home countries as soon as possible,” Surachet said.

But cross-border cooperation is a hurdle to rescuing the approximately 3,000 Thais that Surachet said remain stuck in Cambodia. One of the many conditions limiting what the Thai police can do during rescue operations, he added, is being barred from talking to other Thais at the location.

Surachet, something of a celebrity in the ranks who in 2019 helped a Saudi woman fleeing her family at Suvarnabhumi Airport, said that he broke that rule when he saw the number of Thais at one location. To be permitted home, they were required to raise their hands.

“So I told those Thai people, ‘If you don’t go home, you will never be able to go back. Because I am the last officer who will be here, and no one will come again.’ After I said that, all 30 Thais raised their hands to indicate that they wanted to return home.”

Incensed, the Chinese demanded THB50,000 per person. When he refused to pay on the spot, Surachet said that he threatened to make it “a big story all around the world,” after which their unnamed boss relented and released all the Thais.

Human rights advocate Phil Robertson said the governments of Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar – where many scam operators have moved following crackdowns in Cambodia – are responsible for allowing human bondage to flourish within their borders.

“The core element is the political will to address this issue rather than having ongoing impunity, corruption, and looking on the other way that we have seen from those three governments all along,” said Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division.

Nop now lives back home in Sukhothai, but his ordeal isn’t over. Those Thais who have been tricked into participating in criminal activities have to prove in court that they were victims and not willing accomplices.

Jaruwat, who established his foundation two years ago in Chiang Mai with a disillusioned former police lieutenant-colonel, said they continue to assist victims to prove their innocence.

“We gather evidence through social media, for instance, the chat history which shows … that they were trapped, they couldn’t go anywhere while they were staying there, and this can be used as the evidence for the court,” he said.